To Protect and To Serve

The Records of the D.C. Metropolitan Police, 1861–1930

Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1 | Genealogy Notes

By John P. Deeben

The quiet atmosphere of the early spring night, already damp and overcast in anticipation of coming rain, 1 broke abruptly when the news burst into the unidentified police precinct around 11 p.m. In the midst of a growing commotion in the street that accompanied the report, the officer on duty quickly logged the information into the Detective Corps blotter. Dated April 14, 1865, the report simply read: "At this hour the melancholy intelligence of the assassination of Mr. Lincoln President of the U.S. at Fords Theatre was brought to this office and the information obtained . . . goes to show that the assassin is a man named J. Wilks Boothe [sic]." 2

Capturing the sorrowful reaction of the anonymous officer, this single blotter entry remains one of the most famous reports in the records of the Washington Metropolitan Police. Documenting events both spectacular and mundane, from the heinous national crime of a presidential murder to the routine arrests of pickpockets, streetwalkers, and drunkards, the records illustrate a compelling cross-section of the historical and social fabric of the District of Columbia from 1861 to the 1930s. They also document the background and activities of the many patrolmen, detectives, and other personnel who served on the force as well as the criminals who broke the laws.

Historical Background

Ever since Congress established the District of Columbia on July 16, 1790, the federal territory has sponsored a public police force in one form or another. From 1790 until 1804, local constables from Virginia patrolled their portion of the District, which included the city of Alexandria as well as Alexandria County. On the other side of the Potomac River, Maryland constables patrolled Washington County and the cities of Washington and Georgetown. After the incorporation of Washington in 1802, a city ordinance adopted September 20, 1803, provided for the first superintendent of police appointed by the mayor. A subsequent ordinance dated October 13, 1804, authorized the appointment of as many as four constables to enforce the local laws. This police force operated mainly during the day, until Congress on August 23, 1842, created an auxiliary watch to patrol the District at night. Initially, the federal government paid the salaries of the night watch, while members of the day force received compensation from the collection of fines and fees. On March 11, 1851, Congress established regular salaries for all constables. 3

The outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861 dramatically changed law enforcement in the national capital. Washington's population exploded, fueled by an influx of military personnel, war contractors, government workers, and office seekers. Also finding itself suddenly on the very border of enemy territory, with the newly established Confederacy raising fortifications just across the Potomac River, Washington instantly became a haven for many Southern sympathizers, profiteers, and other suspicious elements. The resulting disorder, confusion, and growing concern for the safety of the federal government prompted Congress to establish the Metropolitan Police Department—the first regular federal police force for the District of Columbia—on August 6, 1861. The congressional statute (12 Stat. 320) abolished the previous day and night forces and consolidated the District, including Washington, Georgetown, and the County of Washington, Maryland, into a centralized police district governed by a Metropolitan Police Board of five commissioners appointed by the President. The mayors of Washington and Georgetown also served as ex officio members. 4

The Police Board initially divided the District into 10 precincts. The First Precinct constituted the portion of Washington County east of the Anacostia River, while the Second Precinct included the county territory north of Washington City and between the Anacostia and Rock Creek. The Third Precinct comprised the remainder of Washington County west of Rock Creek, including Georgetown and the island of Analostan in the Potomac River. The Fourth through Tenth precincts corresponded respectively with the First through Seventh wards of Washington City. 5 The new police district did not include Alexandria County, which had been retroceded from the District of Columbia to Virginia by Congress on July 9, 1846.

