Rich, Famous, and Questionably Sane

When a Wealthy Heir’s Family Sought Help from a Hospital for the Insane

Summer 2007, Vol. 39, No. 2

By Miriam Kleiman

Katharine Dexter McCormick was sure of what was causing her husband's mental instability.

After all, she knew something of the subject she was talking about. At a time when few women went to college, she was the second woman to attend one of America's citadels of learning, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the first woman to graduate with a degree in science, majoring in biology.

And she came from a distinguished and learned family. Her great grandfather, Samuel Dexter, had served in the cabinets of both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson; her grandfather was one of the founders of the University of Michigan; and her father was a distinguished attorney. Before her marriage, Katharine had planned to go to medical school.

Her husband, Stanley, was from an even more prominent family—the McCormicks of Chicago. Stanley McCormick's father, Cyrus, had in 1834 patented the mechanical reaper, then built up the family business with his brothers. Stanley himself, as comptroller of the company, had helped in the merger with other manufacturers to form International Harvester.

Other branches of the McCormick family have played major roles in the history and development of Chicago. They founded and operated the investment firm William Blair & Co. and published and edited the legendary Chicago Tribune. Today, the name McCormick is not an unfamiliar name for buildings and other public facilities and many philanthropic causes in the Chicago area.

But in the early 1900s, Stanley McCormick was ailing, and Katharine eventually became convinced that it was due to a hormonal imbalance, or a defective adrenal gland. But the doctors did not agree with her, and records in the National Archives detail the decades they spent fighting her and trying to diagnose and treat Stanley's condition, without much progress, through psychotherapy.

The records about Stanley McCormick are from St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., which until 1987 was a federal facility. Today, it is owned by the government of the District of Columbia and is best known as the home of John W. Hinckley, Jr., who was convicted by reason of insanity for the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan in March 1981.

Founded in 1855 as the Government Hospital for the Insane, the hospital's mission, as defined by mental health reformer and founder Dorothea Dix, was to provide "humane care" and "enlightened curative treatment" for "the insane of the Army, Navy, and District of Columbia." During the Civil War, when it served as a hospital for wounded soldiers, the soldiers did not want to say they were in an insane asylum, and instead said they were at St. Elizabeths, the colonial name for the land where the hospital is located, overlooking the point where the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers meet. Congress officially changed the name in 1916. At its height in the 1940s, the complex covered over 300 acres and housed 7,000 patients.

Dr. William Alanson White was superintendent of St. Elizabeths from 1903 until his death in 1937. His tenure there coincided with a 34-year time span that provided a historic and unprecedented transition in the understanding and treatment of mental illness.

Dr. White helped introduce Freudian psychoanalysis, or "talk therapy," in the United States and embraced it as a theory and treatment method. He converted St. Elizabeths from a prison-like setting in which physical restraints and sedatives were used to control its patients to one that resembled a college campus—complete with classes, a beauty parlor, gardens, and recreational activities.

Four boxes of Dr. White's files deal with the case of Stanley McCormick, and they document a family's decades-long monumental struggle over power, money, guardianship, sex, and Freud.

Officially Dr. White served as a paid consultant on the case for more than a decade. However, these files show he played a more complex and varied role—acting as family confidant, adviser and mediator as this near-epic battle played out in the courts and the press.

As the youngest son of Cyrus McCormick, Stanley had graduated with highest honors from Princeton, where he was a football star and champion tennis player. He attended Northwestern law school, then became comptroller of the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, where he helped in the formation of International Harvester—a company worth over $20 million by 1920.

While Stanley showed signs of mental instability before their marriage in 1904, Katharine attributed this largely to Stanley's controlling family and especially to his mother, Nettie. Katharine hoped that removing Stanley from his family in Chicago would be beneficial, and the newlyweds moved to Boston.

By 1906, Stanley's episodes had increased to the extent that he was hospitalized at McLean Hospital for the Insane in suburban Boston. At age 32, Stanley was diagnosed with "dementia praecox of the catatonic type," or schizophrenia, characterized by marked violent outbursts and gradual mental deterioration, punctuated by periods of relative clarity. His intake report noted a family history of mental illness: "All the family of nervous temperament, mother eccentric, sister insane." The same report noted that Stanley was fed eggnog, malted milk, and oyster stew.

