Institutional Memory

The Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital at the National Archives

Summer 2010, Vol. 42, No. 2

By Frances M. McMillen and James S. Kane

© 2010 by Frances M. McMillen and James S. Kane

In 1921, Bryan Hall's doctor at St. Elizabeths Hospital wrote in his file, "This old man has been in this institution 47 years and states that he is now anxious to leave."

Hall, at 66 years old, had spent nearly every year of his adult life in the nation's first federally operated hospital for the treatment of people with mental illnesses. Bryan Hall's file is part of Record Group 418, the massive collection of material documenting the history of St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C. Hall's case, along with the photographs, architectural drawings, administrative records, and thousands of patient files, all tell part of the hospital's story.

Well-known and unknown citizens, prominent architects and Civil War veterans are represented in the collection and provide a wealth of information to researchers in a variety of fields, including genealogy, architecture, and Washington history.

Hall was admitted on May 4, 1874, five days before his 19th birthday. When he arrived, the institution was known as the Government Hospital for the Insane and consisted of three patient buildings overcrowded with nearly 700 people. When he died at the hospital in 1923, never having left, there were several thousand patients living on a sprawling campus of nearly a hundred buildings bisected by a public road. During the 49 years Hall was hospitalized, four superintendents led the institution and more than 20,000 people were treated. Hall was patient number 3,627.

St. Elizabeths was founded in 1852 to provide "the most humane care and enlightened curative treatment" for members of the Army and Navy and residents of the District of Columbia. The hospital is still in operation today. It treats a few hundred in-patients and is managed by the District of Columbia. The hospital is probably best known as the home of John Hinckley, Jr., who attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in 1981. He has been at St. Elizabeths for nearly 30 years.

When the District of Columbia took control of the hospital in 1987, many of the institution’s historic buildings remained the property of the federal government and went unoccupied for several years. Plans are in the works to locate the headquarters of the Department of Homeland Security on the west campus, the most historic section of St. Elizabeths. The oldest building, where Hall and thousands of others lived for well over a hundred years, will house the secretary's office.

Bryan Hall was the son of Reverend Charles H. Hall, the rector of Epiphany Episcopal Church, located near the White House. From 1856 until 1869, Reverend Hall led a parish whose members included Abraham Lincoln and, prior to the Civil War, Jefferson Davis. Reverend Hall read from the Episcopal burial service at President Lincoln's White House funeral. In 1869 he moved his family to New York when he became the Rector of Holy Trinity Church in Brooklyn. After Bryan finished school, he enrolled in the Navy for a short period of service. It is unclear from his file what occurred to require hospitalization, but following treatment in New York, Hall was sent to St. Elizabeths. Though the hospital was founded to care for members of the military and the poor residents of Washington, St. Elizabeths accepted paying patients when room allowed. Bryan Hall had served in the military, but his family paid for his care.

St. Elizabeths was a relatively young institution when Hall arrived. The hospital admitted its first patient in 1855. Prior to its establishment, the capital's mentally ill were sent to the city jail; almshouses in Washington, Alexandria and Georgetown; or hospitals primarily in Maryland. Historian Frank Millikan, in his study of St. Elizabeths, wrote that doctors, public health officials, and city leaders saw the needs of this segment of the population and sought to establish an asylum in Washington in the mid-1830s. In 1838, Richard Lawrence, the would-be assassin of President Andrew Jackson, was incarcerated in a Washington jail. Lawrence had been determined to be a "lunatic." In April of that year, the Committee on the District of Columbia conducted a study to determine how quickly an asylum could be constructed for those, like Lawrence, who were in prison and needed mental health care. Lawrence would later be among the first patients admitted to St. Elizabeths in 1855.

The committee proposed the construction of a hospital for the 30 or 40 mentally ill District residents as well as an estimated 120 people who did not reside in the city but were ill, indigent, or helpless. Many of the latter group were veterans who descended upon the capital seeking "real and imaginary claims upon the justice or bounty of their country" and remained in the city without any means of paying for medical treatment. It was estimated that a hospital built for these purposes would cost $75,000, but the proposal ultimately went nowhere.

In the 1840s the issue resurfaced, and the city considered converting the local jail into an asylum, but the building was ultimately seen as unsuitable for this purpose and it was instead turned into a small infirmary. Washington, until the founding of the Government Hospital, would pay Maryland to care for its mentally ill residents.