One sergeant supervised the station house in each precinct. The remainder of the new police force consisted of up to 150 patrolmen as needed. All officers had to procure their own equipment, uniforms, and firearms. A superintendent of police, appointed by the board, headed the force. This organizational scheme remained intact, with minor changes to titles, number of precincts, and size of the force, until March 3, 1878, when Congress established a permanent local government for the District of Columbia. The new statute (20 Stat. 107) dissolved the Metropolitan Police Board and transferred supervision of the force to the new D.C. Board of Commissioners. 6

As the nation's first federal law enforcement agency, the Metropolitan Police participated in several high-profile investigations. The entire force turned out in response to the Lincoln assassination in 1865. Procuring horses from the Army quartermaster, police officers patrolled the streets alongside other cavalry and provost marshal units from the War Department. They enforced a strict shutdown of all entertainment venues, including saloons, concert halls, and beer gardens, and effectively sealed off the city from the surrounding countryside. 7 In 1881, police personnel also helped apprehend assassin Charles Guiteau after he fatally shot President James A. Garfield at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Depot on Sixth Street. Along the way, the Metropolitan Police protected the rights of citizens and property, guarded the public health, preserved the peace, and generally enforced law and order within the District. 8

Personnel and Administrative Records

The records of the Metropolitan Police, part of the Records of the Government of the District of Columbia (Record Group 351) at the National Archives, generally document both the people employed on the force and the law enforcement activities they performed. Several series of records provide useful information about individual officers. A single-volume register of appointments to the force (Entry 117) from 1861 to 1906 contains a litany of personal data, including the name of the policeman, date and place of birth, when and where naturalized (if applicable), age, former occupation, home address and size of family, date of appointment to the force, and date of resignation or dismissal. Sometimes additional notations regarding promotions, date of pension, and date of death also appear. The entry for patrolman Henry C. Volkman, for example, reveals that he was born in Maryland on May 20, 1841. At the time of his appointment to the force on January 31, 1867, he was 25 years old and said he resided as the head of a family of four at No. 31 Seventh Street in Georgetown. 9

Service records for members of the force (Entry 118) from 1861 to 1917 offer similar information as well as a chronological summary of service, including promotions, resignations, discharges, suspensions, and other personnel actions.

