Smugglers, Bootleggers, Scofflaws

How Liquor Got into New York City during Prohibition

Fall 2011, Vol. 43, No. 3

By Ellen NicKenzie Lawson

© 2011 by Ellen NicKenzie Lawson

“New York City, as the greatest liquor market in the United States, is a great temptation for the rum runners,” wrote a Coast Guard intelligence officer in 1927 in the midst of Prohibition.

The nation’s largest city never “dried up,” despite the 18th amendment to the Constitution, which took effect in 1920 and banned the production, transportation, or sale of liquor for pleasure, because New York’s smugglers, bootleggers, and scofflaws defied the national liquor ban.

A unique and extensive database of information and photographs on liquor smuggling and New York City exists in the National Archives among 90 boxes of Coast Guard Seized Vessel records for the years 1920–1933.

Examining the history of smuggling to the nation’s largest liquor market during Prohibition helps to understand why this market would not be suppressed. Smuggling contributed to the rise of the earliest liquor syndicates controlled by bootleggers, and the city’s immigrant and urban culture encouraged drinking at home and in nightclubs and speakeasies by hundreds of thousands of scofflaws.

Ultimately, New Yorkers were the driving force in the national movement to repeal the 18th amendment, the only Constitutional amendment ever repealed.

The general history of Rum Row, where liquor supply ships were located off major coastal cities, is fairly well known. At first the “Rows” were 3 miles from shore, but the patrolled area was moved to 12 miles in 1924.

New York’s Rum Row, the largest on either coast, was southeast of Nantucket Island and east of Long Island. Here ships from Europe, the West Indies, and Canada met American contact boats coming out from shore. The liquor was then smuggled directly to the city or via landing sites on Long Island or New Jersey, or even from the distant South or New England.

