Sitting in Judgment

Myron C. Cramer’s Experiences in the Trials of German Saboteurs and Japanese War Leaders

Summer 2009, Vol. 41, No. 2

By Fred L. Borch

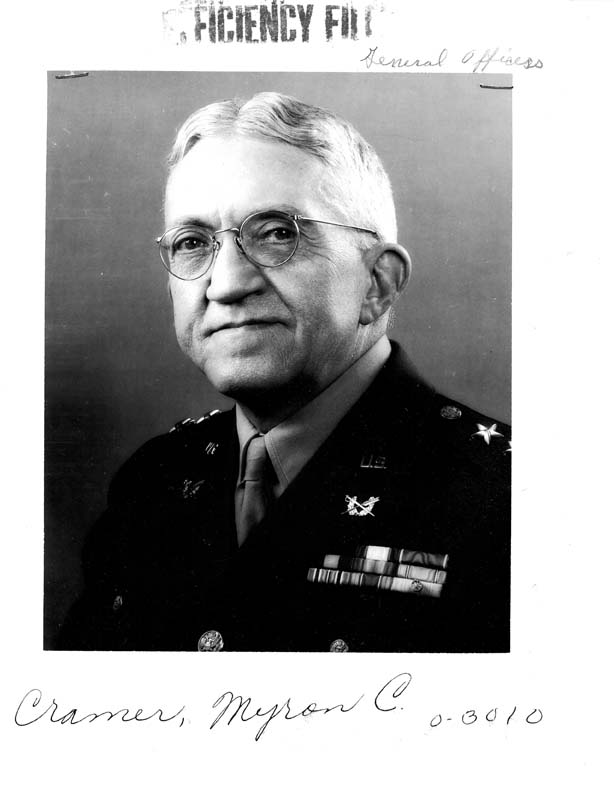

Thirty years after 29-year-old Myron C. Cramer enlisted in the Army as a cavalry private in the Washington National Guard, he reached the pinnacle of his career on December 1, 1941, as he exchanged his colonel's eagles for the two-star rank of major general as Judge Advocate General of the Army.

One week later, America was plunged into World War II. For the rest of that war, Cramer served as the top lawyer in the Army. In 1942 he made history when, in concert with U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle, he prosecuted German U-boat saboteurs at a military commission, becoming the first Judge Advocate General since the Civil War to prosecute at this type of tribunal.

At the end of the war, 63-year-old Cramer retired to private practice in Washington, DC; he no doubt believed that his years in uniform were over and he could expect his life to be more tranquil, if not uneventful. But this was not to be, for in 1946 Cramer made history again when he was called out of retirement and donned his uniform to serve as the sole American judge on the 11-nation war crimes tribunal in Tokyo, Japan. For the next two and a half years, Cramer decided the guilt of Japanese wartime political leaders, becoming the only Army lawyer in history to sit as a judge on an international military tribunal.

Cramer returned to the United States after the end of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, retired a second time, and ultimately did enjoy a civilian law practice until his death in 1966. While Cramer did speak in public about his experiences prosecuting the German U-boat saboteurs, he did not document his time as a judge in Tokyo. Fortunately, the records of both tribunals have been preserved in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), and this means that a thorough understanding of the facts and procedures in both trials is possible. But Cramer's unique role in these two historical events also can be examined because his complete military record has been preserved in NARA's Military Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. Consequently, although Cramer died more than 40 years ago, the detailed reports on his performance and other documents in his file permit a complete picture of his stellar military career to be assembled, including his role as prosecutor and judge.

Myron C. Cramer—Lawyer and Soldier

Born in Portland, Connecticut, on November 6, 1881, Myron Cady Cramer graduated from Wesleyan University in 1904 and Harvard Law School in 1907. After being admitted to the New York state bar in September, Cramer practiced law in New York City on the legal staff of Travelers' Insurance Company. In May 1910 he made a major change in his life when he moved from a bustling metropolis to the small town of Tacoma, Washington. Cramer had a general law practice for a few years before being appointed deputy prosecuting attorney for Pierce County.