Stanley's family hoped that personal, intense care and a warmer climate would help him. In June 1908, he was moved—along with a team of doctors and aides—to "Riven Rock," the McCormick family estate in Santa Barbara, California. The property at Riven Rock had been purchased in 1897, and an estate was built for Stanley's older sister Mary Virginia, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 19. Ironically, Stanley had supervised the Riven Rock groundbreaking and the mansion's construction. Mary Virginia had since been moved to a sanatorium in Huntsville, Alabama.

In 1909, Stanley was declared legally incompetent, and a judge appointed Katharine and Stanley's siblings Anita and Harold to serve as the "Personal Care Board" to direct and oversee his treatment.

Given Stanley's discomfort, anxiety, and anger around women, his treatment team restricted all visits and contact with women, including Stanley's mother, sisters, and wife. Katharine followed this "rigid rule of exclusion" but would visit Riven Rock and observe Stanley from afar. Over the next 20 years, Stanley's condition worsened, but his doctors continually resisted Katharine's efforts to bring in other consultants and try new therapeutic approaches.

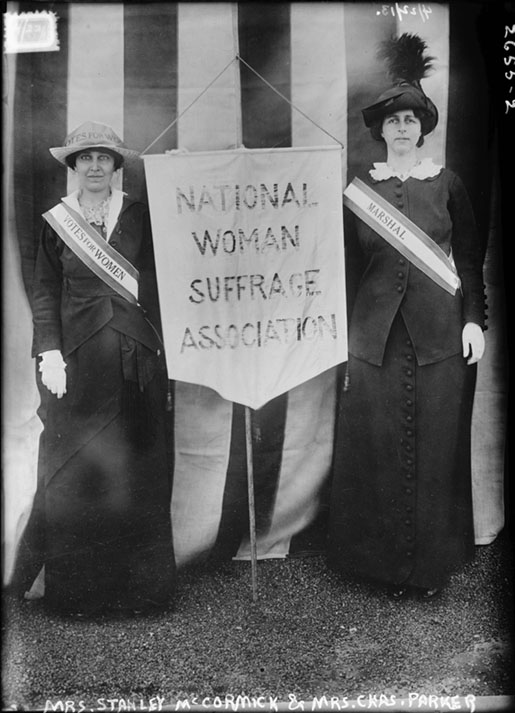

While she had little say over her husband's care at the time, Katharine fought for a voice on other issues. She joined the woman suffrage movement—providing funding, organizing protests, and speaking at rallies and protests. She became vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Following the ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920, she served as the first vice president of the League of Women Voters.

She also was active in the reproductive rights movement. She heard Margaret Sanger speak in 1917 and grew convinced that women could only fully control their lives if they could control if and when they chose to bear children. Having succeeded on the woman suffrage front, Katharine redirected her financial contributions and personal advocacy to the cause of birth control, even smuggling in diaphragms from Europe to New York at Sanger's request.

Katharine had a sophisticated understanding of biology and devoured medical journals, seeking alternative physiological causes and potential cures for Stanley's condition. She applied her MIT degree to exploring the then-new field of endocrinology. Katharine grew convinced that a hormonal imbalance—a defective adrenal gland—had caused Stanley's illness.

She began to organize and fund mental health research in this field—establishing a Neuro-Endocrine Research Foundation at Harvard Medical School in 1927. Originally called the "Stanley R. McCormick Memorial Foundation for Neuro-Endocrine Research Corporation," it was the first such U.S. research institute to explore the link between endocrinology and mental illness. Katharine also created a research center for the care of the mentally ill at Worcester State Hospital.

Through her extensive and broad research, Katharine learned about the then-new field of Freudian psychology and prevailed upon Stanley's family to change his treatment. Sigmund Freud had visited the United States in 1909, when he was practically unknown, but his popularity grew. Katharine believed his approach might also be effective with Stanley, in addition to potential endocrine treatment.

She later explained her openness to new approaches:

As new vistas of hope open that may possibly promise relief to Stanley and older methods continue to fail, I shall naturally change my point of view. How can I do otherwise? How can I remain inactive so long as there is any possibility of anything constructive being done to help him. If any new form of treatment appears I shall advocate its trial.