Momentum to establish a hospital grew again in the 1850s, and Dr. Thomas Miller was one of the key figures involved. Miller was president of the board of health and founder of the infirmary located in the former jail. He was concerned with the current and future needs of the city's mentally ill residents. In 1852, their number in the District of Columbia was low compared to the states, but as Miller pointed out to the commissioner of public buildings, who had written to the doctor in January to express his own concerns about the mentally ill in the city, it was likely to grow.

While Miller and others were in Washington trying to establish a hospital, Dorothea Dix was delivering a memorial in Maryland on the overcrowded conditions of its state hospital in Baltimore. Dix had been advocating on behalf of the mentally ill since the early 1840s after witnessing the horrific conditions in which the sick were housed—often ill-cared for in jails and almshouses. She wrote impassioned memorials to state governments for the removal of the mentally ill from these institutions and argued that asylums should be established for their care. Her efforts led to the founding of public hospitals in several states including New Jersey, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. Dix came to Washington in 1848 to work toward the dedication of more than 12 million acres of public land throughout the country on which to establish a network of public asylums. She spent several years in the city working for this effort. Though it ultimately failed when President Franklin Pierce vetoed a bill to dedicate the land, Dix played a large part in the establishment of the Government Hospital.

In her Maryland memorial Dix noted the additional burden District residents placed on the Baltimore institution because of the capital’s lack of a hospital. Miller continued his efforts to establish a hospital in the District by writing to members of Congress following his communications with the commissioner of public buildings. In August, two members of Congress, one member citing Miller's correspondence and letters to local papers from city residents concerning Washington's mentally ill, introduced bills for the establishment of the hospital. One bill called for an appropriation of $100,000 for the construction of a hospital in the capital for the care of both Washington and the military's mentally ill. It passed on August 31, 1852, and the Government Hospital for the Insane was established.

Dr. Miller hoped to have a major role in the operations of the institution but was instead appointed to the hospital's Board of Visitors, where he served until 1860. Dix helped select the site for the institution, and when in Washington, she often stayed in a room set aside for her in the superintendent’s quarters. She remained involved with the hospital until her death in 1887.

At the time of the hospital's founding, an era of reform was under way in the treatment of those suffering from mental illnesses. The introduction of moral treatment, or moral therapy, was a great part of the movement. For many newly founded asylums, including the Government Hospital for the Insane, it was a major component in patient care.

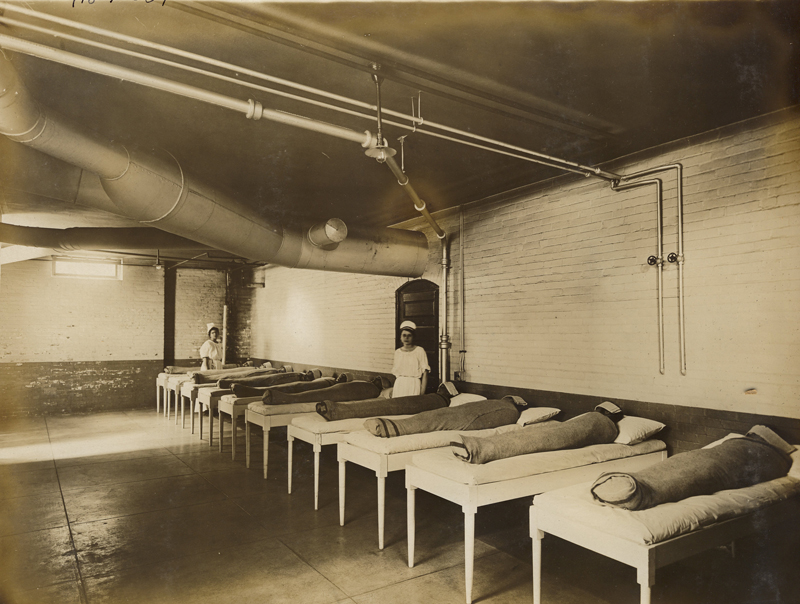

Moral treatment had its origins in England and France and involved providing patients with comfortable surroundings in which to live, good food to eat, and caring for them with kindness and respect. Patients were removed from restraints and given freedom to enjoy the outdoors. They worked on hospital farms and gardens and were encouraged to exercise. Patients were provided with entertainment in the form of lantern slide shows and musical performances. It was believed that if the ill were treated with dignity and removed from the harsh conditions in which many of them lived, they would have a better chance of recovery. The asylum environment, including the buildings patients lived in, and the views, walks, and gardens that were often a part of the institution's landscape, were all part of the therapy.