Within months of his move, Cramer began his career as a soldier. According to his military records, he enlisted as a cavalry private in the Washington National Guard in January 1911. Later that year, he obtained a commission as a Guard second lieutenant in the First Washington Cavalry. Cramer's paperwork from this period shows that he was of medium height (5'7") and weight (125 pounds), with brown hair and gray eyes.

Promoted to first lieutenant in June 1915, Cramer was called into federal service a year later and served on the Mexican border with Brig. Gen. "Black Jack" Pershing until February 1917. At the end of this military duty, Cramer briefly returned to the prosecuting attorney's office before he and his fellow Guardsmen were again federalized for World War I. Then Captain Cramer went overseas in January 1918 and was sent to the Army General Staff College in Langres, France. Later, as chief of staff for the First Replacement Depot in St. Aignan, he was "in charge of the office and machinery through which an average of 40,000 replacements a month" were forwarded to all parts of the American Expeditionary Force. Cramer did extraordinarily well in overseeing the movement of the more than 500,000 men who ultimately were shipped through the depot. Comments in his efficiency report noted that he was a "man of excellent character" who "worked without regard to hours" and had "an indefatiguable [sic] attention to duty."

When Cramer returned home to the United States in late July 1919, he was a 37-year-old Officers' Reserve Corps infantry lieutenant colonel. He was married and had a son and a daughter. But, while he resumed his civilian law practice, Cramer had already decided that he liked soldiering—and life in the Army—better than lawyering in Tacoma. Even while he was on active duty in France, he had applied for a Regular Army appointment in the Judge Advocate General's Department.

Bureaucracies move slowly, however, and Cramer had to wait until July 1920 before his application was processed and he was invited to appear personally before a board of officers in San Francisco. The board was impressed with Cramer and, in recommending him for an appointment as a judge advocate major, made the following "general estimate" of him: "tact, appearance, intelligence, manner, personality well above average; a high class man; impressed the board very favorably; well educated and will be of great value to the service; quiet, unassuming and a polished gentlemen; law brief submitted by candidate show him well qualified professionally."

The Judge Advocate General's Department concurred and offered Cramer a commission as a Regular Army major. After accepting this appointment, Cramer served in a variety of assignments and locations over the next 20 years. He did a two-year assignment with the Third and Fourth Divisions, taught as a law professor at West Point, and graduated from the two-year Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Although Cramer had volunteered for duty in China, he was instead sent to Manila in 1934, where he served as the top Army lawyer in the Philippine Department for three years. Cramer's records show that his strength as an attorney was contract law, particularly in the area of negotiating Army procurement contracts. This explains why he had a total of eight years (from 1930 to 1934 and 1937 to 1941) in Washington, DC, as chief of the Contract Division. Having amassed an outstanding record as an Army lawyer, Colonel Cramer was selected to be the Army's top lawyer in 1941.

Trial of the German U-boat Saboteurs

Little more than six months into his job, Cramer found himself working alongside U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle in an extraordinarily high-profile criminal matter: the trial by military commission of German U-boat saboteurs.

In June 1942, eight German-born agents, all of whom had previously resided in the United States and spoke English, traveled across the Atlantic by U-boat. Four landed on Long Island, N.Y., and four came ashore in Florida. All had been trained as saboteurs and had brought with them dynamite, fuses, and $180,000 cash (about $2.3 million in today's money). The Germans had secret instructions showing the locations of U.S. aluminum and magnesium production facilities, electric power plants, bridges, tunnels, and other infrastructure important to America's war effort, and they intended to wreak havoc through sabotage.

After the Germans arrived in the United States, however, one of their leaders, George Dasch, turned himself in to the Federal Bureau of Investigation and, as a result, the FBI was able to quickly apprehend the other men.

At first the government intended to try the men in U.S. District Court. The Roosevelt administration soon decided, however, that this forum was ill-advised because a civilian trial would be open to the public, and this would undermine the desired impression that brilliant detective work by federal law enforcement agents had exposed the saboteurs' plans. After all, newspapers and radios were loudly trumpeting the FBI's remarkable success, and there was good reason to believe this would cease were the truth to be revealed: that the plot had been discovered only because one of the saboteurs had turned himself into the authorities and then exposed his compatriots.