Katharine sought experts in the mental health field who embraced this new "talk therapy" and contacted Dr. White in March 1927. Largely due to Katharine's influence, the Personal Care Board "decided to change, in great measure, the character and kind of medical treatment" for Stanley. Katharine asked Dr. White to take over Stanley's care. Unwilling to leave St. Elizabeths, Dr. White offered to serve as senior consultant on the case, and recommended she contact New York psychiatrist Dr. Edward J. Kempf, who had worked as a psychiatrist at St. Elizabeths from 1914 to 1920.

Stanley's Personal Care Board signed a one-year contract stipulating that Drs. White and Kempf would bear equal responsibility for Stanley's care, and that all resources of modern medicine should be at their disposal. Dr. Kempf would move to Riven Rock to treat Stanley. Dr. White would collaborate with Dr. Kempf and make personal visits to California as needed. Dr. White would be paid a retainer of $500 a month ($5,900 in today's inflation-adjusted dollars), plus expenses and extras as travel and work required, including $5,000 ($59,000 today) per visit to Riven Rock. Dr. Kempf would receive the unprecedented sum of $10,000 ($118,000 today) a month for his therapeutic services. The family also paid $12,500 ($147,500 today) for care and maintenance of Riven Rock, plus fees for additional consultants, physicians, and aides.

Dr. White's files contain copies of Stanley's medical reports, court filings, letters from Katharine, Anita, Harold, Stanley, and Dr. Kempf, as well as copies of much of their correspondence with one another. Also included in the files are two Easter cards from Stanley.

Psychoanalysis

Dr. Kempf believed that close family ties would advance the therapeutic process. For the first time in two decades, Stanley was allowed to see women, and Katharine began regular visits. Under Dr. Kempf's care, Stanley—now age 53—began intensive Freudian psychoanalysis two hours daily. Kempf later described this treatment to the Personal Care Board:

Most of his [Stanley's] odd mannerisms have been traced to their origins in childhood experiences, such as putting hands in the toilet, way of drying himself until he "chafed", using soap excessively, foot fetich [sic], ritual with pajamas, carrying his felt slippers as if they were live pets. . . . A group of gravely tragic childhood experiences has been partly analyzed which has given material for many of his strange mannerisms and beliefs. These analytical discoveries of repressed psychic traumas have made it far easier to communicate with Mr. McCormick about his rituals and compulsions while he is in the act.

Dr. Kempf wrote Dr. White of other issues the two discussed but that Dr. Kempf had chosen not to share with the Personal Care Board: "We have worked out further the serious episode of his childhood over the accidental death of a pet which I thought best to leave out of the report."