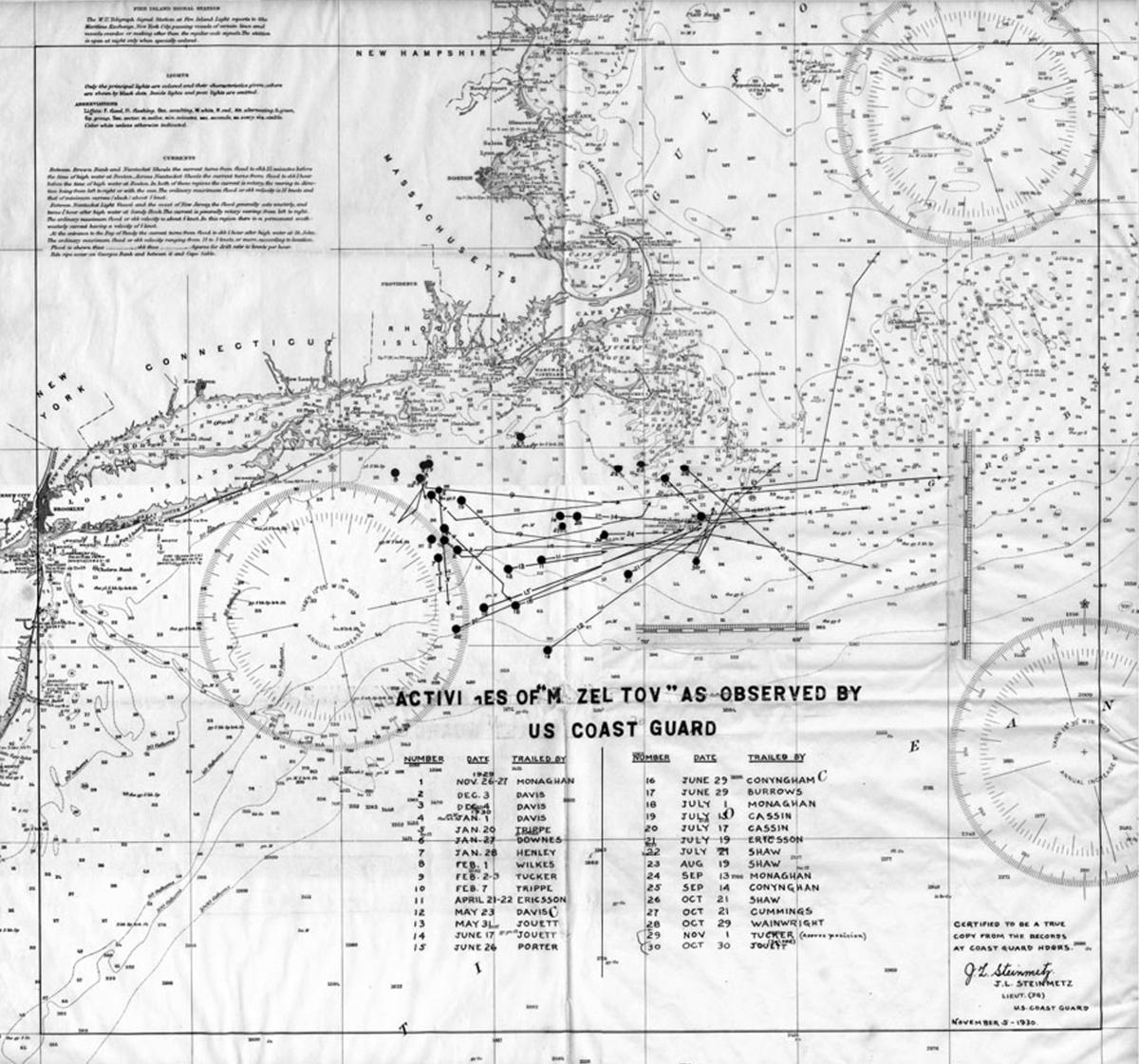

A rare nautical chart in the National Archives delineates the geography of New York’s Rum Row by documenting Coast Guard observations of the Mazel Tov for a year before it was seized for straying within the legal limit.

Hundreds of sea captains were smugglers, but few are known to the historical record. The most well known was and remains Capt. Bill McCoy, born in New York State and trained in the merchant marine. His biography, published at the end of Prohibition, cashed in on the public’s belief that the liquor he smuggled was the best in quality, the “real McCoy.”

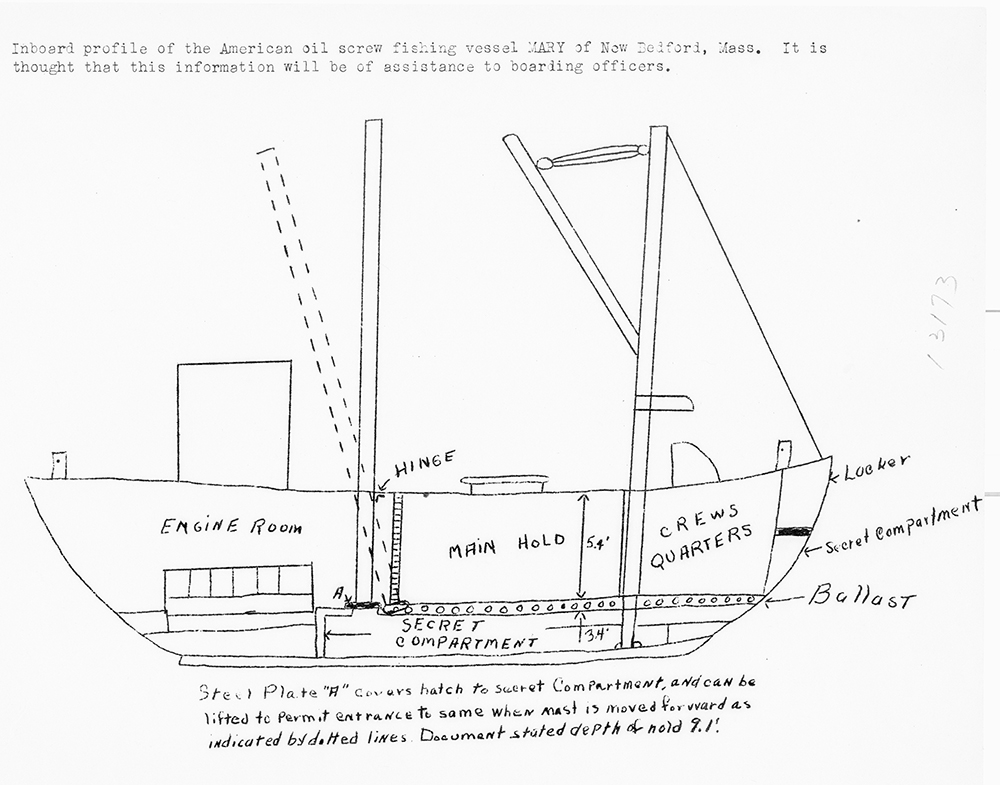

Smuggled liquor came ashore on tugs, barges, yachts, tankers, liners, and speedboats; some were not even seaworthy. Even a submarine or two may have been used, albeit briefly, in 1924, when newspapers reported rumors that submarines were supplying the Jersey shore and Cape Cod. A smuggler also once testified in court that he saw a submarine with a European crew surface on Rum Row.

And an aerial photograph among previously classified Coast Guard intelligence records purports to document two non-naval submarines below the Hudson River.

Life on Rum Row: A Nautical Wild West

Until the Coast Guard acquired destroyers from the Navy to patrol Rum Row in the mid-1920s, the area was like the Wild West with its violence, piracy, and hijackings. One ship with $700,000 of liquor was pirated by New Yorkers who learned it would be waiting on Rum Row while the quality of its liquor was being checked on shore. Later, London Schooners Association‘s investigation concluded that it was actually an insurance scam.

When a foreign agent arrived in Manhattan to take orders for liquor, he was wined and dined on Broadway while 24 armed New Yorkers plundered his ship on Rum Row under the direction of a man named “Eddie,” who confided to Captain McCoy that the gang resented foreigners muscling in on their turf. (The sole casualty in this piracy was Eddie, whose body was thrown overboard on the last return boat.)