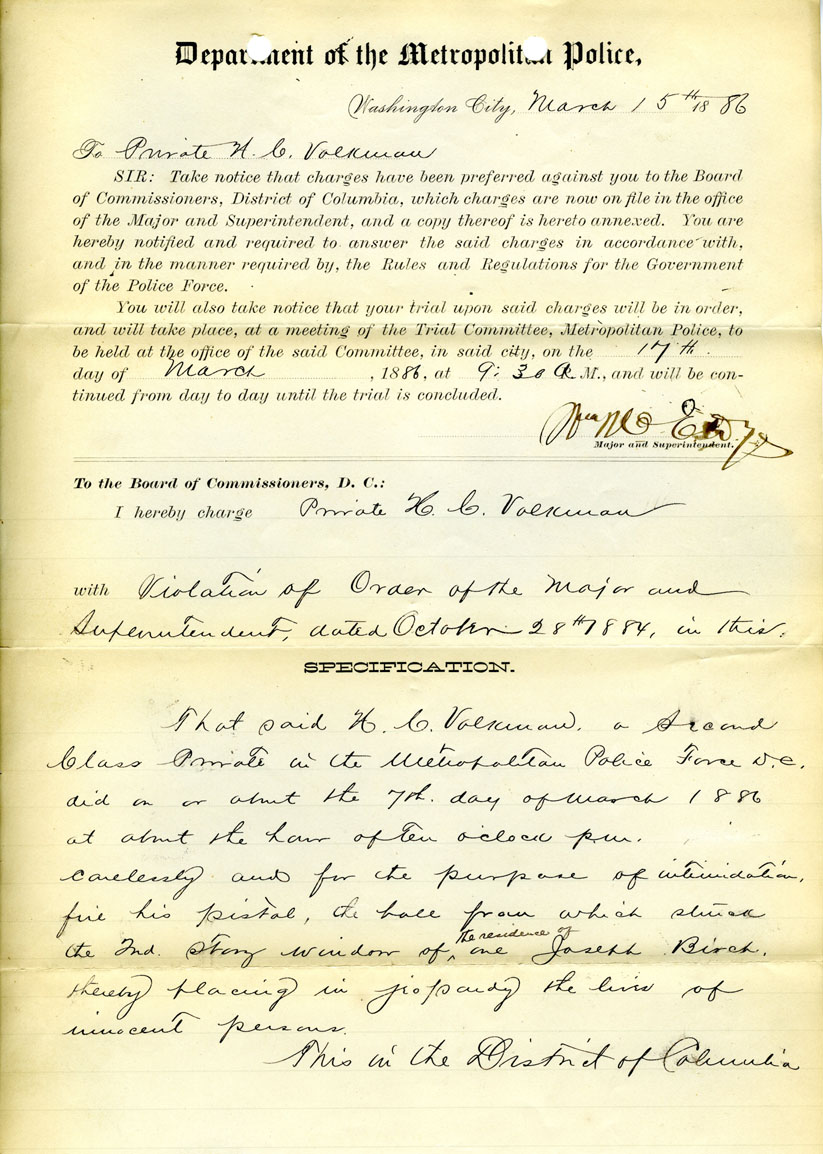

The entry for Volkman reveals considerably more detail about his conduct—and misconduct—during his employment. From October 12, 1870, to November 25, 1891, the Police Board tried Volkman 10 times for violations of rules and regulations, conduct unbecoming an officer, or general disobedience of orders. Most of the complaints were dismissed; however, Volkman did receive one reprimand on March 17, 1886, for carelessly discharging his sidearm while in pursuit of a burglar. The errant shot pierced the second-story window of a private residence, placing innocent lives in jeopardy. He also incurred a $25 fine and a warning for failing to patrol his beat for two hours during the early morning of November 21, 1888.

Despite these infractions, Volkman managed to obtain promotions to acting sergeant on February 18, 1889, and to sergeant on June 7, 1890 (although his rank was later reduced to first class private on September 1, 1897). Volkman received an honorable discharge from the force on May 31, 1903; pension payments of $50 a month commenced the following day. He died two years later on May 12, 1905. 10

Personnel case files (Entry 119) for policemen appointed from 1861 to 1900, with a few files dated as late as 1926, contain many of the original records that document an officer's career. The content of the files varies but frequently includes applications for appointment, letters of recommendation, records regarding physical and mental examinations, and chronological summaries of assignments. Paperwork relating to complaints and disciplinary actions frequently appear as well, especially copies of charges, subpoenas to witnesses, testimony submitted to the trial board, and related correspondence. 11

