The Flip Side of History

Winter 2004, Vol. 36, No. 4

By Lee Ann Potter

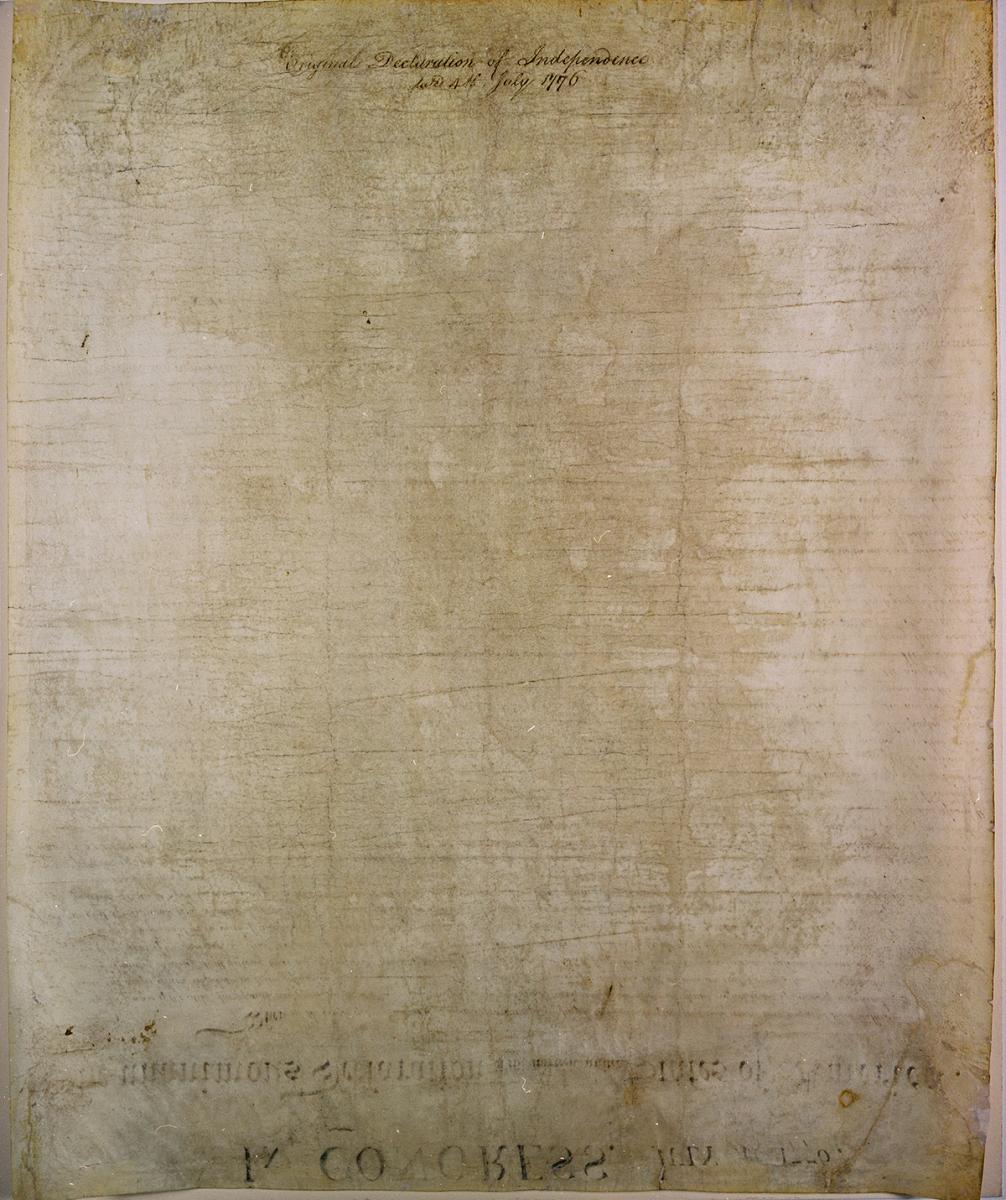

In case you were wondering, there is writing on the back of the original, signed Declaration of Independence. But it is not invisible, nor does it include a map, as the recently released Disney feature film, National Treasure, suggests. The writing on the back reads

Original Declaration of Independence

dated 4th July 1776

and it appears on the bottom of the document, upside down. While no one knows for certain who wrote it, it is known that early in its life, the large parchment document (it measures 29 ¾ inches by 24½ inches) was rolled up for storage. So, it is likely that the notation was added simply as a label.