No one will ever know how many New Yorkers died aboard contact ships that sank at sea, but the Coast Guard learned about two instances from grieving wives, siblings, and mothers.

Agnes McArdle’s brother and 11 others died when their tug, captained by a former Manhattan policeman, sank in a storm. She claimed that a Brooklyn man, the ship’s owner, had lost an earlier rum ship, too, and she wanted him arrested because he refused to honor life insurance claims from the sailors’ families yet lived “in luxury” himself.

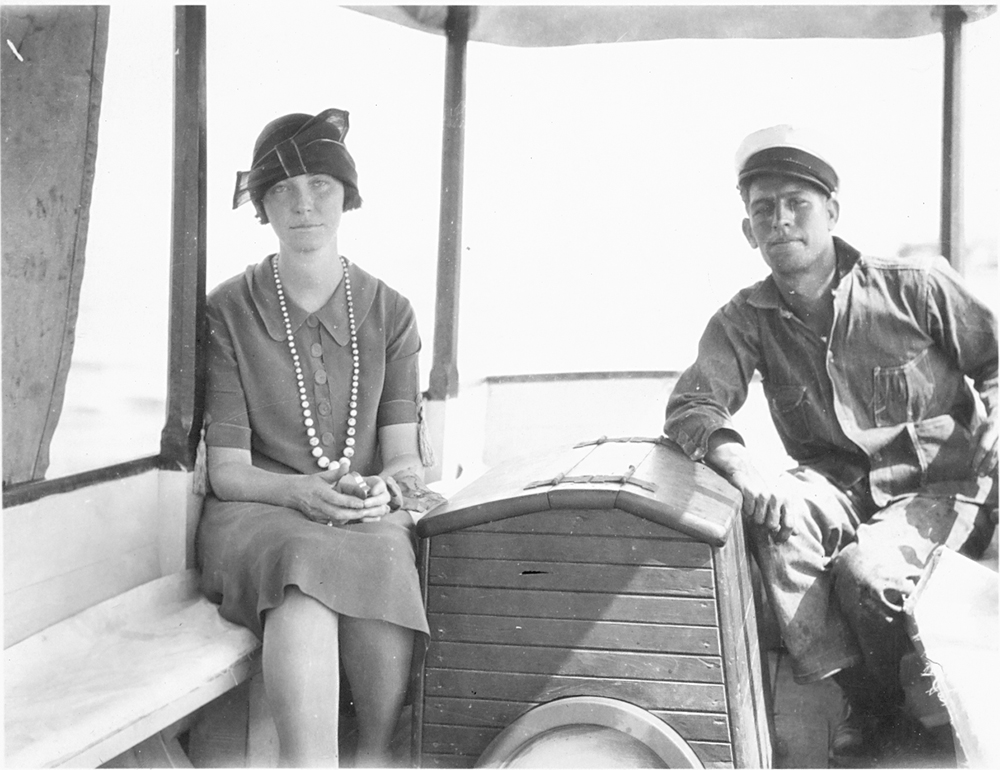

Women lived on Rum Row as cooks or wives or guests of captains. MCoy even claimed that a boatload of Manhattan prostitutes ventured out one summer. According to reporters, the Queen of Rum Row was American Gertrude Lythgoe, who stayed at the Waldorf-Astoria after weeks on McCoy’s ship selling quality liquor for her London-based company. McCoy had taken her there after male wholesalers squeezed her out of the market in Nassau.

Rum Row was high-tech for the time; by the end of the twenties, smugglers used new technology like radios and airplanes. The Coast Guard had a crack radio unit in Manhattan for locating land stations and intercepting and decoding messages from Rum Row, some of these were reputedly more complicated and harder to decipher than codes used in World War II.

The agency also monitored airplanes above Rum Row, some of which dropped messages to ships below in bottles. Seaplanes also landed alongside the ships and loaded cases of liquor. When one seaplane’s engine failed, it was captured and hauled all the way back to New York Harbor. William Bell Atwater, who had been in charge of U.S. Naval Air Forces in Italy during World War I, was charged with stealing a plane from New York’s Curtis Air Field to fetch alcohol from Rum Row.

Smugglers, Coast Guard Play Cat and Mouse

Manhattan was the goal of most smugglers, although traffic was diverted at times to Long Island and New Jersey and trucked to the city. A smuggler who made it into New York Harbor could then access Manhattan’s 20 miles of shoreline for a good landing site. By day, smugglers mingled in the harbor among the extensive traffic of ships, yachts, fishing boats, and ferries. At night, smugglers would sneak into the harbor by running through the Narrows and up the rivers with all their lights off.

Ocean liners and steamers smuggled liquor directly to Manhattan. As liners slowed down, preparatory to docking, passengers and crew sometimes passed liquor cases overboard to men in trailing speedboats. An elegant Park Avenue nightclub hostess claimed the captain of a French liner regularly smuggled her best wines. Musicians, butchers, second cooks, and confectioners on one German liner were implicated in smuggling liquor. And one undercover operation, directed from Washington because customs officials in Manhattan were too corrupt, exposed smuggling by the British Royal London Mail Steamer Packet.