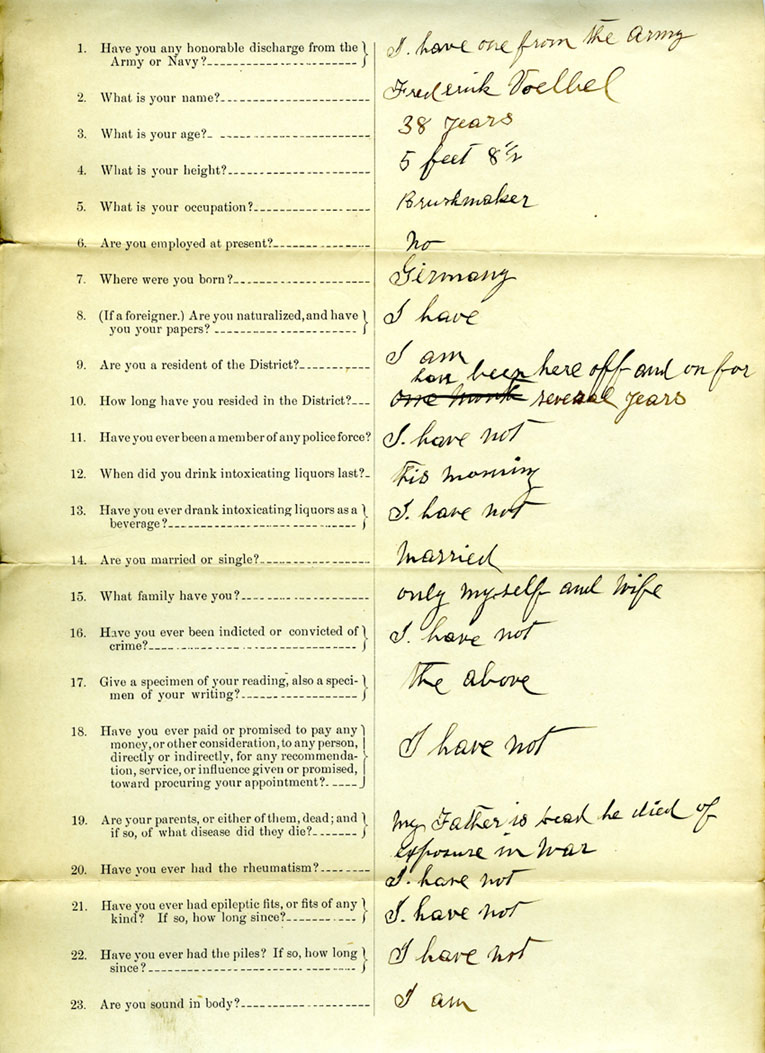

The personnel file of patrolman Frederick Voelbel reveals an interesting personal portrait. His application to the force, dated August 25, 1888, demonstrated that Voelbel, aged 38 years, was born in Germany and plied the brush-making trade. Married without children, he and his wife resided at 2131 H Street, N.W. Responding to a question about his parentage, Voelbel interestingly replied, "My Father is dead he died of exposure in war." An accompanying letter from the Adjutant General's Office of the War Department also verified that Voelbel served a five-year stint in the Fourth U.S. Cavalry from 1872 to 1878 under the alias "William H. Poole." A letter of recommendation from an acquaintance to A. A. Wilson, U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia, assured Voelbel's competency for the job: "I believe Mr. Voelbel will make a very good officer. If I did not think so I would not under any circumstances recommend him." 12

Similar to Officer Volkman, however, Frederick Voelbel also found himself in some disciplinary trouble, albeit with a more unfortunate ending. According to a specification of disciplinary charges attached to his file, Voelbel violated department rules on January 25, 1892, when he "did enter a grocery and liquor store, situate [on the] corner of 17th and Marian Streets, N.W., and remain therein ten minutes and did drink intoxicating liquors. This while on duty." The Trial Committee of the Metropolitan Police met on February 10, 1892, and eventually decided to terminate Voelbel, but he preempted their ruling by resigning from the force on February 26, 1892. Had police authorities paid closer attention to his application form, they might have noticed an earlier indication of Voelbel's drinking habits. In response to the question, "When did you drink intoxicating liquors last?," Voelbel bluntly answered, "This morning." 13

In addition to personnel issues, other series of records document the administrative activities of the police force. Several registers of oaths of office (Entry 120) from 1862 to 1878 record basic information about early police applicants, including name, job title, date of oath, and the name of the attesting officer. The oaths also identify the requisite qualifications for membership in the force, including U.S. citizenship, District of Columbia residency of at least two years, a physical stature of 5 feet 6 inches or greater, age between 24 and 45 years, no criminal record, and literacy in the English language.

Reflecting the national crisis that gave birth to the Metropolitan Police, the oaths also contain several anti–civil insurrection provisos, requiring appointees to foreswear support or service to any "pretended government, authority, power, or constitution, within the United States, hostile or inimical thereto," or to voluntarily give "aid, countenance, counsel, or encouragement to persons engaged in armed hostility" against the country. Only then do the oaths ask applicants to support and defend the Constitution of the United States. 14

Other administrative records include an early payroll book for 1861 to 1866 (Entry 121) showing monthly salaries for members of the force; two uniform account books for 1901 to 1906 (Entry 123) that record the type of clothing purchased, cost of the clothing, and payments made by individual officers; and a roll call book for the Third Precinct (Entry 122). Generally dated October 1888 to December 1895, the roll calls provide a daily record of attendance. Also included in the latter volume are several pages of roll calls for the Fourth Precinct from February 17 to December 16, 1873, and roll call data for special officers assigned to President Grover Cleveland's inauguration in March 1893.