Endocrinology vs. Psychology

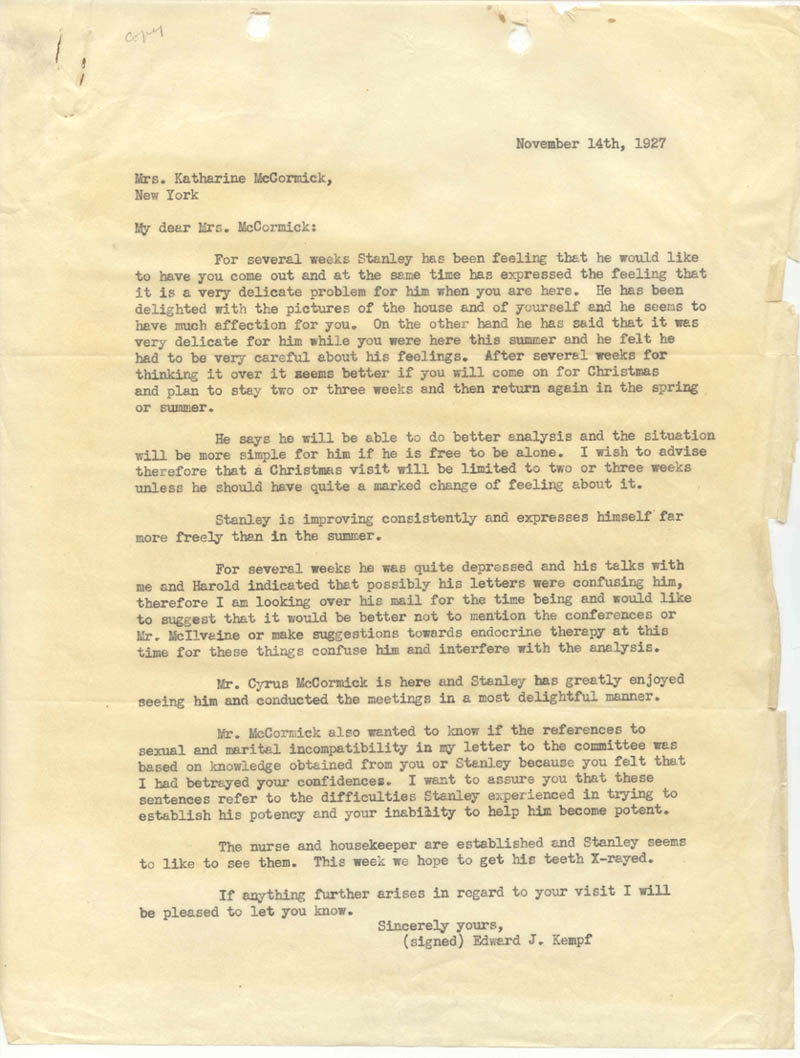

Katharine expected Drs. Kempf and White to advance Stanley's treatment on both the psychological and physiological fronts. Once established at Riven Rock, Dr. Kempf told Katharine that there would be no endocrine testing until Stanley's psychoanalysis was completed. Dr. Kempf urged Katharine not to discuss endocrine therapy with Stanley "for these things confuse him and interfere with the analysis."

Dr. White had been open to the possibility of physiological testing and endocrine treatments. Responding to Stanley's brother's assertion in a letter that mental illness was "merely the effect of past experiences," Dr. White responded that "such a point of view in its ignorance of physiological cause and effect is as fanatical as that of the Christian Science healer." However, Dr. Kempf wrote Dr. White that "endocrine studies of Stanley would be made more to relieve Mrs. McCormick than Stanley" and dismissed her appeal for testing as merely "a sentimental cry."

Katharine reminded Dr. Kempf that she had selected him, and there had been an understanding:

I ultimately selected Dr. White and yourself to attend to this aspect of the case. But before either Dr. White or you came under consideration I had become aware that in all probability another aspect of the case would have to be dealt with, for I had it on good authority from both psychologists and physiologists that there was some physiological or glandular background to such mental conditions as that from which Stanley suffers. . . .

[You] both assured me that you were aware of the possibility of an endocrine factor in such cases as Stanley's . . . so I did not anticipate that you would not be willing to have both the psychological and endocrinological treatment applied to the case.

Stanley's "talk therapy" continued indefinitely, with few tangible signs of improvement. Kempf wanted to return to New York and suggested that an estate for Stanley be built alongside his own home. Katharine objected to the seeming permanence of this situation and the direction and delay of the treatment.

Dr. Kempf blamed Katharine for impeding his work with Stanley, later writing to White that "Stanley was improving marvelously until Mrs. McCormick came out" [to visit]. Dr. Kempf suggested that Katharine not visit Stanley because "he says he will be able to do better analysis and the situation will be more simple for him if he is free to be alone." He also wrote he was screening her letters to her husband.

Katharine wrote Dr. Kempf that such censorship was unacceptable: For twenty years through misplaced confidence and overpersuasion, I allowed stupid people to dam and divert that current of understanding, which even in Stanley's ill condition, could have passed between us.

If you reflect for a moment on the fact that you are now working with Stanley because I was aware of the possible value of analysis, and because I selected you, you will realize that it is not in any way my intention to interfere with the analysis or to spoil your work. I have followed your advice in the past and I welcome it in the future. I do, however, intend to see that you conserve your proper function.