The Government Hospital was designed with moral treatment in mind. When the main structure, known as the Center Building, was finished in 1860, it housed patients primarily in single rooms with sitting and dining rooms on most wards. The hospital was not the first institution to care for African Americans suffering from mental illnesses, but it was the first to build facilities for their care. The West Lodge for African American men and the East Lodge for African American women were modest structures designed to house fewer than 50 patients each. Until construction of the lodges was completed—the West Lodge in 1856 and the East Lodge in 1861—black and white patients lived in the Center Building. The campus had a small zoo, pleasure walks, a farm on which to work, and striking views of downtown Washington, Alexandria, and the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers.

The founders of the Government Hospital aspired to create an institution that would be a leader in patient care and an example the states could follow in the operation of their public hospitals. Dr. Charles H. Nichols, a 32-year-old assistant physician at the Bloomingdale Asylum in New York, was selected as the first superintendent at the suggestion of Dix. Nichols was informed in his letter of appointment from the secretary of the interior, whose agency was in charge of the hospital: "It is the desire of the President that the proposed hospital shall be a model institution, embracing all the improvements which science, skill and experience have introduced into modern establishments." Nichols shared this desire, as well as the hope the institution would be a Washington landmark. In 1852 he reported on the progress of construction and stated, "The institution itself will be one of the most conspicuous ornaments of the District, and will be visible to more people, and from more points, than any other structure, excepting, perhaps, the Capitol, and the Washington Monument when completed."

Doctor Nichols and Dorothea Dix selected the site for the hospital partially because of its impressive view from and towards the nation's capital. In his 1853 State of the Union address, President Pierce expressed his high hopes for the hospital. Once completed the institution, Pierce said, "will prove an asylum indeed to this most helpless and afflicted class of sufferers, and stand as a noble monument of wisdom and mercy."

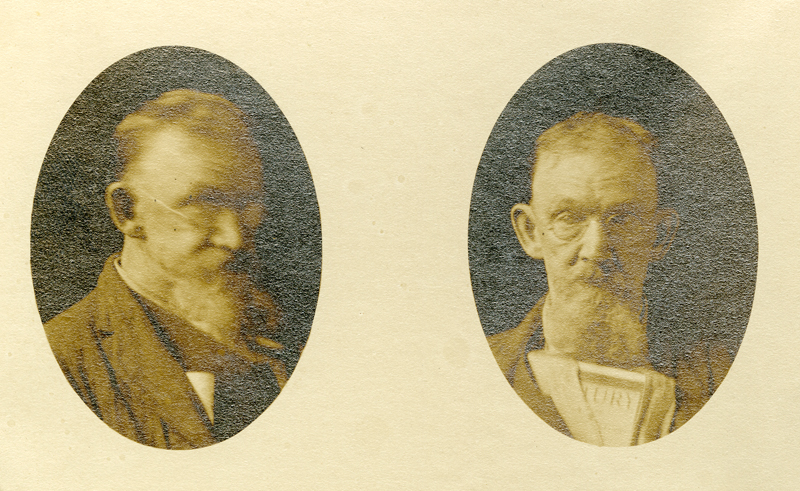

For many years the hospital achieved its goal of being the leader in mental health care. The first five of the institution's superintendents were elected president of the American Psychiatric Association. Four superintendents dedicated more than two decades of their lives to the hospital. Dr. William Alanson White led the hospital beginning in 1903. White moved the institution out the era of moral treatment with the introduction of psychotherapy and psychology and promoted research and scholarship among his medical staff. New programs and departments including internal medicine, occupational therapy, and social work began. He established patient newspapers, set up beauty parlors, and relieved overcrowding with the construction of several buildings.

During White's tenure the Government Hospital for the Insane became officially known as St. Elizabeths—the name for the land patent upon which the institution was built. Beginning as early as the Civil War, patients had been referring to the hospital by that name. Doctors Nichols and Godding had both expressed displeasure at the wordy formal name and the inclusion of the word insane. In his annual reports to Congress, White repeatedly requested a change. In the 1905 he wrote that patients' families were including self-addressed envelopes for return correspondence so that their association with the hospital could be kept private. "The official stationery of the hospital goes all over the United States and into thousands of homes, and contains printed thereon reference to the one disease in the whole category of human ailments about which people are most sensitive. It is unnecessary that this should be so, and it could easily be remedied." In 1916, St. Elizabeths Hospital became the institution's official name.