Reflecting other major events in the national capital, an additional roll call exists for special officers called out in response to the arrival in Washington of Coxey's Army—a populist protest march of unemployed workers led by Ohio politician and socialist Jacob Coxey—on April 30, 1894. A series of general and special orders (Entry 116) for several precincts from 1862 to 1895 also document specific guidances for the police force, including changes in regulations or laws, verdicts in misconduct cases, personnel actions, and other general instructions and notifications. 15

Law Enforcement Records

Of particular value to the social history of the nation's capital, the Metropolitan Police records provide detailed information regarding criminals, illegal activity, and other aspects of law enforcement. Several volumes of daily returns of precincts (Entry 125) and arrest books (Entry 127) contain personal information about a variety of law-breakers. The daily returns, covering 1861 to 1878, generally consist of arrest reports entered by the sergeant of the precinct. The entries record the name of the person arrested, time of arrest, and the arrestee's age, race, nationality, occupation, marital status, and literacy. Additional information includes the nature and disposition of the offense, the arresting officer, and the name of the complainant.

Almost identical in nature, the arrest books cover 1869 to 1906 and offer a chronological listing of persons apprehended for various infractions in the Third Precinct and another unidentified precinct. For the most part, these records document petty crimes and misdemeanors, such as public intoxication, indecent language, and assault and battery. 16 A typical arrest entry from 1869 shows that John T. Reynolds, a 28-year-old cooper, was arrested on January 12 at 10:15 a.m. for running a wagon without a license. Patrolman Henry C. Volkman, still in the early stages of his career, made the arrest. Reynolds paid a $1.50 fine for the offense and was released from custody. 17

A similar arrest book (Entry 128), dated 1908 to 1918, documents the criminal activity of juvenile offenders. Again chronicling arrests in the Third Precinct, the volume lists the juvenile's name and address, age, race, the nature of the charges, the names of the complainant and arresting officer, and the disposition of the case. Offenses again ranged from petty larceny and assault to destruction of private property and fornication; penalties included fines, probation, and time in reform school.

Later arrest books and lists relating to traffic violations from 1913 to 1921 (Entries 130–131) document incidents involving horse-drawn vehicles as well as automobiles. These citations offer an interesting glimpse of the way the police applied law enforcement to the changing technology of transportation in the early 20th century. Some typical citations included those against Henry Fontaine on November 10, 1913, for "operating a fast automobile" at 18 miles an hour; John Burke on October 27, 1914, for driving the wrong way around a traffic circle; W. A. Harper on January 14, 1915, for failing to maintain front or rear lights on his automobile; and Thomas Mallory on June 19, 1917, for operating a "smoking" automobile. 18