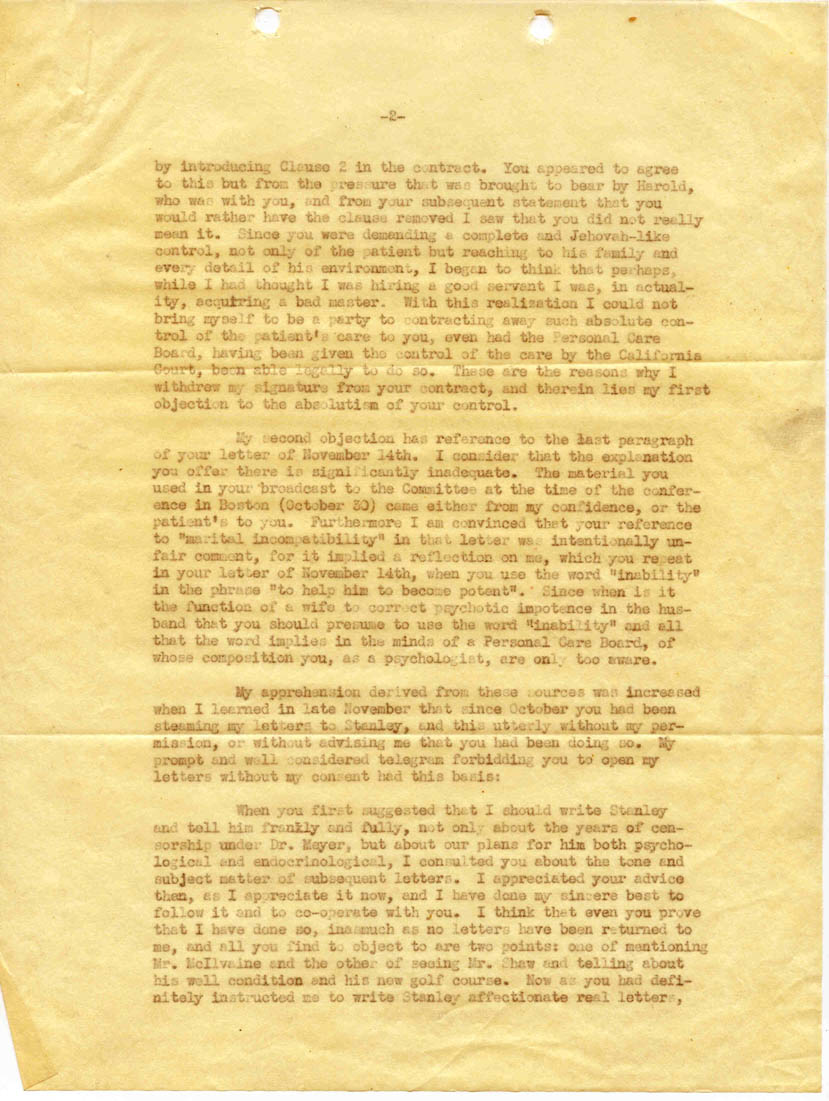

The conflict escalated, and Katharine told Dr. Kempf that his contract would not be renewed "since you were demanding a complete and Jehovah-like control, not only of the patient but reaching to his family and every detail of his environment." She wrote: "I had thought I was hiring a good servant I was, in actuality, acquiring a bad master."

However, Stanley's siblings secretly had extended the contract. New agreement in hand, Dr. Kempf rejected endocrine treatment for Stanley and barred Katharine from visiting Riven Rock. He then tossed out the trump card—writing (and copying Dr. White and the Personal Care Board) about "the difficulties Stanley experienced in trying to establish his potency and your inability to help him become potent [emphasis added]." He concluded that she and Stanley were incompatible, and he recommended divorce.

Katharine immediately rejected Kempf's findings on her marriage and relations thereof:

[Your] reference to "marital incompatibility" . . . was intentionally unfair comment, for it implied a reflection on me, which you repeat . . . when you use the word "inability" in the phrase "to help him become potent." Since when is it the function of a wife to correct psychotic impotence in the husband that you should presume to use the word "inability" and all that the word implies in the minds of a Personal Care Board, of whose composition you, as a psychologist, are only too aware.