Because the government did not want Hitler to know how easy it had been for Germans to land on U.S. shores—and to deter any such future sabotage operations—Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Attorney General Biddle decided that a military commission—which could be closed to the public—was the best course of action. The fact that the German Reich had secretly landed its agents in civilian guise on U.S. soil was an act of war, and the planned sabotage constituted a violation of the laws of war. While there was some disagreement among lawyers in the Roosevelt administration, the majority view was that these facts meant that a trial by military commission was both lawful and proper.

But there was another reason, and perhaps the most important reason, to try the German saboteurs by military commission—and it was Myron Cramer who first raised it. On June 28, 1942, Cramer wrote to Secretary Stimson that a civilian court was the wrong forum for the German saboteurs because "the maximum permissible punishment . . . would be less than is desirable to impose." As Cramer explained, this was because the Federal rules of evidence would make it difficult to obtain a conviction for sabotage (a 30-year offense) in U.S. District Court, making it likely that the men might only be convicted of conspiracy (a three-year offense). A trial by military commission, however, was not bound by federal procedural or evidentiary rules, and there was no limitation on any sentence that could be imposed, including the death penalty.

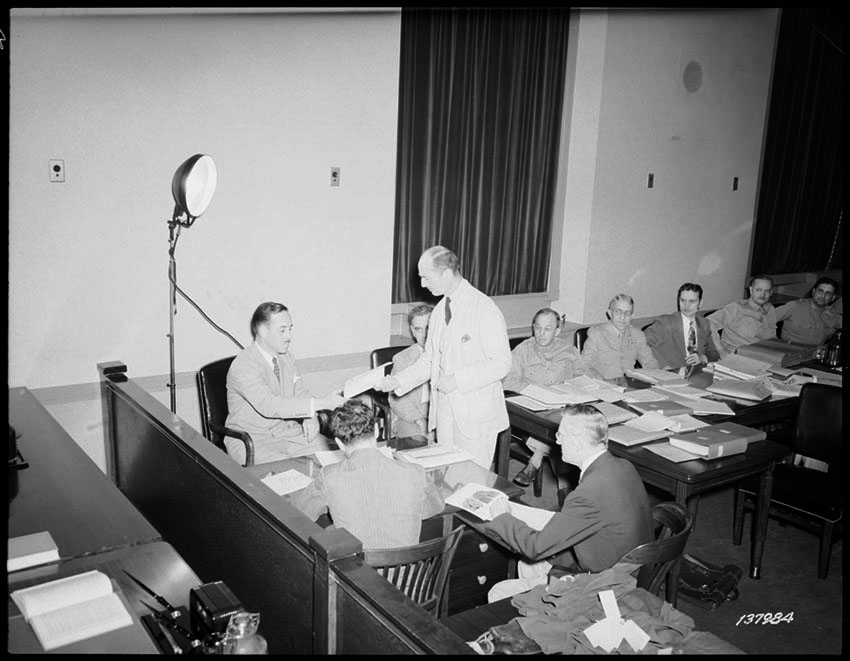

When Stimson met with Biddle the next day, the two officials agreed that trial in a civilian court was ill-advised and that a military commission would best meet the needs of the government. Based on their recommendations, President Roosevelt established the military commission by proclamation on July 2, 1942, and also issued an executive order appointing Biddle and Cramer as co-prosecutors. That same order selected four major generals and three brigadier generals to serve as the seven-member panel to decide guilt and determine an appropriate sentence. Finally, the order appointed military defense counsel to represent the accused Germans.

Matters moved quickly for Cramer since he and Biddle began presenting evidence to the tribunal on July 8. Preliminary arguments and the taking of testimony took 16 days—an average of two days for each accused. The military commission completed its work on August 1, when it found all eight defendants guilty of "attempting to commit sabotage, espionage, and other hostile acts" and "conspiracy" to commit these same offenses. Cramer and Biddle argued that the Germans must be sentenced to death, and the commission agreed. Roosevelt approved the death sentence for six of the eight men, and those six were electrocuted on August 8, 1942. The other two were imprisoned and later deported to Germany after the war. The U.S. Supreme Court later upheld the jurisdiction of the military commission, and the lawfulness of its proceedings, in the case of Ex parte Quirin, which continues to be cited with approval by today's Supreme Court.