Foreign ships smuggling liquor into the harbor violated American law, but those that remained on Rum Row were protected by international treaty. In 1924, a treaty between the United States, Canada, and Britain specified that the U.S. Coast Guard could search suspicious vessels that were “one hour's distance” from shore—12 miles in a day when most large ships could go no faster than 12 miles an hour.

The Coast Guard, interpreting the treaty to refer to speedboats that could go up to 40 miles an hour then, seized several foreign ships more than 20 miles at sea. One of these was a Norwegian ship whose captain was ordered to sail into New York Harbor, where his crew was imprisoned on Ellis Island and then deported. (The Norwegians eventually won in court, and the U.S. Congress voted reparations for captain and crew over a decade later.)

The Statue of Liberty ruled New York Harbor even during Prohibition, when Americans were not at liberty to drink. The Coast Guard and U.S. Customs anchored large rum ships near Liberty Island (then called Bedloes).

One striking photograph in the National Archives shows a freshly painted, sleek, low-lying yacht with the Statue of Liberty in the background. The smugglers on this vessel had boldly cruised into the harbor by daylight dressed in yachting whites, sitting in wicker furniture on deck, leisurely smoking Havana cigars, and being served afternoon tea by liveried servants—the perfect cover, they thought.

Guardsmen, watching through telescopes from a nearby cutter, observed the hands holding those cigars were rough and dirty like the hands of longshoremen, not leisured yachtsmen. The yacht was also riding extremely low in the water as if it carried a heavy load.

Smugglers also went up the Hudson River (North River) to land liquor. The Manhattan owner of Kennedy’s Chop House on 121 West 45th Street was suspected of smuggling up the river to a Kingston warehouse and then later having the liquor trucked back to Manhattan.

(The upriver site was known as Kennedy’s Warehouse and may have contributed to later rumors that it was owned by Joseph P. Kennedy, father of the future President, who was working as an investment banker in New York City in the 1920s.)

The body of 25-year-old Edwin J. Kennedy was found wrapped in a comforter floating in the Hudson off West 84th Street in 1927; he had been shot in the head. Robbery was not the motive as a pawn ticket, a diamond ring, and $210 in case were in his pockets. His older brother Jack, owner of the Chop House, insisted Edwin had no enemies and was in excellent spirits before his disappearance. His widow told police, “I feel in my heart that he was killed by bootleggers. Which one or ones I cannot say.” The Coast Guard, based on its suspicions of smuggling activity in Kingston, could do little to solve this case, although the agency believed the widow was right.

Hudson and East Rivers Provide Avenues for Liquor Trafficking

A legal battle over ownership of the Hudson River occurred during Prohibition when a rum ship was seized at a Hoboken dock and charges were brought in New Jersey courts. While agreeing that New York State and New Jersey jointly owned the river’s bottom, the defense argued that, based on an obscure antebellum case, New York owned the river and charges should be dropped because New Jersey lacked jurisdiction. The friendly judge agreed and dismissed the case.

The U.S. Department of Justice appealed, stating that the boundaries of the two states had been established in the late 18th century, each owning half the river. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually agreed, but until then, smugglers chased in New York Harbor could head for sanctuary at New Jersey docks and count on a friendly judge’s interpretation of an obscure law.

The East River was also popular with smugglers. When officials at Sun Oil suspected their East Coast tankers were picking up liquor on Rum Row, the company alerted authorities. Soon thereafter, customs officers trailed a tanker entering New York Harbor at a discreet distance up the Hudson, then followed it as it made a U-turn back to the harbor and up the East River to Brooklyn, where 60 longshoremen began unloading the liquor.

As 75 customs agents approached, the longshoremen mistook them for a rival gang and began firing. When they realized the newcomers were federal agents, they tossed their guns into the water so they would not be prosecuted for violating New York’s Sullivan gun law. Most of the longshoremen gave legitimate names when arrested, and many were German, Jewish, French, or Italian ones. A few gave the family name as Doe, including William (“Scottie”) Doe, James (“Big Walter”) Doe, Raynond (“Sparks”) Doe, and Ralph (“Captain Ralph”) Doe. Authorities knew the “Does” were from Augie Pisano’s gang, which handled European liquor landed in Brooklyn and destined for Al Capone in Chicago. (“Captain Ralph Dow” was probably Capone’s older brother, who sometimes visited New York to oversee such shipments.)

Fulton Fish Market, located on the lower Manhattan side of the East River, was popular with smugglers because it was closed at night, and docks and unloading facilities were accessible. Custom’s Deputy Surveyor John McGill, head of the New York harbor patrol, joked that he would catch smugglers after seeing the vessels’ names in his dreams. On the other hand, New York Coast Guard Commander A. J. Henderson grimly argued that the Coast Guard was hampered in enforcement because customs was not strenuously policing Fulton Market. Eventually McGill’s staff was tripled to 120 agents, and he relied less on dreams and more on his agents.