Dr. Kempf complained to Dr. White of Katharine's "determination to have her way" and called her "impulsive, unheeding and dominating." He wrote that the conflict had escalated:

Since I have dared to say that one of the factors in Stanley's psychopathology is marital incompatibility and since I refused to let Mrs. McCormick bring in her battalion of endocrinologists, she has been making a wild effort to break up the analysis. Her attitude to the situation is a very transparent one. . . . It is obvious that she cannot endure seeing Stanley get well through an analysis because of her own feelings about the causes of his illness.

Dr. Kempf reported to the Personal Care Board that Stanley's ongoing mental illness was due to Katharine's strong personality and her emasculation of him, explaining his need to venture into such territory "because of the manner in which the marital relations have had a profound bearing on the patient's psychopathology":

At times he [Stanley] refers to Mrs. McCormick affectionately and at others he becomes severely resentful for past failures and incompatibilities. . . . His emotional conflict of love and hate, involving his marriage, is still very pathological and beyond his control. . . . This must be regarded as dangerous for himself because of the possibility of maniacal excitement or depression which may be precipitated by too close relations with his wife except under the most delicately controlled circumstances.

[T]here are profound constitutional incompatibilities between himself and his wife, which dispose towards severe conflict of feelings and psychopathic distortions of the personality of the weaker individual in the married union.

Mr. McCormick is constitutionally submissive, masochistic and tender minded, and unable to express himself potently in the face of dominating, aggressive characters in the wife's personality. These dilemmas attain great severity and cause profound introversion of the personality, mental suffering, brooding, self pity, sexual impotence and despair, with increased tendency towards homosexuality and homosexual panics.