Following White's death in 1937, Dr. Winfred Overholser became superintendent and remained at St. Elizabeths until his retirement in 1962. During his tenure another long list of invasive and noninvasive treatments was implemented, including psychodrama, art, dance, and group therapy and electroshock and insulin shock therapy. During Overholser's tenure, tranquilizing drugs were introduced. These medicines, along with a 1946 act transferring the care of members of the military to Veterans Administration facilities and the deinstitutionalization and community health care movements, ultimately led to a drastic reduction of the number of people hospitalized at St. Elizabeths. More than 7,000 people received inpatient care during the 1940s. In the 1980s, around 1,200 patients were hospitalized. Currently there are only a few hundred.

Along with the accomplishments and milestones in the development and history of the hospital and the treatment of mental illness, there also were failings. As any student of the history of mental health care knows, or any person or family member of someone undergoing treatment understands, invasive therapies intended to ameliorate symptoms and treat disease sometimes wound up doing more harm than good. Though the founders of hospitals like St. Elizabeths had noble intentions and designed their institutions with a patient’s benefit in mind, hospital life often did not live up to their ideals. By the time Bryan Hall died in 1923, St. Elizabeths had been investigated three times for mismanagement and charges of patient abuse. Three years after his death, it was investigated again.

Originally planned with a belief in a high rate of curability, St. Elizabeths for many, as illustrated by Hall, became a long-term care facility. Many admitted in 1855 remained hospitalized until their deaths in the early years of the 20th century. On February 21, 1855, Mary E. Walker became the first female patient at the hospital. Walker was 23 and suffering from dementia assumed to be caused by epilepsy. She died at the hospital on January 6, 1893. Patient number 53 was Nickolas Sewell, one of the first African American patients admitted. Sewell was a resident of Washington who lived in the West Lodge until his death in 1906. A 1905 note in his file stated, "There has been no change in this man's condition in years . . . has some harmless delusions. He was one of the first patients admitted to this Hospital March 12th 1855."

Long-term patients like Sewell and Hall, along with changing admission categories that allowed more patients, contributed to overcrowding. This was a problem that plagued the hospital well into the 20th century. Dayrooms and corridors served as bedrooms, and rooms intended for one patient were often occupied by three. In 1877 there were 770 patients, but the hospital could comfortably house only 563. In his annual report that year, Dr. Nichols pleaded with the government that it owed proper accommodations to the many veterans living at the hospital. "Duty to the defenders of the country suffering from the most grievous affliction to which flesh is heir, and to the poor insane of the seat of the National Government suffering from a like affliction, to whose care the country is pledged by several statutes and the practice of more than a quarter of a century, proper pride in the standing and influence, and justice to the persons intrusted [sic] with the arduous responsibilities of its administration, require that the improvement contemplated by this estimate should be undertaken with the least practicable delay." His appeal was unsuccessful.

In the early 1870s, two additions to the male side of the Center Building had been built but quickly became inadequate to meet the hospital's needs. In 1875, Nichols proposed building a separate facility with its own grounds for female patients. At the time, the movements of both sexes outside the Center Building were restricted as efforts were made to keep them separate. Because of the greater number of male patients, the outdoor areas females were allowed to exercise in and enjoy were greatly reduced. The perfect setting for a women's hospital, Nichols believed, was across the public road that passed the hospital. Plans for the new building had already been drawn up by Architect of the Capitol Edward Clark. The three-story structure would have housed women in dormitories and single rooms. It was never built. Two years following his request, Nichols left the hospital after 25 years and returned to New York to run the Bloomingdale Asylum.

Following Nichols's departure for New York, Dr. William Whitney Godding became superintendent. Godding had more success than his predecessor with building new patient residences. Nearly every year of the 22 years Godding led the institution, a new building was under construction. Where Nichols had added on to the Center Building the few times he had been successful in appropriating funds, Godding built "detached buildings," as he called them. Following his death in 1899, an enormous building campaign was initiated by his successor, Dr. Alonzo Richardson. Eleven patient buildings were built, and the hospital expanded to the east side of the public road. The new section of the hospital became known as the East Campus and the older, the West Campus. According to available records, Bryan Hall primarily lived in the Center Building in wards that included other paying patients. He also resided in the Relief Building, one of the first of Godding's detached buildings erected with the small congressional appropriation for their construction. Toward the end of his life, Hall was treated in R Building, one of the new buildings on the East Campus. Hall's file only includes notations of where he resided beginning in the mid-1880s.

