The Mystery of the Sinking of the Royal T. Frank

Winter 2012, Vol. 44, No. 4

By Peter von Buol

© 2012 by Peter von Buol

As a child growing up on Maui, Ramona Ho heard her father, Joseph Cabral, tell stories about the day he and his classmates helped rescue 33 survivors from the Royal T. Frank, a U.S. Army transport ship sunk by a Japanese torpedo off Maui’s beautiful Hana Coast in January 1942.

Surprisingly, it was a story no one else seemed to remember. And even today, the sinking of the Royal T. Frank remains one of the mysteries from World War II.

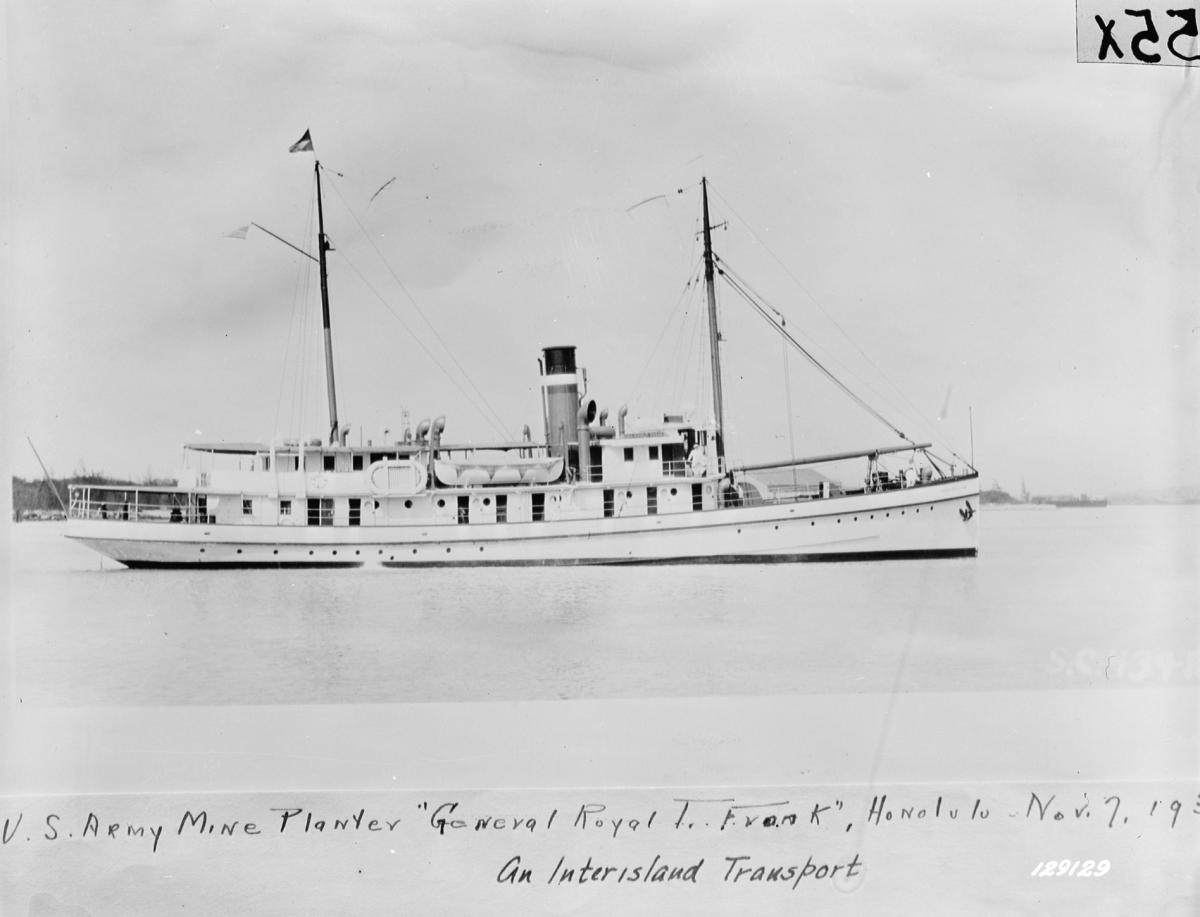

Before the outbreak of the Second World War, the Royal T. Frank had been used to transport military personnel to the island of Hawaii (the Big Island) and Maui, many of whom went on excursions to visit Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. In the months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, however, its mission changed to transporting new recruits and ammunition, according to Tricia Marciel, granddaughter of Walter C. Wiechert, the ship’s last captain.

