“Sweltering with Treason”

The Civil War Trials of William Matthew Merrick

Summer 2007, Vol. 39, No. 2

By Jonathan W. White

© 2007 by Jonathan W. White

The American Civil War was not just a conflict between North and South. Indeed, many smaller conflicts pervaded both sections of the divided nation. In the South, for example, Jefferson Davis had to deal with noncompliant and obstructive governors in North Carolina and Georgia. In the North, Abraham Lincoln encountered many Southern-sympathizing holdovers from previous presidential administrations.

Democrats had controlled the presidency for most of the antebellum period, and for many years Northern Democrats had been the strongest allies of the Southern slaveholding class. Consequently, many federal posts—including the life-tenured seats in the federal judiciary—were held by Democrats of questionable loyalty. Upon coming to power in 1861, President Lincoln and the Republican majority in Congress had to determine what to do with federal officers whose loyalty to the government was doubtful. One of the most controversial of these instances arose about a little-known federal judge in Washington, D.C.

The U.S. Constitution gives federal judges life tenure—they "shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office." The Constitution makes no provision for the reduction or withholding of a judge's salary, but he "shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors."

Congress and the executive branch have not always found it practical to impeach a sitting federal judge, and in several instances have found novel ways to rid the judiciary of a nuisance on the bench. Before Thomas Jefferson took office as President, the Federalist Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1801, which created 16 new judgeships for the Federalist President, John Adams, to fill. In 1802, after the Jeffersonian takeover of Congress, the Judiciary Act of 1801 was repealed, removing the recent Federalist appointees from office, and a new act was passed, giving the privilege of filling the courts to President Jefferson.

During the Civil War one federal judge, West Hughes Humphreys of Tennessee, was impeached for becoming a district judge in the Confederate judicial system without ever resigning his federal commission. The impeachment and conviction of Judge Humphreys was an easy case, for his complicity in the rebel war effort was beyond doubt. Other instances arose, however, in which the actual or perceived disloyalty of a federal judge was not so easily dealt with.

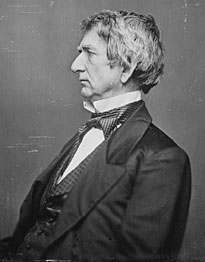

The most prominent case was that of William Matthew Merrick, a 43-year-old judge on the federal circuit court in the District of Columbia. Merrick had been placed on the bench by President Franklin Pierce in 1855. Although a Democrat, Merrick came from Whig ancestry—his father, William Duhurst Merrick, had served in the U.S. Senate as a Whig from 1838 to 1845. Merrick's wife, however, came from a Kentucky family with many rebel ties.

From the beginning of the war, Merrick was suspected of disloyalty. An anonymous letter, sent to Gen. Winfield Scott in January 1861, implied that Merrick hoped to see Washington overrun by secessionists. Later that spring, he allegedly refused to administer the oath of office to one of Lincoln's appointees to the Treasury Department, telling the civil servant, "I consider a man holding your political opinions, as being unfit to hold any office, and I will not be a party to qualify you to do so." Many newspapers referred to him as having sympathy for the rebellion, and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles noted that "the hearts and sympathies of the present judges [of Merrick's court] are with the Rebels."

In the early months of the war, Merrick made a name for himself by issuing writs of habeas corpus demanding that underage boys who had enlisted in the Union army be sent home. Lawyers in the nation's capital who sought these writs, according to one newspaper account, "seemed to have a willing assistant in Judge Merrick, who readily granted orders, citations, and the thousand and one processes by which lawyers obtain fees and annoy people." According to district court records at the National Archives, Merrick issued about 20 of these writs in the late summer and autumn of 1861. Merrick was faithful to the law—for it was illegal to enlist a minor without a parent's consent—but his actions were an embarrassment to the Lincoln administration and an administrative aggravation to the army. With each writ Merrick ordered a military commander to appear before his bench with "the body" of the soldier to explain why the soldier was being kept in the military.

Arguments by military commanders do not appear to have convinced the judge. Merrick ignored several high-ranking officers who claimed that the boys were old enough to serve, and he even called in one brigadier general on contempt for ignoring the writs he had issued. In this instance the general ignored Merrick's first writ because the secretary of war had ordered him to do so; only after Merrick issued a second writ and an order to bring the general in for contempt of court did the general release the soldier and issue a statement "that he [the general] has not as he conceives defied the authority of your Hon. Court—that it never was his intention to treat with disrespect your Honor nor the authority of your Hon[or]'s Court—that he has acted in strict conformity with the law of the land and literally obeyed the order of his superior officers." In issuing these orders Merrick adamantly upheld the rule of civil authorities over the military; his actions were a bold statement that he would not submit his court to overreaching executive authority.