Cramer's work as co-prosecutor was praised by his superior as "historic evidence of his legal ability and sound judgment." He and Biddle had successfully completed the first military commission convened by a President and had achieved the best possible results for the government.

Cramer continued to serve as the top Army lawyer for the rest of World War II. It was a challenging job to have in an Army that had transitioned from peace to war and grown to 8 million men and women. When Cramer retired on December 1, 1945, after four years as the Judge Advocate General, he was lauded at the highest levels for his "consummate legal skills" and his organizational abilities in running a legal operation that had grown from 190 uniformed lawyers in 1941 to more than 2,160 judge advocates in 1945 and had offices located throughout the world.

Tokyo War Crimes Trial

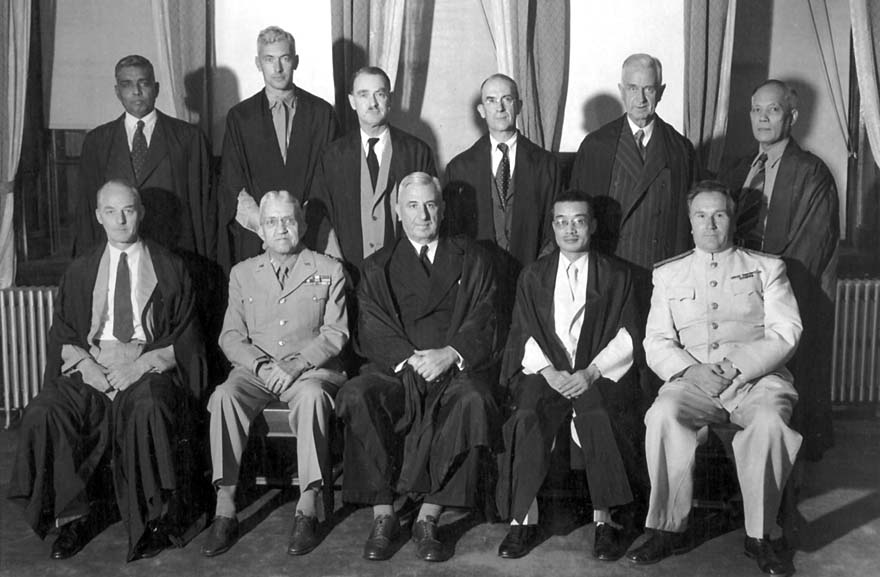

After retiring on December 1, 1945, Cramer and his wife settled in Washington, DC, and he began to build a civilian law practice. No doubt he believed that tranquility would be the norm in his life. But in June 1946, Cramer learned that John P. Higgins, chief justice of the Massachusetts supreme court, who had been appointed as the American judge for the upcoming Tokyo War Crimes Trial, had abruptly resigned. This was embarrassing, as the trial was under way (having started in May), and Higgins had been hearing evidence in Tokyo for two months. In this emergency situation, and with little time to fill this vacancy, the War Department asked Cramer if he would consent to being recalled to active duty to take this important judgeship. Cramer agreed, and his appointment as the lone American judge on the "International Military Tribunal, Far East" was personally approved by U.S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark and Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers General of the Army Douglas MacArthur.

Cramer's military records show that he was recalled to active duty on July 10, 1946, left Washington, DC, by air five days later, and arrived in Tokyo on July 20. He took his seat on the tribunal two days later, on July 22, 1946. In a January 1947 memorandum, Cramer wrote that the War Department initially believed "the trial would only last six months" and that the proceedings "would be over by Christmas" 1946. Since Christmas had passed, however, and it was January, Cramer now predicted that "it will likely be the 4th of July [1947] before the case is finished." Even that estimate proved wrong, as the Tokyo War Crimes Trial would consume a total of two and a half years before reaching a verdict in November 1948.

The International Military Tribunal of the Far East, or Tokyo War Crimes Trial, as it is more commonly known, was the Pacific counterpart to the war crimes trials held in Nuremberg from November 1945 to October 1946. Cramer and his 10 fellow judges (from Australia, Canada, China, France, Great Britain, India, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Philippines, and the Soviet Union) sat in judgment on 28 Japanese military and civilian leaders. Most of the defendants were military, the best known being Tojo Hideki, an Army general and Japan's political and military leader (he served as prime minister from 1941 to 1944). But civilian leaders also were on trial, such as Hirota Koki, a career diplomat, who was charged with failing to prevent Japanese atrocities in Nanking, China, during a six-week period starting in mid-December 1937. Notably missing from the list of defendants, however, was the Japanese emperor, Hirohito, whom many observers expected would be tried for war crimes as well.