The Bronx shoreline on the East River is minimal, but the largest smuggling fleet for the entire metropolis was located in this borough in a marina near Hell Gate Bridge. This was a good location because contact boats could either travel down the East River, through the harbor, and then out to sea, or venture through the turbulent waters of Hell Gate and through Long Island Sound and then out to Rum Row. One hundred rum speedboats and larrger craft docked here, including one disguised as a Coast Guard cutter, which escorted other boats as if they had been captured and were being taken to shore to be booked.

A Neighborhood of Captains and Seafaring Smugglers

With contact boats coming into the harbor and up the two rivers, the Coast Guard decided to semi-blockade New York Harbor for weeks at a time even though it was the nation’s biggest port. The agency monitored vessels waiting outside the Narrows against the names of known rumrunners.

Some rum captains changed the names on their vessels’ sterns and smokestacks to those of legitimate ships to sneak into the harbor, but the Coast Guard became wise to this and seized such ships in the Narrows. One ship, released on bond, was soon outside the harbor with another load of liquor.

“What is $7,500 [bond] to that ring?” complained one Coast Guard officer. “I look upon the release as a betrayal of the forces of the Federal Government.” He felt as if he and his men were “jousting at windmills.”

Smugglers captured at sea were booked at the Customs Bureau’s barge office at the foot of Whitehall Street, adjacent to the ferry terminals at the southernmost tip of Manhattan. Many sailors deliberately got drunk and could not be interrogated until they sobered up, giving lawyers for the liquor syndicates time to get them out on bail.

Seafaring men have lived on or near South Street on the East River since the 17th century. Capt. Browne-Willis, known as “Whiskers” because of his “Prince Albert Beard,” lodged at 2 Fulton Street during Prohibition. Caught smuggling in New York Harbor on his 13th trip, he and his sailors testified that there was liquor aboard, but it was never intended for Manhattan.

Another Manhattan-based captain named George Jeffries was caught after he had made 40 successful liquor trips into the harbor. Most captains were reluctant to talk to authorities, but Jeffries hoped to mitigate his sentence and gave them the names of all the gangsters for whom he smuggled and offered to show the different sites where he dropped off the liquor. Authorities did not follow up because they feared any action would imperil his life. Jeffries said all monetary transactions were from a midtown office on Broadway whose address he could not recall. A search of his luggage produced a calling card belonging to Nookie Collins, “The Big Lobster Merchant,” specializing in “Skotch Tweed.” On the reverse the captain had carefully written in pencil “#1261 Broadway, Room 502,” with the notation “Get off [at] 34th Street.”

Besides captains, rum sailors lived on the city’s waterfronts, including at the Seaman’s Church Institute on 25 South Street. Pay on rum ships was higher than on law-aiding vessels, and there was usually free liquor. Sometimes those who could not be induced with money or liquor were tricked or shanghaied into service.

The Coast Guard rescued four such sailors from a ship on Rum Row after spotting a blanket they held up on deck as a sign of distress. One cook based in New York signed on to work on a barge headed for the Caribbean only to discover that the barge was first going to Nova Scotia to pick up liquor to resell along the American coast. When the ship arrived in Nassau, he went to the American consulate to lodge a complaint, saying he had been intimidated into staying aboard and that the captain kept an arsenal of 10 pistols and 8 rifles.

Liquor Syndicates Move In as Federal Agents Crack Down

Every American knows Prohibition contributed to the growth of the American underworld, but few know exactly how this happened. New York City had large ethnic gangs long before 1920, but gangs became better organized and very wealthy in the twenties by focusing on the black market in liquor.

The Lower East Side’s earliest liquor-smuggling syndicate was operated by “Waxey” Gordon (Irving Wexler), a former pickpocket and labor “thug.” Arnold Rothstein, black sheep of an Upper West Side second-generation German-Jewish family in the garment industry, bankrolled the purchase of liquor abroad, the hiring of ships, and the bribing of a Coast Guard commander on the eastern end of Long Island so the shipments could be landed and trucked to Manhattan.

This system worked until the commander was replaced. Then Gordon and Rothstein had to divert a shipment to the West Indies, where the liquor was sold at cost. Rothstein, an investor with a reputation for only gambling on sure things such as the Black Sox World Series scandal, relinquished his role as a smuggler and left the entire operation to Gordon.

Gordon’s syndicate thrived until Capt. Hans Fuhrman, who operated a lumber barge and smuggled liquor for Gordon, was caught and agreed to testify against his boss. The captain died before the trial despite being protected in a guarded hotel room in the city. He was the only eyewitness. Police ruled this death a suicide, but his wife insisted that he was murdered. Gordon quit smuggling soon thereafter because he risked future conviction on the word of any one of his many captains. Instead, he owned and operated illegal domestic breweries and distilleries in New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. He was caught and convicted at the end of the era for income tax evasion based on information provided by rival gangsters.