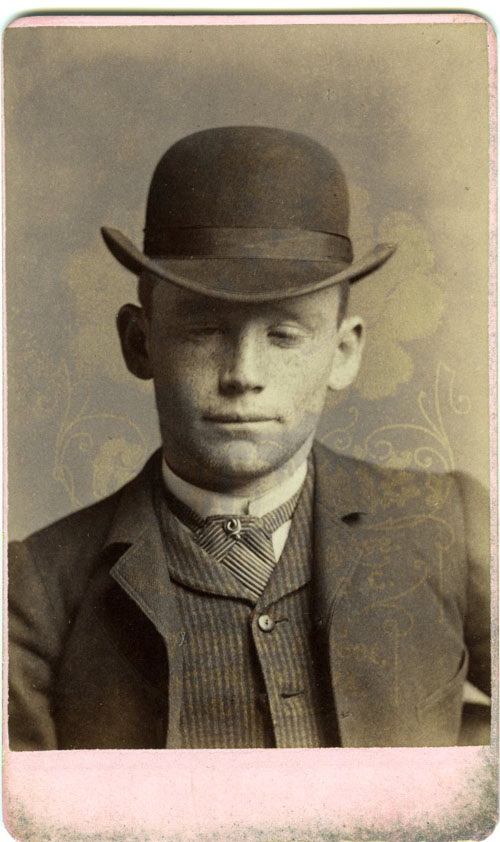

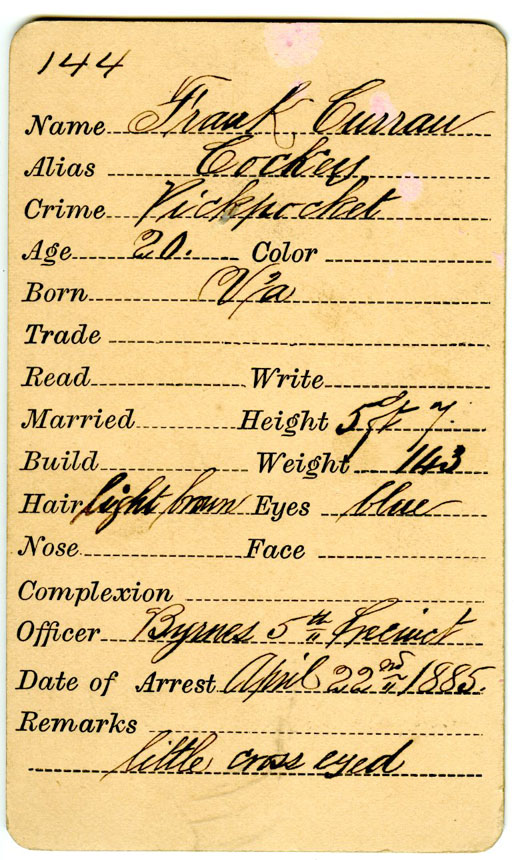

Identification books from 1883 to 1890 (Entry 138) provide perhaps the most interesting and visual documentation relating to criminals. Essentially comprising the equivalent of modern-day "mug shots," these records consist of cabinet-card photographs arranged in two volumes of multipocketed pages. The photographs reflect a wide racial and social stratum of individuals, from dapperly dressed swells and confidence men in top hats to rough-looking street thugs. The reverse side of each photograph offers detailed information about the alleged offender, such as name, alias, a complete physical description, occupation, literacy, marital status, nature of crime, date of arrest and arresting officer, and any pertinent remarks. Sometimes the remarks offer the most revealing insights. The photograph for Frank alias "Cockers" Curran, who was arrested as a pickpocket in the Fifth Precinct on April 22, 1885, contains the brief notation "little cross eyed"—a simple statement that may well explain why he got caught! 19

Several series of records document other law enforcement activities of the force. Police blotters (Entry 126) from 1862 to 1933 offer detailed chronological accounts of the daily activities of the force. Routine items described in the volumes include roll calls, assignments, and deliveries of equipment and supplies to various precincts. Crime-related information includes reports of disturbances, notification of complaints, arrests, investigations, and the recovery of lost or stolen property. Entries usually note the time of day and the names of officers involved in the reports. 20

Similar to the record of the Lincoln assassination in 1865, the Detective Corps blotter for July 3, 1881, recorded a detailed account of the apprehension of President James Garfield's assassin, Charles Guiteau, who was brought into the precinct station the previous morning about 9:30 by Officer Patrick Kearney and Special Policeman Scott, who were on duty at the Baltimore and Potomac Depot at the time of the shooting. The report entry described the assassin as 39 years old, 5 feet 7 inches in stature, about 125 pounds, with "shaggy thin whiskers and moustache, dressed in [a] dark suit of clothes, black slouch hat, dark brown hair, sallow complexion, nervous temperament." Possessions removed from the suspect at the station included a pistol marked "English Bull Dog," a pocket knife, 20 cents in silver coins, and some paper. Later that morning a witness came in and volunteered evidence placing the alleged assassin at the scene "whispering" to a possible conspirator, but after the first shot rang out the witness quickly left the depot. A subsequent blotter entry on September 19, 1881, noted President Garfield's passing at 10:35 p.m. at Long Branch, New Jersey. 21