The Declaration moved from city to city with Congress during the Revolutionary War. In 1789, it was officially transferred to the custody of the secretary of state, then it moved with the capital of the country, first from New York to Philadelphia, then in 1800 to the District of Columbia.

As this little-known information about the Declaration suggests, the backside of a historical document can reveal interesting details about the document’s history as an artifact. The details might relate directly to the document’s travels, its owners, or handlers, or they might offer clues to the economic, social, or political conditions at the time of the document’s creation.

Eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century letters, for example, were folded and sealed shut with sealing wax because envelopes had not been invented. The address was typically written in the center of the last page of a folded folio so it could be seen when sealed shut. The address can often provide insight into information not necessarily contained in the text of the letter.

For example, the backsides of many of the letters submitted to Congress by the various states transmitting their Electoral College vote counts for the 1840 presidential election read simply “To the President of the Senate of the United States/Washington City.” This small amount of information serves as a reminder of the requirements of Article II, section 1, of the U.S. Constitution—that electoral vote counts be submitted to the President of the Senate.

Another interesting example is the letter sent by Thomas Jefferson in February of 1790 to George Washington accepting the appointment to become the first secretary of state. The backside of the letter is addressed to simply “George Washington/President of the/United States.” It was stamped in black ink “RICHMOND, Feb 18/FREE.”

In addition, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century government documents were trifolded, and often their backsides contained endorsements that revealed who received the document, when it was received, and often a brief synopsis or comment—much like a routing and transmittal slip used today.

The after-action report on the Battle of Gettysburg that Robert E. Lee submitted to the Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon is one example. Considered by many historians as a turning point in the Civil War, the battle, fought from July 1 to July 3, 1863, was a major defeat for the Confederacy and for General Lee in his second invasion of the North.

The backside of Lee’s report includes, among other notations, a message from Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, indicating that he had read the document “with satisfaction” on August 5, 1863. Other nineteenth-century examples include thousands of petitions and memorials submitted to Congress that were trifolded and annotated with the date received and committee of referral.

Also, at times when paper was in short supply, information was frequently recorded on both sides of a page or written on the back of a page used for an earlier, unrelated purpose.

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, for example, was originally written on two folios that were folded into four sheets. The sheets were at some point separated, and the text appears on the first three sheets of paper—pages one and two are back to back, pages three and four are back to back, page five is a single sheet with no writing on its back, and the last sheet is blank on both sides.

Lincoln had worked on the Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863, for six months. It declared slaves in the states “then . . . in rebellion against the United States” to be free and announced that black men would be accepted into the Union armed forces.