Hell’s Kitchen stretched from West 23rd Street to the fifties and included extensive waterfront and railroad yards. Several pre-Prohibition Irish American gangs, like the Hudson Dusters and the Gophers, were located here. During Prohibition, William “Big Bill” Dwyer, a stevedore in the Longshoreman’s Union, emerged as leader of the West Side’s first successful liquor syndicate. Like Gordon on the East Side, Dwyer’s initial funding came from Rothstein. After Rothstein’s bodyguard, “Legs” Diamond, began hijacking Dwyer’s trucks, Dwyer stopped relying on Rothstein and turned to privacy to obtain his liquor. In 1923–1924, his gang relieved Rum Row of about a million and a half dollars worth of goods.

Dwyer was the next target after Gordon for the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York. Authorities learned from an engineer on a Canadian coal ship smuggling liquor to Fourth Street on the East River that the cargo belonged to Dwyer. The ship’s supercargo bragged to the engineer that Dwyer smuggled more liquor into New York than anyone else, using a corrupted Coast Guard patrol boat to escort ships into the harbor. Next, an undercover customs guard in a city speakeasy learned that another coal steamer would bring liquor up the Hudson. That steamer was seized, and 3,000 cases of liquor were found beneath hundreds of tons of coal. In the captain’s tally book for the liquor was the name and address of the Sea Grill Restaurant on West 45th Street, which Coast Guard intelligence believed was a Dwyer hangout.

More than 50 New Yorkers were identified as the Dwyer syndicate and tried, in two batches, for liquor conspiracy in 1926–1927. The first trial targeted Dwyer and high-level associates, but only Dwyer and his payoff agent were convicted by a sympathetic New York jury. After serving a year in prison, Dwyer, like Gordon and Rothstein earlier, concluded that direct smuggling was too risky. Dwyer became a silent partner in an illegal brewery in his old West Side neighborhood, which sold the city’s best quality beer, called “Madden No. 1” after West Side gangster and partner Owney Madden.

Despite Dwyer’s imprisonment, his syndicate continued because Frank Costello, misidentified as a less important underling in the second trial, benefited from a hung jury.. Costello later claimed privately that he bribed a juror. His records were conveniently "lost," and he was not retried.

The Dwyer/Costello syndicate rented warehouses along the North Atlantic in the Canadian maritime provinces and on the French islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, and operated a fleet of freighters bringing liquor to the warehouses from Canada and Europe. Costello managed this vast operation from a midtown Manhattan office, reputedly in the then-new Chrysler Building. He also continued Dwyer’s pattern of wholesale bribery of police, politicians, and federal agents. When one of his liquor supply ships sank after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic, Costello told a subordinate that it was too bad he couldn’t buy the iceberg.

Little Italy Syndicate Becomes Dominant Force in Smuggling

New York City’s third major liquor smuggling syndicate during Prohibition, like the Gordon and Dwyer/Costello operations, was also located in lower Manhattan. It was an Italian operation in Little Italy. Unione Sicilione’s chief, Joseph Masseria, an old-time boss called “Moustache Pete,” was not interested in smuggling but in continuing more traditional criminal activity like blackmail, robbery, and prostitution. Johnny Torrio and Al Capone, two New Yorkers who might have convinced Masseria to change to smuggling and bootlegging, moved to Chicago before Prohibition.

On a return visit to Little Italy, Capone challenged younger friends in the city to seize the day as he and Torrio were doing in Chicago. Two New Yorkers, Charles Luciano (Salvatore Lucania) and Joe Adonis (Joseph Doto) listened and began smuggling liquor with Masseria’s blessing, providing they remained loyal subordinates. Luciano and Adonis invited Costello (originally Castiglia but not Sicilian-born as they were) to join them as well as Meyer Lansky, who Luciano knew from his youth on the nearby Lower East Side. Lansky brought in Benjamin Siegel (“Bugsy”), and these two became the “muscle” for the new syndicate.

Like the Gordon and Dwyer syndicates, the new gang’s earliest financial backing came from Rothstein, who was on the lookout for promising ways to invest money. Rothstein suggested they market expensive liquor to rich New Yorkers instead of diluting it for a mass market.. The gang began by smuggling from the Bahamas and employed Captain McCoy. One of their first shipments directly from Europe was in a ship from the Azores hovering outside the Narrows. According to an FBI transcript of an interview with a Portuguese cook on that ship, the gang leaders personally went out in two speedboats to unload the liquor. Eventually they retreated into the background to run their growing operation, using others to fetch the liquor to shore.

This Little Italy syndicate dominated smuggling in New York City by the late 1920s after Gordon abandoned the field in 1925 and Dwyer was convicted in 1926. When Rothstein was murdered in 1928, the syndicate filled the power and money vacuum in the underworld left by his death. Two years later, the syndicate manipulated a power struggle within the mafia, between old world boss Masseria and recent Sicilian immigrant Salvatore Maranzano, in what was known in the underworld as the “Castellammare War.” (Maranzano was from Castellammare, Sicily.) Syndicate members were directly involved in Massaria’s murder in a deserted Coney Island restaurant and, through Lansky, for Maranzano’s murder by Jewish hit men disguised as federal tax agents.

By the end of Prohibition, Luciano, Adonis, Costello, Lansky, and Siegel were the core of the city’s increasingly powerful and rich underworld, which some historians have dubbed the Broadway Mob because they had relocated to midtown Manhattan near the theater district.