Reports of public hazards (Entry 133) from 1879 to 1886 reflect some of the public safety responsibilities of the force. The reports identify problems discovered by officers while walking their beats, such as streets in need of repair, malfunctioning street lamps, and burst water mains. 22 On February 22, 1881, patrolling officers noted four dangerous holes in sidewalks and carriageways, three water hydrants out of order, and glass broken in a street lamp on 20th Street. A related series of accident reports (Entry 134) from 1901 to 1909 provides a chronological account of injuries to private citizens reported to Substation A in Anacostia. The reports usually describe the date and time of the incident, names of persons involved, a description of the event, and notations regarding police response. On December 21, 1903, a street car traveling south on Monroe Street struck the horse of a cart driven by Edward Scott of Sheridan Avenue. Scott sustained head injuries but was sent home in the police wagon. The investigating officer determined that Scott caused the accident by driving into the path of the car. 23

A large collection of property books (Entry 132), arranged chronologically from 1861 to 1908 and 1912 to 1914, provide information regarding police efforts to identify and recover lost or stolen possessions. The books also list property, usually various forms of weapons, confiscated by police while enforcing the laws. The reports relate mainly to the Fourth Precinct from 1862 to 1886 and the Third Precinct from 1888 to 1914. A related series includes license books (Entry 140) for various periods from 1877 to 1936. The volumes provide listings of licensed businesses within the Third Precinct, usually identifying the name of the establishment or type of occupation, address, and type of license. Businesses and professions requiring licenses typically included restaurants, barrooms, billiard halls, apothecaries, peddlers, hack and omnibus operators, junk dealers, and real estate agents. 24

Annual Police Reports

In addition to the textual records available in Record Group 351, published government documents and reports in the U.S. Congressional Serial Set offer an equally useful and probably underused resource for information about the Metropolitan Police. Congress routinely required federal agencies to produce a yearly report of their activities and accomplishments. The president of the Metropolitan Police Board authored the police report from 1861 until Congress abolished the board in 1878. Thereafter, the superintendent of police wrote the report for the department.

At various times, three different reporting authorities issued the annual police report to Congress. The secretary of the interior, who served as the intermediary between Capitol Hill and federal agencies within the District, initially received and published the police report with his own annual report from 1861 to 1872. From 1873 to 1877 the report appeared in the annual report of the U.S. attorney general. After the District of Columbia received a permanent local government in 1878, the report of the Metropolitan Police was included within the annual report of the D.C. Board of Commissioners. In the U.S. Congressional Serial Set, the annual police reports appear under Superintendent of Document (SuDoc) numbers I1.1 (Interior Department), J1.1 (Attorney General), and DC1.1 (Commissioners of the District of Columbia). 25

While the reports generally do not contain information about individual policemen, they do provide a detailed overview of the activities of the force as well as the nature of crime in the District. In addition to narrative descriptions about the condition and organization of the force, station houses in the District, and disciplinary matters, the reports contain lists of Police Board members and officers, including property clerks and the superintendent of police. They describe dispositions of the police force among the precincts, statistics about sick leave, and activities of the police telegraph office, detective corps, and members of the sanitary office, who responded to complaints about public health nuisances and transported the indigent poor and insane to hospitals and asylums. Statements also appear regarding public property and monies received and held by the police property clerk.

Concerning law enforcement issues, the reports provide statistical overviews of the disposition of cases, including the number of arrests in each precinct categorized by sex and age of perpetrator. They also publish statistics about offenses against people and property, arranged by type of crime, and reports describing the nativity and occupations of arrested persons. Lists of nuisance complaints frequently appear, as well as incidental work performed by patrolmen, including summaries of destitute persons furnished with temporary lodgings, lost children found, sick or disabled persons assisted, horses and cattle discovered astray and returned to their owners, open doors secured, and fires reported. Some reports occasionally expound upon crimes of local color, such as the punishment of boys "catching rides," which involved the practice of running after and jumping onto street cars and other moving vehicles.

The annual police reports in the U.S. Congressional Serial Set are usually available at large university or public libraries as well as many U.S. government depository libraries. At the National Archives, the textual records of the Metropolitan Police in Record Group 351 are in the custody of the Old Military and Civil Records Branch. Together, these resources tell the detailed and often compelling story of the lives and service of the nation's first federal law enforcement agency, as well as the misbehavior of shadier elements of society. From the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 to well into the early 20th century, the records offer a useful window into the social history of our national capital during a formative period.