Just as at Nuremberg, the chief purpose of the Tokyo trial was to hold high-level political and military leaders accountable for the waging of a brutal, aggressive war that had taken the lives of millions of innocent men, women, and children. Consequently, the defendants—all of whom had been wartime leaders in Japan—were charged with "crimes against peace," which was defined as conspiring to wage, and waging, an "aggressive war" in contravention of "international law, treaties, agreements or assurances." But the Japanese also were accused of having committed "crimes against humanity" and "war crimes," and as a result, the judges heard horrific evidence of murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhuman acts committed by Japanese troops.

It soon was obvious that the voluminous evidence—which ultimately consisted of thousands of pages of documents and testimony from 419 witnesses—had to be organized for the Tokyo tribunal's use. In the division of labor that followed, Cramer took on the task of preparing a dossier on Japanese "war crimes committed by the Japanese Armed Forces in territories occupied by them."

Cramer and his assistant, Army lawyer Lt. Col. Howard H. Hasting, gathered and organized evidence of war crimes presented to the tribunal by the prosecution. Their work, contained in a two-volume "Brief of Evidence of Conventional War Crimes and Atrocities" records how Japanese soldiers murdered Chinese civilians as early as August 1932, when villagers in Pingtingshan were ordered "to assemble along a ditch and kneel; machine guns were then mounted behind the victims and used to mow them down; those not killed by the machine guns were bayoneted." Considerable evidence was collected relating to the Rape of Nanking in 1937, with Cramer showing that some 30,000 Chinese soldiers "who had laid down their arms and surrendered . . . were machine gunned and bayoneted to death and their corpses burned with kerosene" and that Japanese soldiers had "raged like savages" in brutally raping thousands of Chinese women. Cramer ultimately concluded that between 260,000 and 300,000 Chinese civilians had been massacred by the Japanese army in Nanking and that this "wholesale murder of civilian men was conducted apparently with the sanction of [Japanese] Army authorities."

Evidence of Japanese war crimes against Allied prisoners of war was particularly disturbing to Cramer, given that he had spent his life in uniform. He compiled evidence of Americans and Filipinos "tortured, shot and bayoneted" while on the Bataan Death March and proof of the "starvation, torture and neglect" of Americans taken prisoner at Corregidor. Lesser-known war crimes also were included in the compilation. For example, pages from the diary of a Japanese soldier captured in New Guinea recorded the March 1943 murder of an American flight officer. He "was made to kneel on the bank of a bomb crater filled with water" and then beheaded by a Japanese officer wielding his "favorite sword." Cramer's work showed that war crimes committed against prisoners of war were routine; one exhibit referenced in Cramer's compilation recorded that "a party of 123 Australian soldiers . . . were divided into small groups of ten or twelve . . . marched into the jungle and murdered by decapitation and shooting."

Cramer's "Brief of Evidence" contains hundreds of similar war crimes perpetrated by Japanese personnel and was made part of the official Tokyo War Crimes Trial record when the 11-member tribunal rendered its verdict. That came in November 1948, when 25 of the defendants were found guilty of at least one crime, including conspiracy, waging an aggressive war, and ordering, authorizing, and permitting atrocities. Seven of the Japanese defendants were sentenced to be hanged, and the remainder received sentences to imprisonment ranging from seven years to life.

Eight of eleven judges concurred fully in the majority opinion, including Cramer. He had, in fact, played a key role in authoring this important opinion, because he was the chairman of the drafting committee. But it had been hard going: Cramer and his committee had spent seven months hammering out a final opinion acceptable to the majority. Two of the three dissenting judges did not quarrel with the overall result (the French judge, for example, dissented because Emperor Hirohito had not been indicted). Only one judge, from India, dissented completely from verdict, chiefly because he believed that aggressive war and the other crimes charged were not a part of international law.