Patient records, if they exist, offer a glimpse of a person's life, even if the file consists only of a single letter asking about an old friend, a discharge notice from the military, or a grandchild checking to see if the grandfather they never met really had been a patient at the hospital. Letters were often addressed to the superintendent, and he was often the one who responded. Beginning in the early 20th century, when White became superintendent, more detailed records, including individual medical histories, were collected. Some 19th-century patient files are more detailed than others and contain a good bit of correspondence and information on an individual’s life at the hospital. Bryan Hall's file, prior to White's arrival, provides details of his stay in letters. For other patients, however, the first notations on their condition begin years or decades after their admittance. Patient Susan Spalding is one example. A note in her file states, "This patient was admitted August 12, 1861. Physician's notes began in 1903."

According to Bryan Hall's record, he read a great deal and amassed a large number of newspapers in his room. He wore a collar and tie every day, which an attendant helped him to put on. Hall ate breakfast in his room instead of with other patients, and he delivered newspapers at the hospital for a time. It was remarked that his sense of humor could be embarrassing for others. On one occasion, while outside on the grounds, he saw an attendant and remarked loudly, "There goes one of the ugliest men in Washington." Hall's file is three folders thick. It includes letters, charts, and notes by physicians.

To protect privacy, only patient files that are 75 years or older are available to the public, and not all patient files were retained. The files examined for this article were more observational in terms of the patient's health than deeply personal, though one may consider reading someone else's letters or a nurse's description of a patient's habits, hygiene, or day to day life as an intrusion into another's private information.

The first patient record available belongs to the third person admitted to the institution, Robert A. Hawke. The ward notes reveal that he had parole, often meaning freedom to enjoy the hospital's grounds. Patients were frequently accompanied by attendants while outside, but some patients were allowed to leave the grounds unattended. Hawke primarily lived in the Center Building but was transferred to the Toner Building, an infirmary built in 1889, where he "died very easy at 3:40PM 6-14-07." Following his death, a cousin wrote expressing sadness and guilt over both the death and not being able to afford to collect the body personally.

Hall, like Hawke, had parole and seems to have enjoyed a great amount of freedom. For 12 years he worked on the hospital trade wagon, which often required daily trips to the city to pick up groceries and other items. On Sundays he worshipped at St. Mark's Church on Capitol Hill. Hall often ventured without an attendant into Washington, where he sometimes went to the theater. In 1921 he was hit by a streetcar while returning from a trip to the city and fractured his leg. Hall enjoyed baseball games and visited friends in Richmond, Virginia, and family in New York. In 1876 his father wrote to Dr. Nichols to see if it was possible for Bryan to travel to the Centennial, presumably the celebration held in Philadelphia, and in 1893 he asked if Bryan could attend the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Whether Bryan attended either is unclear, but on October 2, 1893, he was away from the hospital and wrote to his doctor, "Dr. Witmer, I have $30 over and may stop over Chicago day on Oct 9th and again I may be back next Saturday. Yours truly, BH Hall." If Hall had been at the exposition on the ninth, he would have been one of over 700,000 people who attended and marked the anniversary of the city's 1871 fire on Chicago Day.

Family and friends wrote to Bryan and often to the superintendent to inquire about his health. They wanted to express their appreciation for the good care he received and to know if there was any improvement. His sister wrote in 1921, "I know from my own hospital years that patients' families are sometimes more troublesome than patients. Be assured this member of one appreciates your care of our handicapped relative." Relatives visited and sent him a bike for Christmas, magazine subscriptions, and clothes. His stepmother wrote to ask if she could send a reading lamp, but did not want to interfere with hospital policies by doing so. Reverend Hall wrote to check on an attendant Bryan said was mistreating him. One family friend inquired about which sports would be appropriate for Bryan. "We asked many questions last spring about lawn tennis. That seems to me a complicated game and to require many companions. . . . Archery might be just the thing, if you pronounce it safe." Following Hall's death in 1923, his sister wrote to his doctors concerning his belongings, the funeral held at St. Mark's, and to share, "Bryan's body lies at the foot of my father's grave, a place I have always kept for him."

