Behind the Scenes with NARA's Exhibits Staff

Winter 2004, Vol. 36, No. 4 | Spotlight on NARA

The opening in November of the Public Vaults component of the National Archives Experience marked the completion of one of the most important assignments ever given to a small group of National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) employees.

For the exhibits staff, the Public Vaults was the culmination of nearly four years of work: developing a concept; finding the documents or other records, such as film and videotape; writing scripts and labels; working with contractors to design the space and create interactive technology; and, finally, installing the "vaults."

"Building the Public Vaults was the biggest challenge we've ever faced, " said Chris Rudy Smith, head of exhibits. Although the Public Vaults have elements of a traditional exhibit, she said, "for the first time, we included lots of audiovisual materials, we developed mechanical interactives, and we considered the best ways to use computer interactives."

As a result, the Public Vaults, located just behind the Rotunda in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., are a sharp departure from the many exhibits the staff has prepared over the years for audiences in Washington and in cities around the country.

The Public Vaults give the visitor the feeling of going into the vaults and stacks of the National Archives to allow visitors to interact with records through new user-friendly high technology.

"We wanted visitors to begin to understand why records matter," said Marvin Pinkert, director of museum programs. "Our strategy was to give them the type of 'close encounter' with the process of discovery that genealogists, historians, and filmmakers experience in the National Archives research rooms every day."

Pinkert attributes the success of the Public Vaults to the diverse skill base of his colleagues: "I feel particularly pleased to have inherited such a talented core team. When I walked into this project with a science museum background, I think it caused more than a little apprehension about what was ahead. I hope that the final product represents, among other things, the way in which we learned from each other and blended our strengths."

The exhibits staff is very conscious of the special privilege its members enjoy—coming into direct contact with the documents and other artifacts that were created by some of the great names in American history.

"Even after all these years on the exhibits staff, I still feel thrilled to see an original document that was signed by George Washington or Abraham Lincoln or to work with a record that changed the course of history," Smith said. "These documents allow us to feel a direct connection to the past."

But many of the documents from NARA's holdings that go on display are not from famous figures and didn't start out historic.

Darlene McClurkin, the exhibits support specialist, said it is "certainly a thrill" to deal with those famous records, but it's also fun dealing with documents that had such inauspicious beginnings, such as "documents created by not-so-prominent persons," including the children's letters to Presidents that will be featured in the Public Vaults exhibit. "Our handwritten records have a more intimate feel about them—especially in this age of word processing," she added.

The Public Vaults is not the only project that has kept the exhibits staff engaged in recent years. They have helped to strengthen the attraction of the National Archives as not only the home of the Charters of Freedom—the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights—but as a museum destination with such notable exhibits as "American Originals" and "Picturing the Century."

Traveling versions of "American Originals" and "Picturing the Century" also brought National Archives records to visitors to host institutions around the country for visitors who may never visit Washington, D.C. Exhibit catalogs also sold well. And those exhibits, and many others, are preserved now in the online Exhibit Hall at the National Archives web site at www.archives.gov/exhibit-hall/.

An exhibit at the National Archives is not the work of one individual, but a team of individuals—a curator, a registrar, and a designer—each with a role in creating an exhibit that features records from the National Archives' holdings. Through the exhibit text and design, the staff helps visitors better understand the significance of the items on display.

The Public Vaults permanent exhibit took nearly four years to develop, but smaller exhibits can take as little as three months. Most exhibits take from one to two years from conception to opening.

For curators, it means time searching for ideas for exhibits.

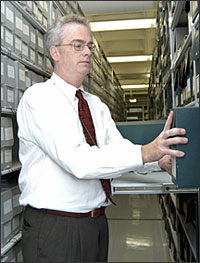

"I work every day in what historians would consider heaven," said curator Bruce Bustard, himself a historian. "To be able to do research in the stacks is thrilling. I also find that conceptualizing an exhibit—coming up with the themes for an exhibit and making the selections—is, for me, a very creative activity."

Bustard was the curator for the popular "Picturing the Century" exhibit during the late 1990s, which portrayed the first century ever photographed from beginning to end.

Will Sandoval, a curator who joined the staff in 2003, finds the job of learning new things about U.S. history rewarding. "I might go from a headstone application for a Native American to an audio recording of Kennedy during the missile crisis to a law passed by Congress," he said. "Each record requires research to fully understand the context and then try to convey this to the visitor."

Stacey Bredhoff, senior curator, who worked on the "American Originals" exhibit as well as the "New World is At Hand" exhibit in the Rotunda, said that it's a "very powerful feeling" to have close contact with documents created or signed by great historical figures.