Cramer's participation at Tokyo made him an integral part of legal history, for this war crimes trial provided part of the foundation for the international humanitarian law that exists today. The decision in Hirota's case is illustrative. A civilian, professional bureaucrat, and a member of the cabinet, Hirota's inaction when informed about Japanese war crimes perpetrated against Chinese civilians in the rape of Nanking caused Cramer and his fellow judges to find him "derelict in the performance of his duties in not insisting . . . that immediate action be taken to put an end to the atrocities." As Cramer and his fellow judges saw it, Hirota's "inaction amounted to criminal negligence" under international law and consequently he not only was guilty as charged but merited the ultimate penalty: death by hanging.

This was an important legal result because it established that a civilian may be accountable for war crimes even though he was not in the military chain of command. The importance of Hirota has been lasting: the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) cited the Hirota decision in issuing its September 1998 judgment against a former Rwandan mayor, Jean-Paul Akayesu, finding him guilty of genocide, incitement to commit genocide, and crimes against humanity.

Life after the Army

When Cramer retired a second time on March 31, 1949, he was 67 years old and had been soldiering for more than 38 years. He almost certainly looked forward to a more tranquil future at his home on Fordham Road NW in Washington, DC. Cramer had once told his wife that he believed he had been "allotted . . . three score and ten years," so he may have thought he had but a few years to live. But he was wrong and continued to live a vigorous life until passing away on March 25, 1966, at age 84.

Fred L. Borch is the regimental historian and archivist for the Army's Judge Advocate General's Corps. A lawyer (J.D., Univ. of North Carolina) and historian (M.A., Univ. of Virginia), he served 25 years active duty as an Army judge advocate before retiring from active duty in 2005. This is his third article for Prologue.

Note on Sources

Myron Cramer's Official Military Personnel File is preserved in the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. Details on Cramer's career as a soldier and his role in the U-boat saboteur military commission comes from this file and a speech he gave to the Washington State Bar Association in September 1942 (reprinted in Washington Law Review & State Bar Journal 17: 247–255 [1942]).

Cramer's memorandum advising that a military commission was the best forum at which to prosecute the German captives is located in the German Saboteurs file, Records of the Office of the Secretary of War, Record Group (RG) 107, National Archives at College Park, Maryland (NACP). The record of trial is located in Court Martial Case File 334178, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General, RG 153, NACP. The Supreme Court decision in the case Ex parte Quirin was published in United States Supreme Court Reports 317: 1 (1942).

Photographs relating to the investigation, capture, and trial of the U-boat saboteurs are located in Administrative History, Records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, RG 65, NACP. The historical archives maintained at the Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School, Charlottesville, Virginia, has a copy of the "Brief" prepared by Cramer and Hasting.

Much of the background material on the German U-boat saboteurs is to be found in Louis Fisher, Nazi Saboteurs on Trial: A Military Tribunal and American Law (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003). This is the best secondary source on the trial.

Primary materials on the Tokyo War Crimes Trial are in various locations. Records of the War Crimes Branch, in Records of the Judge Advocate General (Army), RG 153, NACP, contain general administrative information relating to Pacific war crimes. Special War Problems Division Subject Files, in General Records of the Department of State, RG 59, NACP, contain many reports on the mistreatment of American prisoners of war in Japanese camps. Records of the Legal Section, in General Records of General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers Operational, RG 331, NACP, contain specific information about the abuses suffered by U.S. military personnel, including a large number of questionnaires completed by former prisoners detailing their mistreatment. The best published primary source on the trial is R. John Pritchard and Sonia M. Zaide, eds., The Tokyo War Crimes Trial, 22 vols. (New York: Garland Press, 1981–1987).

Details on Cramer's role in the Tokyo tribunal comes from his St. Louis military personnel file.

The best general source on Japanese war crimes in World War II is Philip R. Piccigallo, The Japanese on Trial (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979). For more details on Hirota and Nanking, see Iris Chang, The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II (New York: Basic Books, 1997). Researchers interested in Japanese war crimes also should consult Edward Drea et al, Researching Japanese War Crimes Records: Introductory Essays (Washington, DC: NARA, 2006). This last resource was produced by the Interagency Working Group, Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records.