Few of these habeas cases caught the attention of the press until the Lincoln administration decided to take action against the judge. On October 21, 1861, Secretary of State William H. Seward directed Brig. Gen. Andrew Porter, the provost marshal in Washington, "to establish a strict military guard over the residence of William M. Merrick." Porter asked whether "the judge should be confined to his house," but Seward replied that house arrest was not necessary: "Indeed it may be sufficient to make him understand that at a juncture like this when the public enemy is as it were at the gates of the capital the public safety is deemed to require that his correspondence and proceedings should be observed." That same day, in plain violation of the Constitution, President Lincoln ordered that Merrick's pay be suspended.

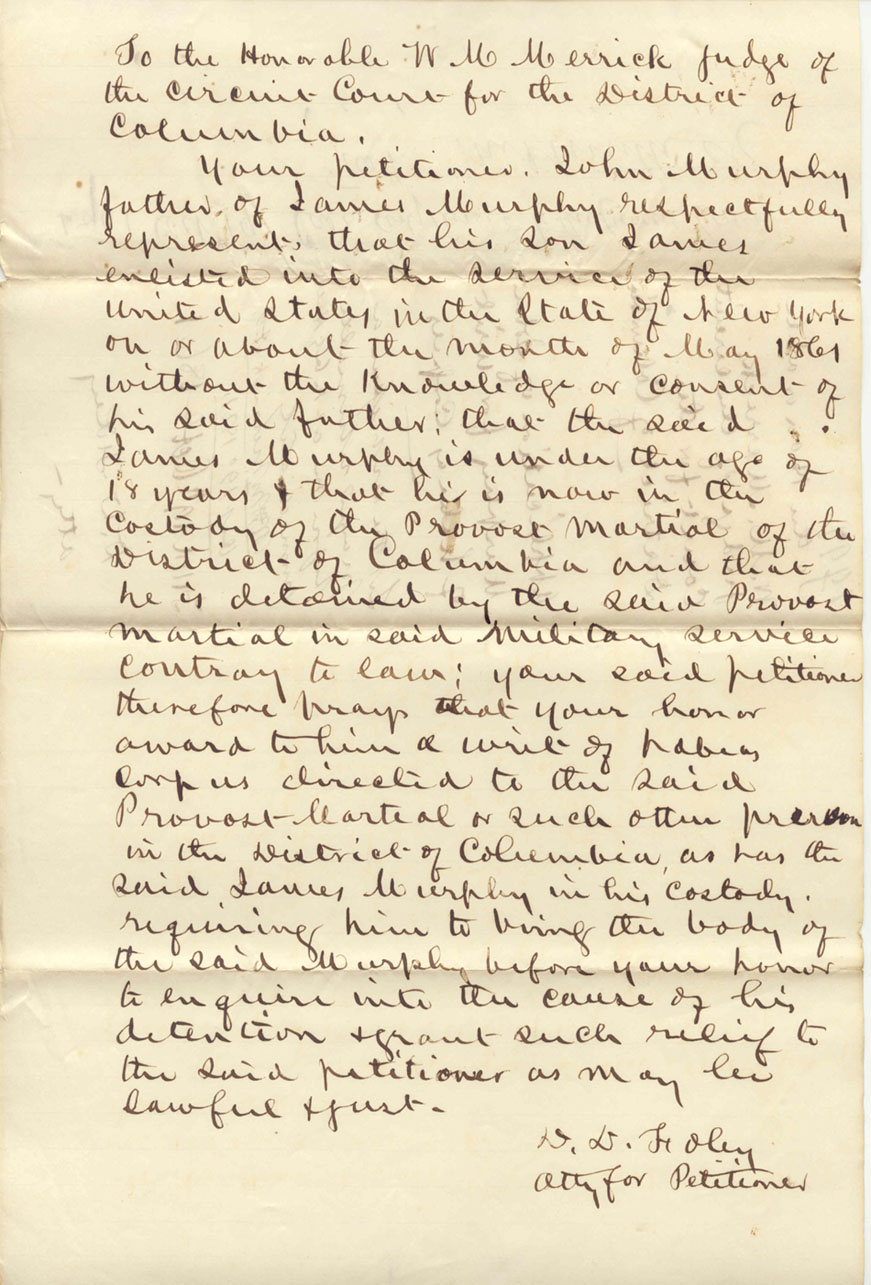

The habeas case that brought such a forceful response from the executive branch had to do with a 17-year-old boy, James Murphy, who had enlisted in the 12th New York Volunteer Infantry. James's father, John Murphy, demanded a writ be issued as his son was underage and had enlisted without his parents' consent. Moreover, contended the father, his "son is now anxious to return [home] & your Petitioner is desirous of having him discharged from" his military unit. Murphy quickly procured a lawyer, D. D. Foley of Washington, who petitioned Judge Merrick for the writ.

Judge Merrick issued the writ to Foley, who then took the unusual step of personally delivering it to General Porter. Under normal circumstances a writ would be delivered by the deputy marshal of the District, but it being a Saturday that the writ was issued, and "by reason of the many engagements of the Deputy Marshal," Foley opted to deliver the writ himself. General Porter was so incensed at Foley's action that he had the lawyer arrested. On Monday, Porter placed the armed guard outside of Merrick's residence, at 425 F Street, which Merrick discovered when he returned home from dinner with his fellow judges sometime between 7 and 8 p.m. "I learned that this guard had been placed at my door as early as 5 O clock," wrote the judge.

