The Fast Mail

A Typical Day as Train No. 8 Speeds Eastward

Fall 2005, Vol. 37, No. 3

A trip on the Santa Fe Railroad's "fast mail" train No. 8, between Los Angeles and Chicago, during the first decade after World War II, would begin with the arrival of a crew of 10 to 11 clerks.

They would be assigned to a 60-foot railway post office (RPO), the largest type of distribution car, which with four storage cars made up the complement of mail equipment used on Train No. 8.

The railway post office car assigned to No. 8 had arrived in Los Angeles from Chicago the night before on train No. 7. After unloading, the RPO car was moved and spotted at Los Angeles' Union Station several hours before No. 8's departure time of 11:30 p.m.

Depending on the type of work to be handled, the crew would report to the car between 8:30 and departure time. Early arriving crew members were assigned to set up racks for mail pouches and sacks; assist with the unloading of mail pouches, which arrived by truck from the terminal post office; and case letters.

Voluminous mail that came to train No. 8 by truck at Los Angeles had already been separated in the terminal post office into pouches and sacks for the various types of cars on the train. Two of the storage cars were loaded with sacks and pouches going beyond Winslow, Arizona, and were not opened until the train reached that point. The other two storage cars remained open for taking on and putting off mail at various stations along the line. A pair of Santa Fe employees, one mail piler and his helper, rode the storage cars, and in route took in additional sacks and pouches, which were filled by the RPO clerks as the train rolled along.

Sacks and pouches of mail that were taken into the RPO car at Los Angeles and other stops, or by mail catcher at non-stop points, were opened by the clerks, who sorted the contents into other sacks and pouches for varying destinations.

For example, three of the clerks in the car handled principally pouches of first-class mail, one clerk handled newspapers, another had charge of registered mail, and one handled mixed mail. Of the remaining five clerks, one handled mail for Illinois, another distributed mail for Colorado and New Mexico, another was in charge of mail for California and Arizona, another worked Oklahoma mail, and the eleventh clerk handled Texas.

From the time the crew reported to the train in Los Angeles to their arrival the next morning in Ash Fork, Arizona (485 miles away), the clerks on No. 8 worked through the night at breakneck pace in order to keep up with the seemingly endless flow of mail.

Long-distance crews such as those on No. 8 and trains like it worked on 28-day cycles in a given month in which they worked 6 days on and had 8 days off, with at least three roundtrips in each month. Former clerks speak of the goal to get the job done that the crews had, regardless of the amount of mail, even though the work required long hours of standing in a noisy dusty environment on a moving mail car.

Before closing out their trip, the original crew members each made out a memorandum to the clerk in charge, detailing the amount of distribution performed on the trip and any irregularities noted for mail handled in route. The clerk in charge of the crew then prepared a trip report based on information supplied by the crew and forwarded that report to the chief clerk of the district.

The report served multiple purposes for the service. It was a record of the type of work done by each man on the crew and it was a time and pay record from which the monthly payroll was prepared.

Dog-tired, the crew detrained at Ash Fork for a well-deserved rest. The second of four new crews needed to work the mail on into Chicago took over.

Return to The "Fast Mail": A History of the U.S. Railway Mail Service, Part 1 | Part 2

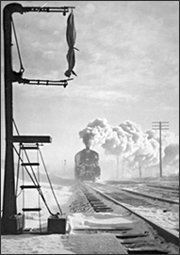

To pick up mail in communities not scheduled for stops, clerks on mail trains used a special catcher arm to retrieve pouches of mail suspended along the track. (28-M-C-1)

To pick up mail in communities not scheduled for stops, clerks on mail trains used a special catcher arm to retrieve pouches of mail suspended along the track. (28-M-C-1)