The Royal T. Frank’s final voyage occurred in a particularly tense time period in Hawaii. Japanese submarines were active in Hawaiian waters and had already sunk three ships. A submarine had also surfaced to shell Maui’s Kahului Harbor, and others had fired at Hilo on the Big Island and Nawiliwili Harbor on Kauai. As a precaution, on its final voyage, the Royal T. Frank was part of a three-ship convoy that included a Navy destroyer.

Aboard were 26 soldiers from the Big Island who had just completed boot camp at Schofield Barracks on Oahu.

According to now-declassified government documents, a Japanese submarine fired on the transport just after seven o'clock on the morning of January 28, 1942, an estimated 30 miles north of the Big Island’s Upolu Point in the Alenuihāhā Channel. Two earlier torpedoes had missed.

The Official Account: Ship Sank in a Minute

An official account given by one of the ship’s officers and published in mainland newspapers (which were not subject to Hawaii’s martial law), states that the third torpedo had moved deceptively slowly prior to impact.

“I saw a torpedo coming straight at us. It veered as it approached. It appeared to be moving very slowly and seemed to be running down. It struck opposite the starboard boiler. There was a terrific explosion. As soon as I had seen the wake [of the torpedo], I ran forward shouting ‘torpedo!’” said the unnamed officer in an official account released by U.S. Army authorities and reported by the New York Times on February 11, 1942.

Those below deck were killed by the initial explosion. Above deck, flying shrapnel killed Captain Wiechert and others, and the ship sank in less than a minute. Of the 60 people aboard the Frank, only 36 survived. Survivors of the explosion included nine of the Big Island soldiers who had been above deck and 27 crew members. Some were thrown into the water, and others jumped in soon afterwards. Covered in oil, the survivors spent hours in the ocean, many clinging to whatever debris they could, before they were picked up by the ammunition barge that had been the actual target of the Japanese submarine.

“My father had told us the story since we were very little,” says Ho. “The survivors had come ashore while Dad was at school. . . . [Most were] covered with oil and were naked.” Drilled for just such an incident by their principal, William P. Haia, the students hurried the men to the school, helped them clean up, and assembled cots for them. The Navy flew in a medic to treat them until an ambulance could traverse the winding Hana road to bring the men out. A day later, the survivors were gone—and soon, so was the story.

For decades after the war, the story of what had happened to the Royal T. Frank remained unknown to most. Marciel and her family believe the secrecy may have been because there is a chance the ship had been on a top-secret mission. Her grandfather, even before the attack on Pearl Harbor, had expressed concerns about the inter-island trips to his wife.

On November 28, 1941, Adm. Husband E. Kimmel, the commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet, had issued orders to “bomb on contact” any foreign submarines and had relayed the information to Adm. Harold Rainsford Stark, the Navy’s chief of naval operations.

“You will note that I have issued orders to the Pacific Fleet to depth bomb all submarine contacts in the Oahu operating area,” wrote Kimmel to Stark.

In the years before America’s entry into the Second World War, said Marciel, the Royal T. Frank had been primarily used to transport soldiers to the islands of Hawaii and Maui for recreational purposes. In the months leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor, its mission had suddenly changed.

“It was being used to transport new recruits and ammunition. Apparently, my grandfather had a very ominous feeling about this last voyage—he felt something was going to happen. He had seemed to know about Japanese submarines in the water, even before Pearl Harbor. My mother mentioned he even had written a letter to President Roosevelt addressing his concerns about being followed and also about the dangers of what they were transporting,” said Marciel.

The low profile of the Royal T. Frank would have made it difficult to be seen by Japanese submarines, and Stark had urged Kimmel to employ small surface vessels as lookouts.

Portentously, prior to his last voyage, Marciel’s grandfather had left his personal possessions, including his wedding ring, at home. While the families of the new recruits lost in the explosion were not told about the cause of death, Wiechert’s widow was in-formed of the sinking.