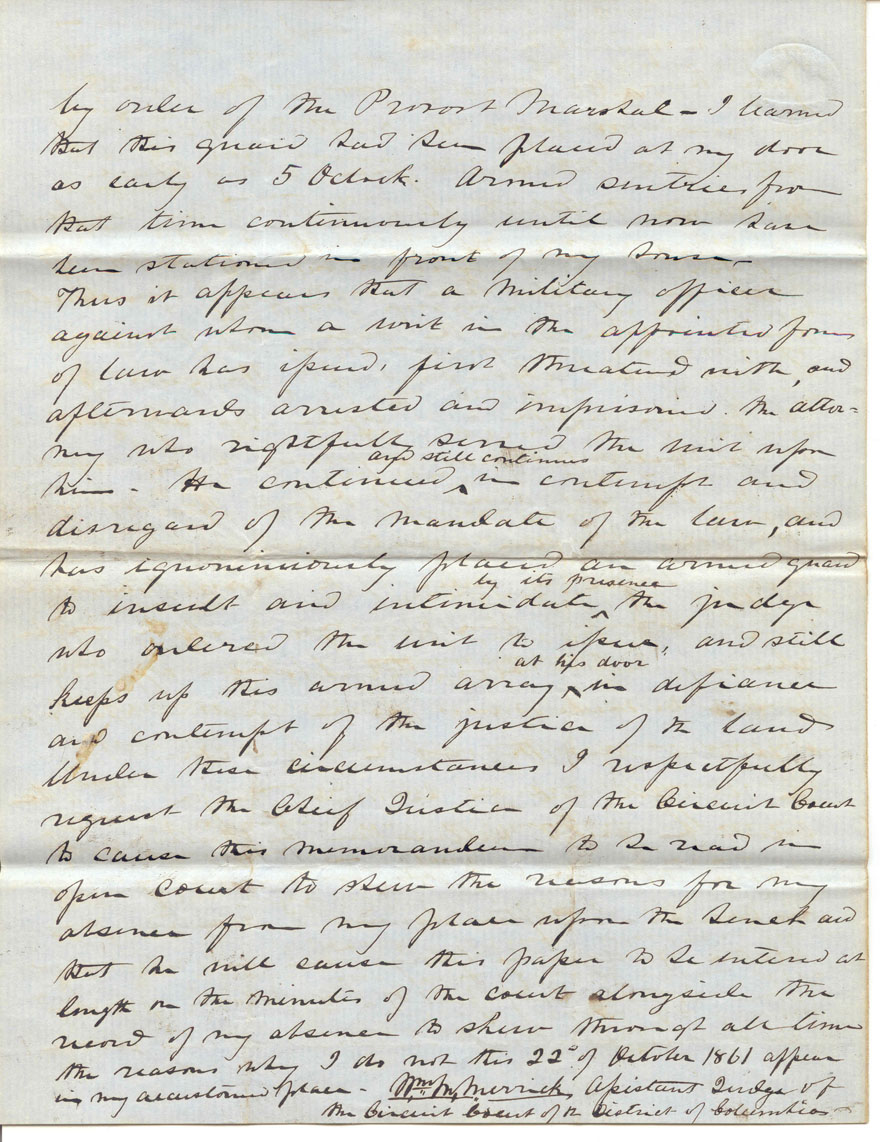

Armed sentries from that time continuously until now have been stationed in front of my house. Thus it appears that a military officer against whom a writ in the appointed form of law has issued, first threatened with, and afterwards arrested and imprisoned the attorney who rightfully served the writ upon him. He continued and still continues in contempt and disregard of the mandate of the law, and has ignominiously placed an armed guard to insult and intimidate by its presence the judge who ordered the writ to issue, and still keeps up this armed array at his door in defiance and contempt of the justice of the land.

While Seward had not intended to have the judge confined to his home, but only kept under strict surveillance, Merrick considered himself under house arrest, and the Chicago Tribune, a Republican paper, called him "a prisoner." Subsequently, Merrick sent a letter to the two other judges on the circuit court, informing them why he was unable to attend the session. The two other judges—James Sewall Morsell and James Dunlop—protested that General Porter had obstructed the process of the law, and Morsell declared that "this was a palpable and gross obstruction to the administration of justice, to prevent a Judge of this Court from taking his seat because he issued a writ just such as the law requires." The arrest had been made, according to Morsell, only "for the purpose of embarrassing him in this particular subject, and to prevent his appearance in Court."