Before the emergence of the Broadway Mob, U.S. Attorney Emory Buckner was asked by a Senate committee in Washington to comment on the “foreign element” in bootlegging and smuggling in his Southern District of New York.

“I do not know, Senator,” he replied. “It is certainly not so marked that it has become a matter of such comment that it has reached me yet.” Yet by the 1930s, U.S. Attorney Thomas E. Dewey built a political reputation tackling this underworld, became governor of New York, and was the Republic presidential nominee in 1944 and 1948.

Ethnic Groups Helped to Repeal Prohibition

The word scofflaw was coined in a national contest during the twenties to describe Americans ignoring the 18th amendment. New York City had not only smuggling syndicates, illegal distilleries and breweries, and 50,000 families producing homemade liquor but also 500 nightclubs and an estimated 30,000 speakeasies. Scofflaws believed that by drinking they were striking a blow for individual liberties.

From the start, some New York City politicians opposed the 18th amendment. At first Fiorello La Guardia, the first Italian American congressman in American history, was a lone voice crying in the dry congressional wilderness. State Senator James J. Walker opposed ratification of the 18th amendment in the state legislature and later, and the popular Irish American mayor of the city in the twenties, thumbed his nose at the law.

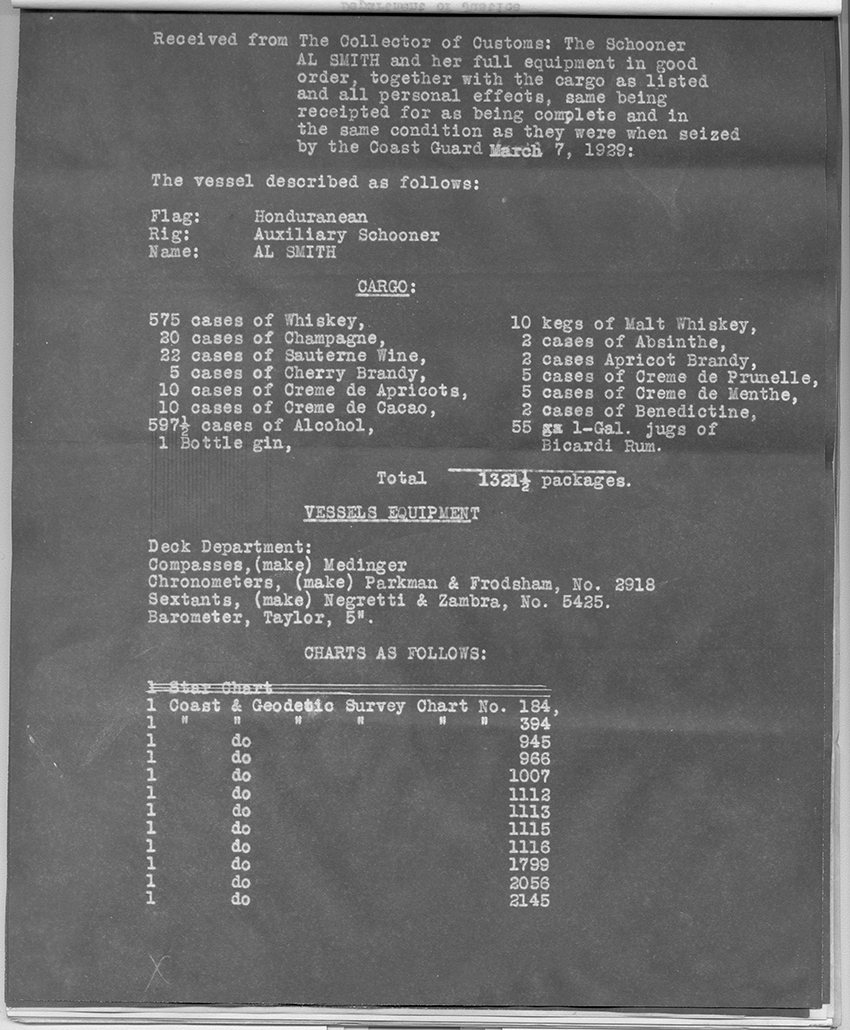

Governor Al Smith, raised on the Lower East Side, was the nation’s only wet candidate for President, nominated by the Democratic Party in 1928. (Smugglers honored him by naming a rumrunner after him.)

Why was New York City such a hotbed of opposition to Prohibition, with so many scofflaws, smugglers,and a Broadway Mob?

Mayor Walker once claimed that New York City in the twenties had more Irishmen than Dublin (400,000), more Italians than Rome (800,000), more Jews than Palestine (2 million), and more Germans (670,000) than any German city except Berlin.

These ethnic groups viewed the 18th amendment as an attack on their cultures, which did not condemn alcohol but celebrated it with Irish whiskey, German beer, and Italian dinner wines. In addition, for several hundreds of years in European history, the Irish and the Jews had made a living producing and selling liquor.