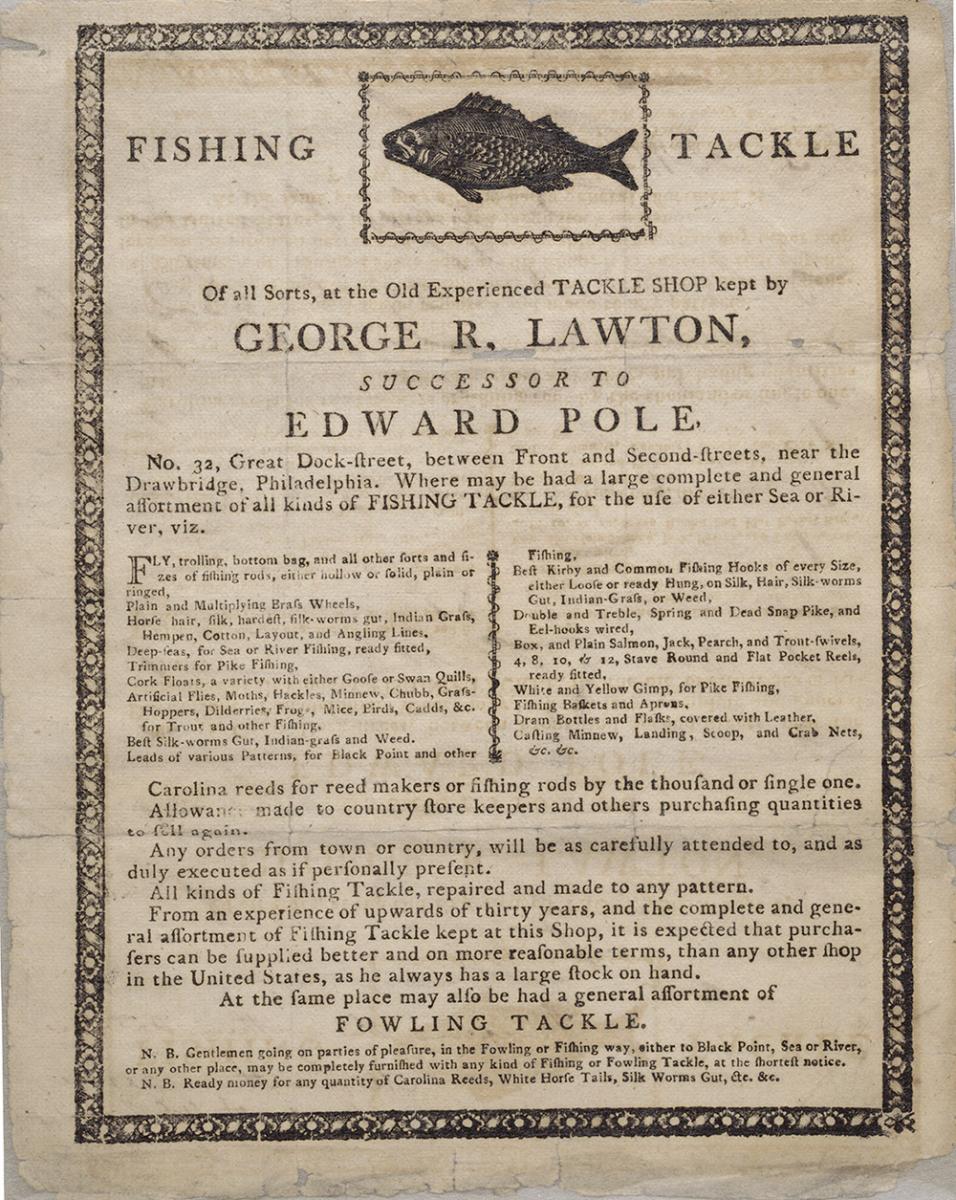

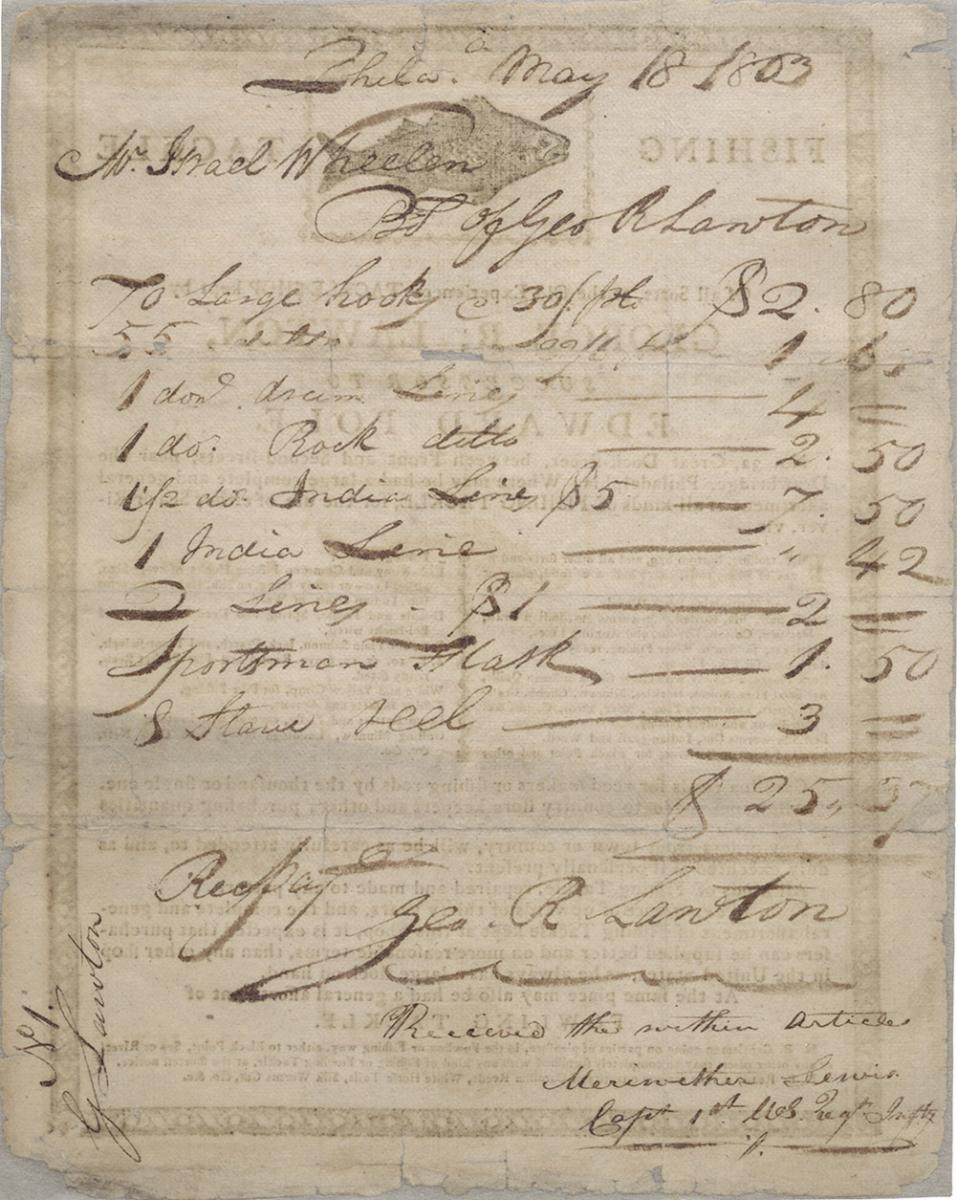

An earlier example is a bill presented to the government by George R. Lawton, an auctioneer from Philadelphia, for supplies used by the Lewis and Clark expedition, dated May 18, 1803. The document lists various articles of fishing tackle that were received by Meriwether Lewis and is written on the back of a printed broadside.

Lewis spent weeks in the spring of 1803 assembling the supplies and materials he would need for the historic expedition across the Louisiana Territory, which began May 14, 1804, and lasted for two and a half years.

Another Civil War–era document in the holdings of the National Archives that has an interesting backside is a flag design for the Confederacy that was submitted for consideration on the back of a sheet of wallpaper.

Sometimes notations on the back of a document acted as certifications or were necessary to fulfill the obligations of the front of the document. The back of an enrolled act or resolution of Congress contains the attestation phrase, “I certify that this Act originated in the Senate [or House of Representatives],” and is signed by either the chamber’s clerk or secretary.

And the back of a check or Treasury warrant can include an endorsement in the form of a signature. The back of the Treasury warrant for the purchase of Alaska, for example, was signed by Russia’s minister to the United States, Edouard de Stoeckl in August 1868. By endorsing it, he allowed for the transfer of $7.2 million dollars from the U.S. Treasury to Russia and the transfer of Alaska to the United States.

Finally, the information contained on the back of a historical document can serve as a reminder that the value of a historical document is not just in its obvious content but also in its obscure content and its physical form—that the unexpected notations and material prompt questions and generate interest that can lead to exciting historical research and a deeper understanding of the past.

Note on Sources

All of the examples cited in this article are in the holdings of the National Archives and Records Administration. The Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the public laws are in Record Group 11, General Records of the United States; the Electoral College transmittal letters are in Record Group 46, Records of the United States Senate; Jefferson’s letter comes from Record Group 59, General Records of the Department of State; Robert E. Lee’s report is in Record Group 109, War Department Collection of Confederate Records; the Lawton receipt is in Record Group 92, Records of the Office of Quartermaster General; and the Alaska Treasury warrant is in Record Group 217, Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury.

Lee Ann Potter is the head of Education and Volunteer Programs at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.