Hall's file and St. Elizabeths' records were acquired by the National Archives in the 1970s. Archives staff first examined the institution's historic materials in the 1930s. The collection provides a wealth of information on the hospital but tells only part of the institution's history. Some of the first indications of the vast amount of material saved by the hospital come from reports written by Oliver W. Holmes and Herman Kahn, who went to St. Elizabeths in 1938 to assess its historic material.

Holmes and Kahn found over 2,332 linear feet of records covering all aspects of St. Elizabeths' history from its inception up to 1938, when they visited the hospital. The records were kept in at least five different locations. Some were stored in a systematic manner, while others were kept "in generally unsuitable quarters and subject to dust and fire" or in "five large barrels crammed full of records which have been flung into it in a helter-skelter manner." Kahn did not recommend that any of the files he studied during this preliminary assessment be transferred to the National Archives, while Holmes suggested acquiring only 60 linear feet of records. This represents a little less than 4 percent of the records Holmes examined, but it appears to be the core of the holdings on the administration of the hospital. Holmes noted in his 1938 report that the hospital "is rather proud of its older records and I believe the matter of transfer might well rest until it is suggested by them. Meantime, the records will be open to legitimate inquirers."

The National Archives officially acquired the records in 1973. In early 1968, Dr. David Musto, a special assistant to the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, began working with the hospital staff to provide a safe and central location for the records that remained there. He stated in a letter to the acting superintendent, Dr. David Harris, that he believed "St. Elizabeths may become the first mental hospital to fully organize its records for the benefit of social historians." Correspondence from this period indicates that the hospital collected and took inventory of the majority of the records that remained on campus. St. Elizabeths established a Committee on Historical Material, which worked with NIMH and the National Archives to turn over the records.

Charles Dewing, a records appraisal specialist, met with then Superintendent Dr. Luther Robinson and staff members at length to go over which records would be of interest to the Archives. It was decided in an agreement with the National Archives that only a sampling of patient case files from 1900 forward would be kept as permanent records. Starting with the year 1900, the samples would consist of case files of patients admitted to the hospital in years divisible by five (1900, 1905, 1910, etc.). Dewing assembled 120 cubic feet of material for transfer. Many historic items that remained at the hospital were put on display in St. Elizabeths’ museum, which operated for nearly 20 years, but closed in the mid-1990s. The hospital recently opened a new museum in which historic photographs, furniture, and artifacts highlight St. Elizabeths' 155 years in operation.

The records of St. Elizabeths Hospital provide a glimpse into the operation of a historic hospital and the lives of people who passed through its doors. In the thousands of pages of documents, there are countless lives to discover and stories to be told.

Frances M. McMillen earned her master’s degree in architectural history from the University of Virginia in 2008. She is currently working as a historian in Washington, D.C.

James S. Kane serves on the Historic Preservation Review Board for the District of Columbia and works for a construction firm whose expertise includes historic preservation projects.

Note on Sources

Record Group 418, Records of St. Elizabeths Hospital, provided a great deal of the source material for this article. Several other collections at the National Archives have information on St. Elizabeths, including Record Group 48, Records of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior; Record Group 90, Records of the Public Health Service; and Record Group 66, Records of the Commission of Fine Arts. Archivist Bill Creech, who oversees Record Group 418, provided background on the organization and acquisition of the collection, as well as spent much appreciated time talking about the records during the writing of this article.

The bulk of the information on the development and early history of the hospital was compiled during the writing of Frances McMillen's master's thesis, "Ministering to a Mind Diseased: Landscape, Architecture and Moral Treatment at St. Elizabeths Hospital, 1852–1905" (University of Virginia, 2008). Drs. Suryabala Kanhouwa and Jogues Prandoni, and Velora Jernigan-Pedrick, and the hospital library keep St. Elizabeths' history alive and were wonderful resources.

Secondary sources that provided invaluable information on the hospital, architectural history of American mental institutions, and the history of mental health care include Frank Millikan's "Wards of the Nation: The Making of St. Elizabeths Hospital, 1852–1920" (Ph.D. diss., George Washington University, 1989); Carla Yanni's The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); and Gerald Grob's Mental Institutions in America: Social Policy in America to 1875 (New York: Free Press, 1973); The Mad Among Us: A History of the Care of America's Mentally Ill (New York: Free Press, 1994); and Mental Illness and American Society, 1875–1940 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983). In addition to the collections at the National Archives, St. Elizabeths' annual reports, historic newspapers, and congressional documents were valuable sources of material.