White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASP) Americans, those most ardently behind the 18th amendment, had their own historic tradition to lead them to support the 21st amendment.

Captain McCoy, presumably echoing the motivation of his fellow smugglers, claimed inspiration from John Hancock’s 18th-century defiance of the British Navigation Acts and antebellum abolitionists’ defiance of federal slave law in the 1850s. And it should not be forgotten that one possible derivation of the word Manhattan is the Native American word Manahachtanienk, which translates to “place of general inebriation.”

Ellen NicKenzie Lawson is a retired historian living in Colorado and has published articles on vessels seized by the Coast Guard during Prohibition off Cape Cod. She has a book manuscript based on the same body of records of New York City under consideration with an academic press. This article is a summary of that manuscript.

Note on Sources

Records consulted at the National Archives and Records Administration include Records of the United States Coast Guard, Record Group (RG) 26, Coast Guard Seized Vessels, Entry 179 A-1, and Coast Guard Intelligence Division, Entry 178; Records of the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, RG 10, National Commission on Prohibition, boxes 182, 199, 206–07; General Records of the Department of the Treasury, RG 56, Entry 191; and Records of the Internal Revenue Service, RG 58, Entry 231. Government publications included United States Senate, Proceedings of Subcommittee [on National Prohibition Law] of Committee on the Judiciary April, 1926; Official Records of the National Commission [Wickersham Commission] on Law Observance and Enforcement, 71st Congress, 3rd sess., S. Doc. 307 [1931]; and speeches by Fiorello La Guardia in the Congressional Record, 1920–1933.

Published primary sources relevant to this article include: Belle Livingston, Bell Out of Order (New York: Holt, 1959); Gertrudfe Lythgoe, The Bahama Queen: Autobiography of Gertrude “Cleo” Lythgoe (New York: Exposition Press, 1964); Carolyn Rothstein, Now I’ll Tell (New York: Vanguard Press, 1934); James Trager, ed., The New York Chronology (New York: HarperResource, 2003); Frederic E. Van de Water, The Real McCoy (Garden City, NY: Doubleday Doran and Co., 1931); Stanley Walker, The Night Club Era (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1933); Mabel Walker Willebrandt, The Inside of Prohibition (Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1929).

Relevant secondary sources include: Everett S. Allen, Black Ships: Rumrunners of Prohibition (Boston: Little, Brown, 1979); Herbert Asbury, The Great Illusion: An Informal History of Prohibition (New York: Greenwood Press, (1968 [reprint of 1950 edition]); T. J. English, Paddy Whacked: The Untold Story of the Irish-American Gangster (New York: Regan Books, 2005); Gene Fowler, Beau James: The Life & Times of Jimmy Walker (New York: Viking Press, 1949); Albert Fried, The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Gangster in America (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1980); Martin Gosch and Richard Hammet, The Last Testament of Lucky Luciano (Boston: Little Brown, 1974); Seymour M. Hersch, The Dark Side of Camelot (Boston: Little Brown, 1997); Kenneth T. Jackson, ed., The Encyclopedia of New York City (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995); Jenna Weissman Joselit, Our Gang: Jewish Crime and the New York Jewish Community, 1900–1940 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983); Matthew and Hannah Josephson, Al Smith: Hero of the Cities (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1969); Leonard Katz, Uncle Frank: The Biography of Frank Costello (New York: Drake Publishing, 1973); Leo Katcher, The Big Bankroll: The Life and Times of Arnold Rothstein (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994); Thomas Kessner, Fiorello H. La Guardia and the Making of Modern New York (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989).

Also James Lardner and Thomas Reppetto, NYPD: A City and Its Police (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2000); Michael Lerner, Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007); Martin Mayer, Emory Buckner (New York: Harper & Row, 1968); Hank Messik, Lansky (New York: Putnam, 1971); Herbert Mitgang, Once Upon a Time in New York: Jimmy Walker, Franklin Roosevelt, and the Last Great Battle of the Jazz Age (New York: Free Press, 2000); Humbert S. Nelli, The Business of Crime: Italians and Syndicate Crime in the United States (New York: Oxford Press, 1976); Virgil W. Peterson, The Mob: 200 Years of Organized Crime in New York (Ottawa, IL: Green Hill Publishers, 1983); Thomas A. Reppetto, American Mafia: A History of Its Rise to Power (New York: H. Holt, 2004); Giuseppe Selvaggi, tr. William A. Packer, The Rise of the Mafia in New York from 1896 through World War II (Indianapolis, IN, Bobbs-Merrill, 1978); Carl Sifakis, The Mafia Encyclopedia (New York: Facts on File, 1999); Craig Thompson and Allen Raymond, Gang Rule in New York (New York: Dial Press, 1940); George Walsh, Gentleman Jimmy Walker: Mayor of the Jazz Age (New York: Praeger, 1974); Malcolm E. Willoughby, Rum War at Sea (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964); George Wolf, with Joseph DiMona, Frank Costello: Prime Minister of the Underworld (New York: Morrow, 1974); and Howard Zinn, La Guardia in Congress (Westport, CT: Norton, 1969).