"It's almost a spiritual experience, as though there's something in the spirit of the creators of the document that comes through," she said. "It's not something you become immune to."

Putting together an exhibit for the National Archives, Bredhoff said, "is basically storytelling . . . and they're good stories."

While researching an exhibit, the team works closely with the NARA staff archivist most familiar with records that will be needed for the exhibit, Smith said. The archivist will often suggest the most appropriate documents to use as well as help provide context for them. Later, the archivist will review the exhibit text.

For audio and motion picture records, such as films and videotapes and sound recordings, Tom Nastick, audiovisual specialist, does the searches. "The most interesting part of my job is going on 'fishing expeditions,'" Nastick said. Working with McClurkin, he has done that a lot to come up with the many videos and computer interactives for the Public Vaults. After he's found the right films to use, he moves to "the editing process, finding just the right excerpt or combination of excerpts to produce a coherent, interesting video or audio piece." Also on the team for each exhibit is a registrar, and James Zeender and Karen Hibbit play that role.

Their job is to safeguard the documents or artifacts taken from NARA facilities, which might be in Washington, at one of the regional archives, or in one of the presidential libraries, and prepare the records for display.

The first stop for exhibit documents is NARA's Document Conservation Laboratory, where any needed repairs or conservation treatment are given to the documents and artifacts. Conservators also prescribe the kind of environment and light the documents must be displayed in; in most cases, that means using only subdued lighting or possibly showing the document for only a limited time. That's the case with the Emancipation Proclamation, which can only be displayed for less than a week each year.

After conservation work, the materials go to the photography laboratory, where high-resolution photographs are taken and high-resolution scans made not only for the permanent record but also for use in NARA publications and online exhibits.

Sometimes, providing documents for exhibits is a real challenge, said Zeender, as it was with the two-hundredth anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase in 2003, when NARA had to respond to a half-dozen loan requests for the treaty without endangering the originals.

"At the same time, we were featuring the treaty in the 'American Originals' traveling exhibit," Zeender said. "Fortunately, NARA's holdings gave me a helping hand. There are three sets of the treaty in NARA's holdings, and each set consists of three documents. . . . We carefully parceled out select pages from the various documents and satisfied all concerned."

When NARA's documents travel, they are often accompanied by a NARA staff member who makes sure they travel and arrive safely, are displayed properly, and receive adequate security in the host institution. During the past three years, Hibbit has often been the courier for documents being loaned for exhibit and also traveled with the "American Originals" exhibit throughout the country. "To bring a piece of the Archives to people who can't see it every day is really exciting," she said.

After the curator finishes the research and selects the items for display, the materials go to the designer, who creates the physical presentation of the exhibit. The gallery is decided upon early in the process, but at this stage the designer works closely with the curator and registrar to decide how the documents and artifacts are to be displayed and what the labels will say.

"I enjoy the creative challenge of the exhibit design process," said Michael Jackson, one of the staff's two designers. "Working with original documents . . . can be exciting and very special. There have been moments when I have felt a very unique and exciting 'connection' to the place and time of the origination of the document, as well as to the creators of a document."

Ray Ruskin, also a designer, notes that their job is "the creative process, using exhibit themes to create physical spaces, graphic designs, colors, lighting, and casework . . . and problem-solving, coming up with practical approaches to building exhibits."

Designers must develop a display design that takes into account the number of documents or artifacts to be exhibited, the types of records and the best ways to mount them, the space available, the visitor pathways through the exhibit, and the graphics and the lighting. Again working with the curator and registrar, the designers install the exhibit. Occasionally for major traveling exhibits like "American Originals," they also go on the road to set up at each location.

Smith notes that putting on an exhibit requires teamwork not just on her staff, but agency-wide, "including archivists, conservators, the photo and digital lab staff and editors. . . . We are also very careful to have our selections and text scrutinized by experts inside and outside of the agency."

Once the exhibit is designed and opened, the curator's job is not over. He or she also speaks to the press about the exhibit as well as gives lectures to audiences about the exhibit. Bredhoff and Bustard also prepared exhibit catalogs for "American Originals" and "Picturing the Century, " respectively.

What does it take to do these jobs?

"Without discounting the role of professional training and experience, many of these jobs are fundamentally about problem-solving, innovation, flexibility, and determination, " said Pinkert. "But most of all it's about 'passion'—a love of the task of connecting with visitors. That makes the exhibit staff tick."