“My mother’s assumption is the top-secret nature of the trip is probably why the families of those soldiers that perished were not told about it until after the war. My grandmother, however, who at the time was seven months pregnant with my mother, learned my grandfather was missing approximately six weeks after his ship had gone down,” said Marciel.

In the 1980s, while a student the University of Hawaii-Manoa on Oahu, Ramona Ho started to research the story her father had told her. Initially, she could not find out anything about what had happened.

“The only way I could find out anything about the incident was through the name of the vessel, the Royal T. Frank,” says Ho.

Survivor Haruo Yamashita, who died in early 2012, told the mainland-based Go for Broke Foundation in an interview recorded in 2010 that the vessel had been on its way to the Big Island’s Kawaihae Harbor to pick up more troops when it was hit. Along with Yamashita, eight other Big Island soldiers survived and became known as the Torpedo Gang.

After the sinking, Yamashita and his comrades served throughout the duration of the war, and all survived. A close-knit group, they looked after one another afterwards. Each year, they would gather together to remember those who died that fateful day in 1942.

But for others, the Royal T. Frank sank from memory.

“My father said they were told by the military the incident never happened,” says Ho, “and they should ‘go home’ and not talk about it. My family didn’t talk. It was martial law and they all took it very seriously. Thousands of soldiers stationed around Maui, with guns and you obeyed. Hana, however, was very isolated. The fear was always that if the Japanese had landed in Hana, there would have been no defense.”

Kazuko Ushijima of Hilo says her late husband, Torpedo Gang member Shigeru “Rueben” Ushijima, was also told not to mention the incident.

“They just didn’t talk about it to [others outside their group] until after the war,” says Ushijima.

Shigeru had taken a group photograph of the other 25 Big Island soldiers at Schofield Barracks just two days prior to the sinking. Though his camera didn’t survive the sinking, the image miraculously did; a soldier who was not aboard the vessel had taken the film to be developed.

Seven decades later, a mystery remains: despite advances in technology, the wreck of the Royal T. Frank has never been found.

“It is believed to be in water too deep,” says Oahu-based shipwreck researcher and author Richard Rogers, “and there is not a very detailed idea of where she was torpedoed.” Rogers says that if a report from the Japanese submarine exists and is ever located, there might yet “be enough data to begin a survey with pretty pricey gadgets.”

The Japanese submarine that had sunk the Royal T. Frank was itself sunk with all hands off the island of Bougainville in New Guinea by American depth charges on February 1, 1944, as the U.S. military and its allies were pushing their way to the Japanese mainland, island by island.

Peter von Buol is an adjunct professor of journalism at Columbia College-Chicago. Since childhood, he has been interested in the history of Hawaii and the Pacific. As a freelance journalist, he frequently writes about Hawaiian history and Hawaii’s unique wildlife. He is also a docent at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History in its Pacific Halls.

Note on Sources

The report about the sinking of the Royal T. Frank is among the records of the Adjutant General’s Office Classified Decimal Files, AG 579.14 (subsection: project files; nautical). The records were originally stamped “Secret.”

Kimmel refers to the order to “bomb on contact” any foreign submarines in Kimmel to “Betty” [Admiral Stark], December 2, 1941, Pearl Harbor Liaison Office, box 29, General Records of the Department of the Navy, RG 80, National Archives at College Park, MD: “You will note that I have issued orders to the Pacific Fleet to depth bomb all submarine contacts in the Oahu operating area.” See also Part 6, p. 2662, of U.S. Congress, Pearl Harbor Attack, Hearings before the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, 79th Cong., 1st sess.

Kimmel’s order is also found among the Kimmel Collection (microfilm) at the University of Wyoming, roll 20: “Additional security mea-sures taken November 27, 1941 and thereafter.”

Stark’s recommendation to employ small surface vessels as lookouts is in Plans, Strategic Studies and Related Correspondence (Series IX), Strategic Plans Division Records, box 147, Part III: OP-12B War Plans and Related Correspondence, WPL-46-WPL-46-PC, Chief of Naval Operations to the Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, February 10, 1941, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, RG 38, National Archives at College Park, MD.