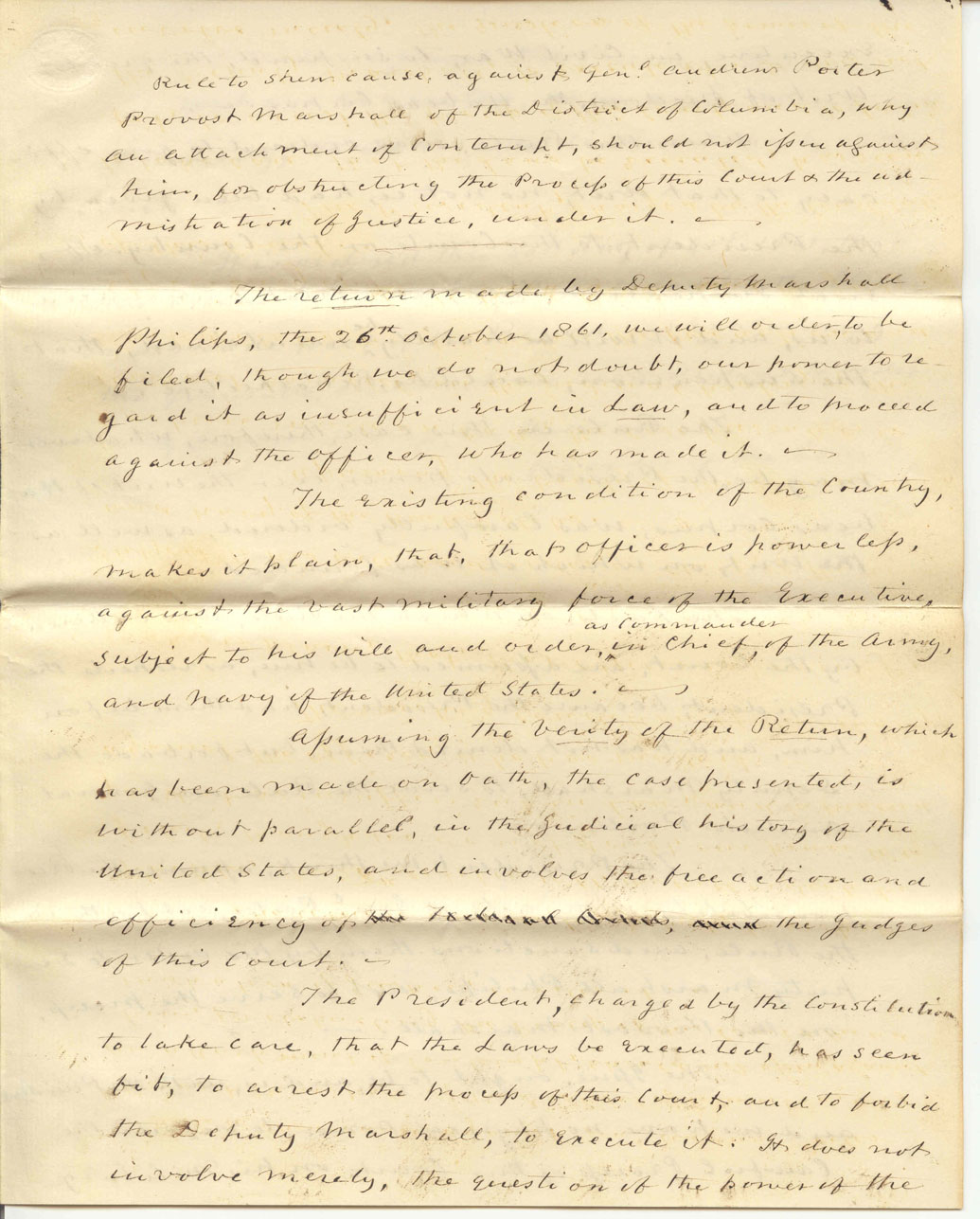

In truth, an air of confusion pervaded wartime Washington, as Lincoln had made no official proclamations regarding martial law or the suspension of habeas corpus. "What is the real state of things?" asked Judge Morsell. "If martial law is to be our guide, we look to the President of the United States to say so." The court would "not pretend to controvert the right of the President to proclaim martial law, but let him issue his proclamation." The court then ordered the deputy marshal to deliver a rule to General Porter, ordering him to appear before the court within four days to show why he should not be held in contempt.

General Porter never appeared at Washington's City Hall, where the circuit court held its sessions. Instead, on the fourth day, the district attorney appeared on behalf of the deputy marshal to explain that he had not issued the rule to General Porter "because he was ordered by the President of the United States not to serve" it, and because "the privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus has been suspended for the present by the order of the President of the United States in regard to soldiers in the Army of the United States" within the District of Columbia. The deputy marshal claimed that he did not intend to "disrespect the orders of this Hon. Court," but explained that he had to follow the orders of the President.

The court determined that it would not take any steps against the deputy marshal because, as Judge Dunlop explained, "The existing condition of the Country, makes it plain, that, that officer is powerless, against the vast military force of the Executive." Still, this case was "without parallel, in the Judicial history of the United States, and involves the free action and efficiency of the Judges of this Court." Rather than take care that the Constitution and laws of the United States be faithfully executed, the President "has seen fit, to arrest the process of this Court, and to forbid the Deputy Marshal, to execute it."