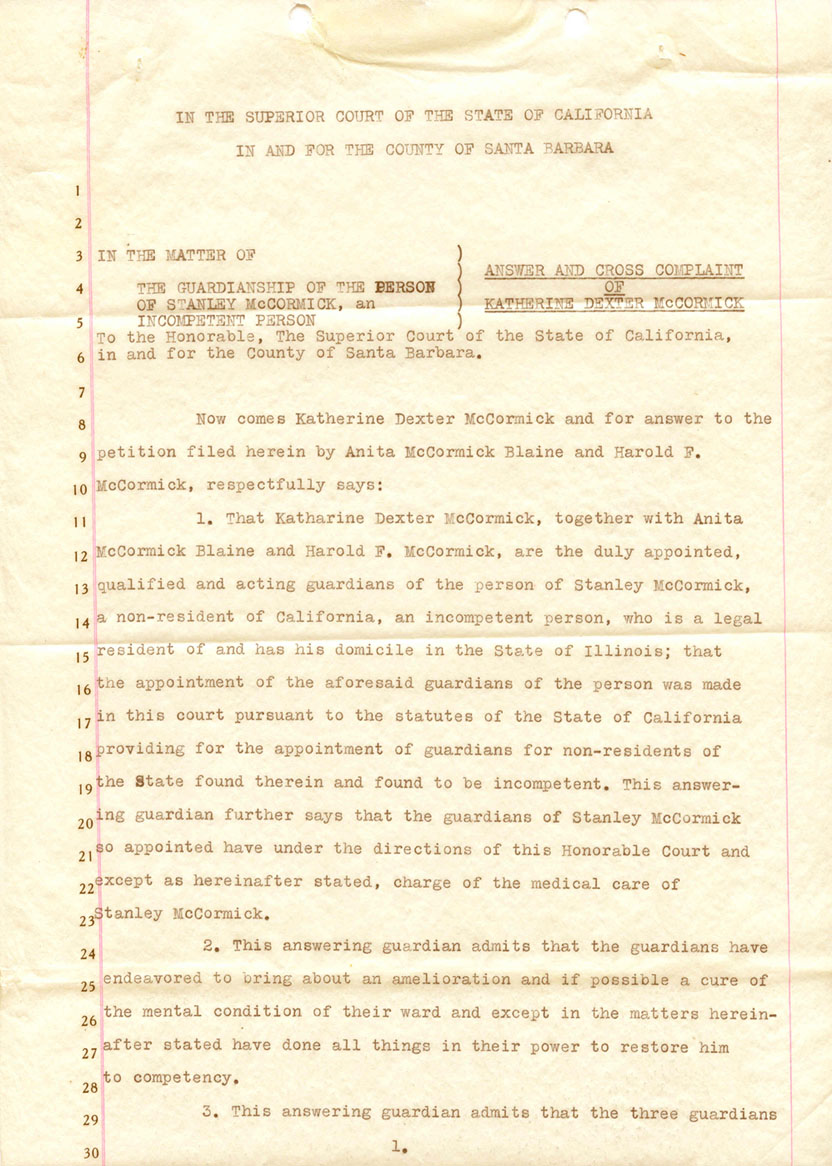

Psychoanalysis on Trial

Understandably outraged, Katharine petitioned the court for sole guardianship over Stanley in 1928. She hired as her attorney Newton Baker, co-founder of the Baker, Hostetler, Sidlo & Patterson law firm and former secretary of war during World War I, under President Wilson. The lawsuit contended that Kempf's treatment had harmed Stanley, that Kempf had rejected alternative approaches and was trying to alienate Stanley from his wife. Katharine was unhappy with Dr. White, as well, deeming him an absentee consultant; she told the court that he had visited Riven Rock just twice and had made only a single recommendation in his role as consultant—that his contract be renewed.

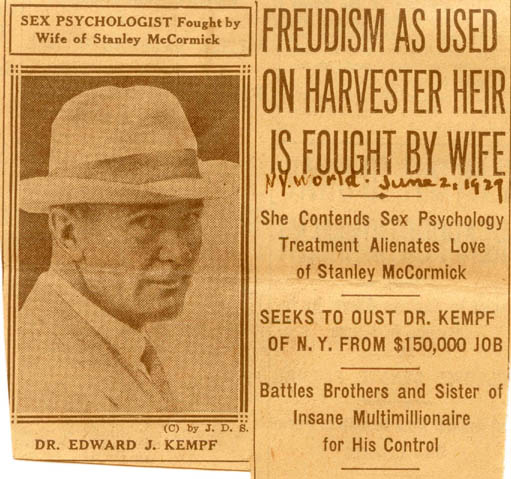

Dr. White's folders include numerous faded, brittle scraps of yellowed newsprint about the trial the press labeled "the Freudian equivalent of the Scopes trial." Articles shared new terminology with the public decades before such words as "transference" and "analysis" became sitcom fodder. National coverage of the dramatic, high-stakes trial even eclipsed the stock market crash. The New York Times called the trial "the largest custody case in the history of the country." Sensationalist headlines splashed the following:

"Freudism Faces Fade-Out as Wife of Mad Millionaire Fights Psycho-Analyst for Maniac Husband's Love and Guardianship!"

"She Contends Sex Psychology Treatment Alienates Love of Stanley McCormick"

"Battles Brothers and Sister of Insane Multimillionaire for His Control"

"Sex Psychologist Fought by Wife of Stanley McCormick"

"Hot McCormick Fight Forecast"

Reporters seized on Katharine's accounts of illness and excess:

The story which she has brought into court is of Arabian Nights quality, a weird dream of doctors' bills, psychological theory and fabulous luxury. Over all hangs the tragic misfortune of insanity. . . . He has his own orchestra, a motion picture theatre, a small army of servants and Dr. Kempf.

Kempf expected an easy win, writing Dr. White that "every point in her charges can be very well answered and most of them will . . . put her in an unfavorable light as a difficult, interfering person." However, he warned that Katharine might raise the case of "Mr. Shaw," a mental patient at McLean hospital who had allegedly improved as a result of endocrine therapy. Dr. Kempf thought Mr. Shaw's marital incompatibility could have been a factor, and asked Dr. White to "get the straight story of Shaw's married life" given Dr. Kempf's belief that "the death of his wife was related to his recovery."

The trial did not proceed as Kempf had hoped. Dr. White's attorney, Oscar Lawler, urged White to testify at the California trial because the judge "has developed a vigorous antipathy to Kempf," objecting "not to psychoanalysis but to that as administered by Kempf." White said he could not leave Washington when his "appropriations bills [were] still pending before Congress." Dr. White eventually did testify and received $10,000 ($120,000 today) in payment for doing so.