John P. Deeben is a genealogy archives specialist in the Research Support Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. He earned B.A. and M.A. degrees in history from Gettysburg College and Penn State University.

Notes

1. Victor Searcher, The Farewell to Lincoln (New York: Abingdon Press, 1965), p. 32.

2. Entry listing the assassination of President Lincoln, Apr. 14, 1865; Detective Corps Blotter, March 29–October 9, 1865; Blotters, 9/1862–5/31/1933; Records Relating Primarily to Law Enforcement (Law Enforcement Records); Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of the City of Washington, the Territory of the District of Columbia, and the District of Columbia (Records of Washington and D.C.); Records of the Government of the District of Columbia, Record Group 351 (RG 351); National Archives Building, Washington, DC (NAB).

3. Dorothy S. Provine, Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Government of the District of Columbia, Preliminary Inventory (PI) 186 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Service, 1976), p. 30.

4. Ibid.

5. "Report of the Metropolitan Board of Police," Nov. 4, 1861, Ex. Doc. No. 1, 37th Cong., 2nd sess. (1861).

6. Provine, PI 186, pp. 30–31. Additional historical information is also available on the Metropolitan Police Department web site at http://www.mpdc.dc.gov.

7. Searcher, Farewell to Lincoln, p. 32.

8. Provine, PI 186, p. 30.

9. Entry for Henry C. Volkman, Jan. 31, 1867; Register of Appointments to the Force, 1861–1930; Records Relating Primarily to Personnel and Administration (Personnel and Administration); Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of Washington and D.C.; RG 351; NAB.

10. Henry C. Volkman Entry; Service Records of Members of the Force, 1861–1930; Personnel and Administration; Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of Washington and D.C.; RG 351; NAB. The service record only provides rudimentary information about disciplinary actions; details regarding Volkman's two convictions were also obtained from his personnel case file (Entry 119).

11. Provine, PI 186, p. 31.

12. W. W. Wetzel to A. A. Wilson, Jan. 19, 1889; Frederick Voelbel Folder; Personnel Case Files, ca. 1861–1950; Personnel and Administration; Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of Washington and D.C.; RG 351; NAB.

13. Specification of Disciplinary Charges, Feb. 8, 1892, and Application Form, August 25, 1888; in ibid.

14. Provine, PI 186, p. 31.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid., p. 32.

17. Arrest entry for John T. Reynolds, Jan. 12, 1869; Arrest Books, 1869–1906; Law Enforcement Records; Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of Washington and D.C.; RG 351; NAB.

18. Entries for Henry Fontaine, Nov. 10, 1913, John Burke, Oct. 27, 1914, W. A. Harper, Jan. 14, 1915, and Thomas Mallory, June 19, 1917; Record of Arrests for Traffic Violations, 1913–21; Law Enforcement Records; Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of Washington and D.C.; RG 351; NAB.

19. Photograph of Frank "Cockey" Curran, Apr. 22, 1885; Identification Books, ca. 1883–90; Law Enforcement Records; Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of Washington and D.C.; RG 351; NAB.

20. Provine, PI 186, p. 32.

21. Entry on the assassination of President James A. Garfield, July 3, 1881; Detective Corps Blotter, July 28, 1880–December 31, 1881; Blotters, 9/1862–5/31/1933; Law Enforcement Records; Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of Washington and D.C.; RG 351; NAB.

22. Provine, PI 186, p. 33.

23. Entry for Feb. 22, 1881; Reports of Public Hazards, 1879–86; and entry for Dec.21, 1903; Reports of Accidents, 1901–09; both in Law Enforcement Records; Records of the Metropolitan Police; Records of Washington and D.C.; RG 351; NAB.

24. Provine, PI 186, p. 33.

25. Superintendent of Documents, Checklist of United States Public Documents, 1789–1909, vol. 1: Lists of Congressional and Departmental Publications, 3rd ed. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1911; reprint Kraus Reprint Corp., New York, 1962), p. 397.