Dunlop pointed out that Lincoln had never publicly and officially suspended the writ of habeas corpus (which many believed to be a congressional and not presidential power, anyway, since the suspension clause is in Article I of the Constitution). Merrick, therefore, had lawfully issued the writ on Murphy's behalf, so the court's subsequent orders ought also to have been respected. "When this Rule, was ordered, to give efficacy to that writ, no notice, had been given by the President, to the Courts or the Country, of, such suspension, here, now first announced to us, and it will hardly be maintained, that the suspension, could be, Retrospective."

Since the provost marshal and deputy marshal were only acting under orders, the President, therefore, must assume the responsibility for their actions. "The issue, ought to, be, and is, with the President," declared Judge Dunlop, "and we have no physical Power, to enforce the lawful Process of this Court, on his military subordinates, against the President's prohibition." Having exhausted "every practical Remedy, to uphold, the Lawful authority, of this Court," Dunlop ordered that his opinion be filed in the records of the court as a statement of why no further action would be pursued.

Judge Morsell filed a separate opinion, declaring that "the Law in this Country knows no superior," that the civil authorities must be superior to military power, and that "this Court ought to be respected by every one as the Guardian of the personal liberty of the Citizen." Morsell concluded, "I therefore respectfully protest against the right claimed to interrupt the proceedings in this case." The judges, in these opinions, mounted a minor challenge to Lincoln's assertions of executive authority, but they ultimately found themselves powerless to effect any change; they subsequently backed down and moved on to other business.

It is unclear whether Judge Merrick was actually confined to his home, as he claimed, or if he stayed there as some sort of publicity stunt, knowing that his letter of protest would make it into the press. Such a strategy might have been successful. William Howard Russell, a British journalist covering Civil War Washington, remarked that Merrick was a "brave, upright, and honest judge" who did what he was "duty bound" to do in issuing the writs. When Merrick and the lawyer, Foley, were arrested, Russell proclaimed it the "heaviest blow which has yet been inflicted on the administration of justice in the United States, and that is saying a good deal at present" and he blamed Lincoln for "doing that terrible thing which is called putting his foot down on the judges." Russell also took notice of the judge's wife. "As the sharp tongues of women are very troublesome," he said, "the United States officers have quite little harems of captives, and Mrs. Merrick has just been added to the number. She is a Wickliffe of Kentucky, and has a right to martyrdom."

The Washington Evening Star, by contrast, emphatically reminded its readers that "Judge M is not under arrest, as is being alleged." Rather, he had been placed under surveillance because of his "disposition to defeat the measures for the preservation of the Union which the President has felt it to be his duty to take through his officer—the Provost Marshal."

"The President," continued the editor of the Star, "is not likely to permit his military measures to be thwarted by what he may deem legal shifts and evasions on the part of lawyers, especially if their loyalty may, in his judgment, be questionable."

Democrats were indignant about the arrests. Later during the war, William B. Reed of Philadelphia reminded Democrats of Secretary Seward's role in the affair. "It was Mr. Seward who applauded the Provost-Marshal at Washington for resisting a habeas corpus for a minor, and threatening to imprison, or, indeed, imprisoning the officer who brought it. It was Mr. Seward who placed a sentinel at Judge Merrick's door, for the double and kindred purposes of insult to him and intimidation to the electors of Maryland, and so avowed it."

Republicans, by contrast, praised the summary action of the Lincoln administration. "Troublesome Lawyers not Tolerated" ran the headline of the Chicago Tribune, while Horace Greeley's paper headlined "A Meddlesome Lawyer in a Trap." The New York Evening Post declared that if Merrick should continue to embarrass the national government, "he will be visited with punishment. The course he has already taken has fanned anew the secession flames in Washington." Accordingly, the New York Times surmised that the military had done Judge Merrick a favor by instituting the guard. "If the populace should take it into their heads that the Judge sympathized with the rebels, they might make violent demonstrations—in which case it would be convenient to have the timely interposition of the sentry."

In mid-November the guards were removed from Judge Merrick's house, and he resumed his place at the bench. But his troubles were far from over. When, in 1862, Congress enacted a federal income tax, Merrick protested that the money withheld from his income constituted a reduction in his salary in violation of Article III of the Constitution. Merrick sent a letter to Francis E. Spinner, the treasurer of the United States, explaining that it was unconstitutional to tax the salaries of federal judges. Spinner responded in a rude and unprofessional manner. In his reply Spinner enclosed a letter he had received from another federal judge who thought he had not paid his full share of the income tax and who hoped to rectify the situation. Spinner enclosed this letter to Merrick, as he later explained, "to point out to him the difference between a loyal judge and himself; and that, while I would not discuss with him the question whether Congress had, or had not, the constitutional right to tax the salaries of United States judges, I would suggest to him, that it certainly had the right to abolish his damned rebel court."