Katharine won the court fight to have Drs. Kempf and White ousted—the court ordered their contract to end on March 15, 1930. Dr. Kempf graciously offered to continue his services until new care was found, stating "it would be a great tragedy to deprive this patient of further psychoanalysis." In his last report to the Personal Care Board, Dr. Kempf thanked Stanley's siblings for their support and blasted Katharine for obstructing and impeding Stanley's treatment.

Katharine was not named sole guardian, however. Instead, the court expanded Stanley's Personal Care Board to include the deans of the UCLA and Stanford medical schools (in addition to Harold, Anita, and Katharine). Each doctor received $15,000 annually ($184,447 today) for their role on the Board. Kempf continued to consult with Stanley's siblings, working with Anita and Harold "trying to explain to them their own psychology in relation to Stanley." Anita retained Dr. White as her personal consultant, and records include a payment for his services plus a financial "token of appreciation."

Two years after the trial, with little progress and fear that Stanley would "rot away in seclusion," Katharine asked the court to allow him to be moved from Riven Rock to a center for treatment of the mentally ill. The fees paid to the medical school deans on the Personal Care Board were "grossly wasted" she wrote, given that no new treatments were tried and not even "a valid basal metabolic rate" for Stanley had been determined. She explained it was in the doctors' financial interest for Stanley's treatments to continue indefinitely, given that the experts "receive for their not very time-consuming services fees which in all probability are larger than their salaries as deans of their respective medical schools."

Katharine noted the irony of some state patients at Worcester State Hospital (where she funded mental health research and care) receiving better care than Stanley:

[T]he veriest pauper coming to the Research Service of this Hospital [Worcester] is infinitely better studied, more intensively investigated and in short greatly better cared from than is Stanley McCormick. . . . It was the recognition of this fact which drove me to ask your court to give me sole control of his care.

When Stanley died in 1947 at age 73, Katharine, as his sole beneficiary, inherited an estate estimated worth almost $40 million ($472 million today). Once Stanley's estate was settled, Katharine redirected her attention and philanthropy to reproductive health issues. She had stayed in contact with Margaret Sanger, who introduced her to Gregory Pincus and his pioneering research on fertilization and hormones.

Katharine funneled to Dr. Pincus more than $2 million ($23 million today), nearly all of the money used to support his lab's research and development of the contraceptive pill, first licensed in 1960. Ironically, the woman blamed for Stanley McCormick's inability to consummate his own marriage became the catalyst for the sexual revolution.

And just a few years after Stanley's death, research psychiatrists conclusively linked schizophrenia to a chemical imbalance, as the young Katharine had insisted many years before.

Read excerpts of three other cases from Dr. White's files.

Miriam Kleiman is a public affairs specialist with the National Archives and Records Administration. She has written previously in Prologue about her search for people whose stories are preserved in the National Archives Public Vaults exhibition (Fall 2005). She first came to the NARA in 1996 as a researcher to investigate lost Jewish assets in Swiss banks during World War II. She joined the agency in 2000 as an archives specialist and is a graduate of the University of Michigan.

Note on Sources

Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital, Record Group (RG) 418, at the National Archives holds 428 cubic feet of textual records spanning St. Elizabeths history as a federal institution—from the first patient logbooks in 1855 to its transfer to the Government of the District of Columbia in 1987.

Entry 36 holds the records of Superintendent William Alanson White. This collection includes six boxes labeled "Personal correspondence, Records pertaining to consultations and requests for medical advice, 1906–37." Files relating to Stanley McCormick fill the first four boxes. Box six holds files of additional consultations, listed in alphabetical order, including those relating to Edward Beal McLean, Henry and Anne Suydam, and Thalia Massie.

Secondary sources consulted for this article include two autobiographical works by William A. White and one by Evalyn Walsh McLean:

William Alonson White: The Autobiography of a Purpose (New York, Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1937)

Forty Years of Psychiatry by William A. White, A.M., M.D., Sc.D. (Nervous and Mental Diseases Publishing Company, New York and Washington, 1933).

Evalyn Walsh McLean, Queen of Diamonds: The Fabled Legacy of Evalyn Walsh McLean (Hillsboro Press; Commemorative edition, 2000).

Background information on Katharine Dexter McCormick is from Katharine Dexter McCormick: Pioneer for Women's Rights by Armond Fields (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003).