Merrick was outraged. He immediately sent Spinner's letter to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. "In response to my official communication to the Treasurer," Merrick informed Chase, "I have this day received a paper containing expressions and imputations of a character so unusual in official correspondence that I feel it to be my duty to enclose that paper for such consideration and action as the head of the Treasury Department may think the occasion requires." Chase asked Spinner to explain himself, to which Spinner replied that had he known that Chase would eventually see it, "I would have written it a damned sight stronger." The secretary then gave Spinner a stern "lecture on official etiquette, urging that the different branches of the government should act in harmony with each other, and that comity required respectful language in all communications passing between them." But finding that Spinner would acknowledge no wrongdoing, Chase concluded, in a good natured manner, "Well, General, while I feel that your letter is very pertinent to the subject, it is very impertinent to the judge."

Secretary Chase sent an apology to Merrick, explaining the necessity of the tax and that he had confronted the treasurer on the proper tone of official correspondence. But the matter was far from settled. According to Spinner, Chase gave the details of the situation to Whitelaw Reid, a Cincinnati journalist who published the story, which was then widely reprinted throughout the nation: "Members of Congress saw it, laughed at it, as a good joke: but, after a little, viewed it in another light, and came to the conclusion to carry out the joke. So a bill was introduced in Congress, and became a law, by which the then United States Court of the District of Columbia was abolished, and the judges were abolished as well."

Within a few months of the income tax episode, the Republicans in Washington had had enough, and they decided to rid themselves of Judge Merrick once and for all. They could not impeach him, for he had committed no overt act of treason, nor anything that constituted a high crime or misdemeanor.

The Republican Congress took a play from the old Federalist and Jeffersonian playbooks of 1801 and 1802—the idea that Francis Spinner had advocated in his impertinent letter to Merrick. They would abolish the court he sat on and create a new one, affording President Lincoln the opportunity to appoint a whole new slate of judges who would be more overtly sympathetic to the Union cause.

In 1863 there were two federal trial courts in the District of Columbia. The circuit court, which had been created by the Judiciary Act of 1801, had three judges—Merrick, Dunlop, and Morsell. The criminal court, which had been established in 1838, had one judge, Thomas H. Crawford. On January 23, 1863, Crawford died, after several months of ill health. Morsell had been a judge on the circuit court for nearly 50 years and was, according to many Republicans, "almost superannuated." Thus, there were only two judges left to handle the work of four. The time was ripe, they believed, for Spinner's "good joke" to be told.

The bill "remodeling the courts of the District of Columbia" was read on the Senate floor in February 1863. Debate began on the 18th, and the Senate approved it on the 20th. The Democrats could do little to stop its passage.

Democrats argued that the bill's sole purpose was to rid the D.C. courts of a disloyal judge. "And yet," declared Senator Willard Saulsbury of Delaware, "we have had no complaint, by petition, by remonstrance, or otherwise, sent to Congress against these judges." Republicans, of course, professed no desire to remove any particular judges from the bench; it just happened to be a byproduct of the bill. "I would be the last man to legislate merely for the purpose of turning a man occupying a judicial position out of his place," announced Senator Ira Harris of New York, the architect and sponsor of the bill. "I think I may disclaim any such motive on the part of the Judiciary Committee who authorized this bill to be reported."

But Democrats called their bluff. Lazarus Powell of Kentucky suggested that rather than abolish the present judgeships, additional judges be authorized to sit on this court with the old ones. "The Senator from New York, who presented this bill, . . . disclaims the intention by this bill to get rid of the present judges. The amendment I have offered will test the sincerity of the Senators on that subject." Further, Powell argued, politicizing the judiciary in this way would set a bad precedent for the future. Whenever one party gained control of the legislative and executive branches, they too would be tempted to "pass a bill baptizing the courts by some other name, and turning judges out and putting in partisan favorites." If a judge had committed an impeachable offence, the Constitution prescribed a method for his removal.

On two days' notice, Senator Garrett Davis, a Kentucky Unionist with increasingly Democratic proclivities, produced the signatures of 49 members of the D.C. bar who opposed any reorganization of the federal courts in the District. Such political tampering with the courts, Davis argued, would damage the independence of the judiciary and allow "political hacks" to infiltrate the federal bench. This bill was an "assault upon the judiciary" and a barefaced attempt "to substitute the present impracticable incumbents with supple tools who will carry the abolition dogmas into the courts of the District." Similarly, Senator Saulsbury repeated the oft-said contention: "There can be but one motive, and that is to give the present Executive of the United States the power to render the judiciary of this District subservient to his will, by such appointments as he shall choose to make. Sir, it is a dangerous precedent to set in the Senate. And can you hope it will not be followed?"

Finally, toward the end of the debate, some Republicans were willing to admit their true motives in the affair. From the beginning Senator Harris had insisted that President Lincoln could renominate any of the sitting judges if he chose. Later, Harris admitted that he preferred that judges with questionable loyalty not be renominated. Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts was more direct and to the point: "I have not, I say, the greatest faith in these courts. As to one of their judges, I mean Judge Merrick, I believe his heart is sweltering with treason. He has been under arrest since this rebellion broke out. I believe that during this session of Congress his home has been the resort where sympathizers with disloyal men have held councils, and secret councils, and I have good reason to believe this to be true." Knowing that the Republicans' motivation was in question, Wilson proposed an amendment that would add two additional judges to the bench (while keeping the present judges), but when that was voted down, he supported abolition of the circuit court. In the end, the Senate adopted the bill with the provision for abolition.

On the House side the bill met the same fate, though even more quickly. Republicans rammed the bill through the House, permitting hardly any debate. They believed reorganization of the courts had the "very desirable effect of legislating out of office one judge very old, and another very disloyal." Democrats, meanwhile, repeated the claims that the bill set an awful precedent and was unwanted by the citizens of the District of Columbia. Through parliamentary maneuvering, Democrats mounted several filibuster attempts but were ultimately unsuccessful, and the bill passed 86 to 59, the day after it was first read in the House. Former President James Buchanan privately deplored the Republican tactics: "Such acts of wanton tyranny will surely return to plague the inventors. There will be 'a tit for a tat.'"

Under the provisions of the law, the new court was called the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. When the time came for Lincoln to make his four new appointments to the supreme court, he made sure to choose wisely. Like all shrewd Presidents, he wanted nominees whom he could trust to uphold his policies and constitutional principles. A year later, when given the opportunity to replace Roger B. Taney as chief justice of the United States, Lincoln remarked, "We wish for a Chief Justice who will sustain what has been done in regard to emancipation and the legal tenders. We cannot ask a man what he will do, and if we should, and he should answer us, we should despise him for it. Therefore, we must take a man whose opinions are known." These sentiments guided his decision making in 1863 as well.

Aside from certain policy concerns, Lincoln also appears to have wanted to change the nature of the court from a local one to a national one. The judges who sat on the present circuit court were all from Washington, D.C., or Maryland (areas notorious for sympathy with secession), and local newspapers assumed that other local attorneys would be chosen to fill the new positions. Lincoln's new appointees, however, hailed from the entire United States—Ohio, Delaware, New York, and Virginia.

Lincoln's four choices were men of solid Republican standing. For chief justice he tapped David Kellogg Cartter of Ohio. A Democrat until 1856, Cartter was firmly within the Republican fold by the time of the Civil War. In 1860 he was chairman of the Ohio delegation to the Republican National Convention in Chicago and was instrumental in swinging that delegation's votes from Salmon P. Chase to Lincoln. Subsequently he was considered by many to be a strong possibility for a spot in Lincoln's cabinet. In 1880 a Washington magazine remarked, "Certainly no man ever got closer to Mr. Lincoln or was more often appealed to for consultation and advice than Judge Cartter." Cartter also showed unfailing loyalty to the Union cause. While serving as U.S. minister to Bolivia, he received word of his son's death at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Though utterly distraught, he still supported his other son joining the army in 1863.

Lincoln's other choices for the bench—George P. Fisher, Abram Baldwin Olin, and Andrew Wylie—were also qualified Republican choices. Fisher, a Unionist member of Congress from Delaware, was a firm supporter of Lincoln's plan for gradual emancipation in the border states and had voted for the bill abolishing the old circuit court and creating the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. In 1862 he failed in his reelection bid for Congress, and his term expired on March 3, 1863. Eight days later, Lincoln appointed him to the new court. Olin, a Republican congressman from New York since 1857, was a firm defender of the Lincoln administration and had been the floor manager of the conscription bill in the House.

Lastly, Wylie, a lawyer from Alexandria, Virginia, was reputed to be the only person to vote for Lincoln in Alexandria City in 1860. Prior to the election Wylie had received threats that he would be shot if he voted for Lincoln, but he braved the hazards and did so anyway. Following the election, as he sat on his front porch in Alexandria, a bullet whizzed through the air and shattered the drinking glass he held in his hand. Enough was enough already, and he decided to move into Washington. Earlier in 1863 Wylie had been tapped to serve as the judge of the criminal court in D.C., but it was abolished with the circuit court before his nomination ever went up for a vote. Upon the creation of the new supreme court, Lincoln put Wylie's name forward again. Although some Republicans in the Senate had doubts about Wylie's ability to be a good judge, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton spoke for many when he said that Wylie's "merits and qualifications & service are sufficiently known."

In selecting his nominees, Lincoln consciously turned the new D.C. court into a national tribunal. He wanted judges with national reputations and who shared his sense of the American cause, and Republicans were generally pleased with his choices. "Under the existing condition of affairs here, therefore, it is by no means strange that in making these appointments he should have sought nominees known well to the whole country having this momentous stake involved, rather than gentlemen of this community, who, however well known and confided in at home, are unknown to the country in connection with the troubles of the times," wrote the editors of the Washington Evening Star. "We sincerely believe their selection to be a subject of congratulation to this community. Some of our fellow citizens would doubtless have preferred others, on personal grounds. But personal considerations should not and could not safely be permitted to influence the President's action in such a case." Horace Greeley's Tribune noted that "the result will be the administration of justice in the District upon Anti-Slavery, instead of Pro-Slavery principles." In making his appointments, Lincoln replaced localism and perceived treason with nationalism, loyalty, and judges who understood his sense of the common good.In keeping with Congress's and Lincoln's vision for this court, the new justices placed more stringent standards to sitting at their bar than was required by federal law. In order to be admitted to the bar, lawyers had to take the "iron-clad test oath," which Congress had adopted in 1862. This oath, which was required of all federal employees and appointees, demanded affirmation of past and future loyalty. Some Democrats refused to take the oath. Upon hearing that one of his friends had refused to take it, former President James Buchanan remarked, "If he cannot conscientiously take it, there is an end of the question. If he has refused simply because the Court has no right to require it, I think he has not acted prudently." In requiring the iron-clad oath, the new judges established their court as a beacon of loyalty amid a sea of Southern sympathy—it was not until January 1865 that Congress would require the oath of all lawyers practicing before the federal bench. The court, it seems, hoped to set a new, national, standard for loyalty.

As for Judge Merrick—he put his house in the District up for rent and moved back to Maryland, where, among other things, he worked to get at least one former Confederate—Senator David Yulee of Florida—released from military prison. In the years following the war, Merrick resumed his practice as a lawyer and served as a professor of law at Columbian College (what is now the George Washington University). He also served as a delegate to the 1867 Maryland state constitutional convention; he spent one term in the Maryland legislature (1870); and he served one term in Congress, from 1871 to 1873. When he failed in his reelection bid in 1872, Merrick's career in public life appeared to be at a close.

Writing about 1884, Francis Spinner—the treasurer of the United States who had withheld Merrick's pay and who harshly chastised him for sympathizing with the rebels—recalled the "good joke" that had been had in 1863 when Congress abolished Judge Merrick's court. "The present judges have, no doubt, enjoyed the joke hugely, ever since," exclaimed a gleeful Spinner, "but, it is believed that it has never been fully appreciated by Judge Merrick."

In truth, Spinner did not yet know the real punch line. On May 1, 1885, President Grover Cleveland appointed Merrick to a seat on the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia—a seat that was vacated by Andrew Wylie, one of Merrick's original replacements. He served on that bench until his death, on February 4, 1889. Merrick, it appears, had the last laugh.

Jonathan W. White is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is editor of A Philadelphia Perspective: The Civil War Diary of Sidney George Fisher (Fordham University Press, 2007) and has published articles on Civil War politics in Civil War History, American Nineteenth Century History, and The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. His dissertation, "To Aid Their Rebel Friends," is a study of treason, loyalty, and nationalism in the North during the American Civil War.

Note on Sources

I would like to thank Herman Belz and Mark Neely for commenting on earlier drafts of this essay. I also thank Shelly Snook, Terri Santella, and Heather Bourk for help locating images of Judge Merrick.

Primary to my research for this article were records at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and College Park, Maryland. Records of District Courts of the United States, Record Group (RG) 21, which hold the records of the federal courts, provided me with both the habeas corpus records (Entry 28 [Segregated Habeas Corpus Papers, 1820–1863], microfilm publication number M434) and the records related to the surveillance of Merrick's home (Entry 2 [Minute Books, 1801–1863], microfilm publication number M1021, and Entry 6 [Case Papers, 1802–1863], civilian trial case files nos. 1097 and 1098). Correspondence between Merrick and members of the Treasury Department may be found in General Records of the Department of the Treasury, RG 56, Entry 140 (Correspondence of the Office of the Secretary of the Treasury: Letters Received from Judges, Marshals, Clerks, Attorneys, and Other Members of the Judiciary), and Entry 27 (Miscellaneous Letters Sent, K Series). Many of these documents have been reproduced in volume 2 of John A. Hayward and George C. Hazleton, eds., Reports of Cases Civil and Criminal Argued and Adjudged in the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia for the County of Washington (1895), and in volume 2 of series 2 of War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (1880–1901).

A number of manuscript collections at the Library of Congress, including the Abraham Lincoln Papers, the William H. Seward Papers, the Dunlop Family Papers, the Cartter Family Papers, and the George P. Fisher Papers, were also helpful. Debate over abolition of the circuit court and creation of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia may be found in the Congressional Globe for the third session of the 37th Congress.

Among the newspapers I consulted were the Chicago Tribune, New York Daily Tribune, New York World, Washington National Intelligencer, Washington National Republican, New York Times, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, New York Independent, Cincinnati Daily Gazette, and Washington Evening Star.

Finally, several articles were helpful to my research. These included Job Barnard's "Early Days of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia" in volume 22 of the Records of the Columbia Historical Society (1919), and Chief Justice John G. Roberts's article, "What Makes the D.C. Circuit Different? A Historical View," in volume 92 of the Virginia Law Review (2006).