Bakuhatai

The Reconnaissance Mission of the USS Burrfish and the Fate of Three American POWs

Winter 2015, Vol. 47, No. 4

By Nathaniel Patch

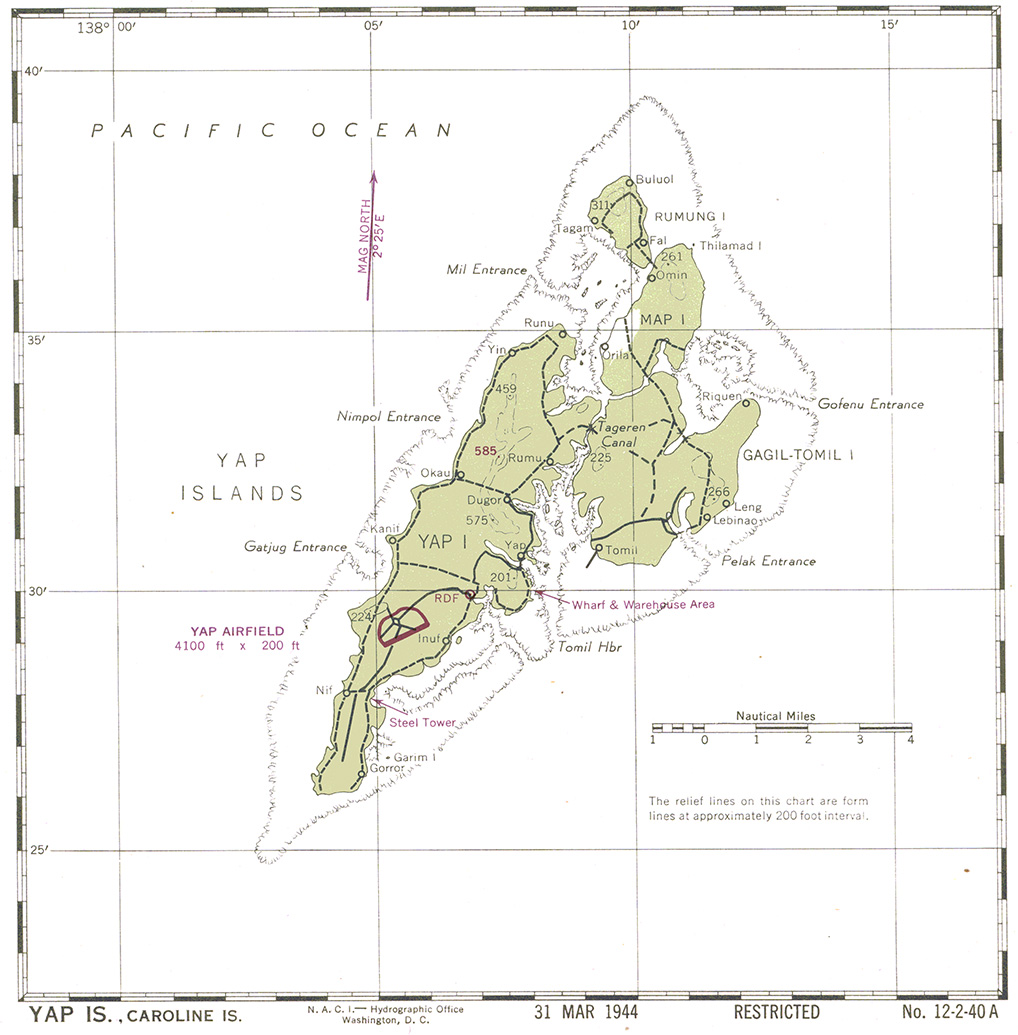

At 8 p.m. on August 18, 1944, the American submarine USS Burrfish (SS 312) surfaced less than two miles northwest off the coast of Gagil Tomil Island in the Yap Islands, one of the Japanese Mandate Islands awarded to Japan after World War I.

Five sailors—wearing swimming trunks, two knives, and black camouflage paint—loaded their swim fins and beach surveying equipment into a small inflatable boat. The five-man unit of the Underwater Demolition Team (UDT), John Ball, Emmet Carpenter, Howard Roeder, John MacMahon, and Robert Black, set out on their reconnaissance mission.

After paddling for an hour through the dark waves, the team reached a reef about 1,100 yards from shore. They measured the depth of coral reef to see if it was deep enough for landing craft. The reef was too shallow, and they debated continuing the mission. Before they could reach a decision, a roller wave tossed the small boat and crew over the reef, sending them toward the beach.

Continuing on, the team anchored the small boat about 500 yards off the beach. John Ball, the boat master, stayed with the boat while the others, in two-man teams, surveyed the beach. Howard Roeder, the crew captain, announced a rendezvous time of 10:45 p.m. and told Ball to leave the beach no later than 11:30. At 9:10 p.m. the teams left the boat. Twenty minutes later, Robert Black returned, hauling Emmet Carpenter, who was exhausted from the rough surf. After helping Carpenter aboard, Black swam back to the beach to continue his mission.

Ball and Carpenter sat in the small boat bobbing in the choppy water, waiting for their teammates’ signal. Thirty minutes past the rendezvous time, they began to paddle up and down the coastline, looking for their companions. At 12:15, Ball decided to return to the submarine rather than risk being left behind if they continued to search.

The crew of the Burrfish was waiting anxiously for any sign of the team, which was an hour and a half overdue. In the dark night against an inky sea, the submarine patrolled around the rendezvous point off the northwest coast of Gagil Tomil, looking for the team. At 3 a.m., the lookout saw a flash of light, and the submarine went to meet the sailors.

When the small boat returned to the submarine, the crew and members of the reconnaissance team were shocked to find only two men. Ball and Carpenter explained that they were late in returning because they were looking for Black, MacMahon, and Roeder, who had not returned from beach surveys.

Commanders Reject Plan to Search Again for Three Men

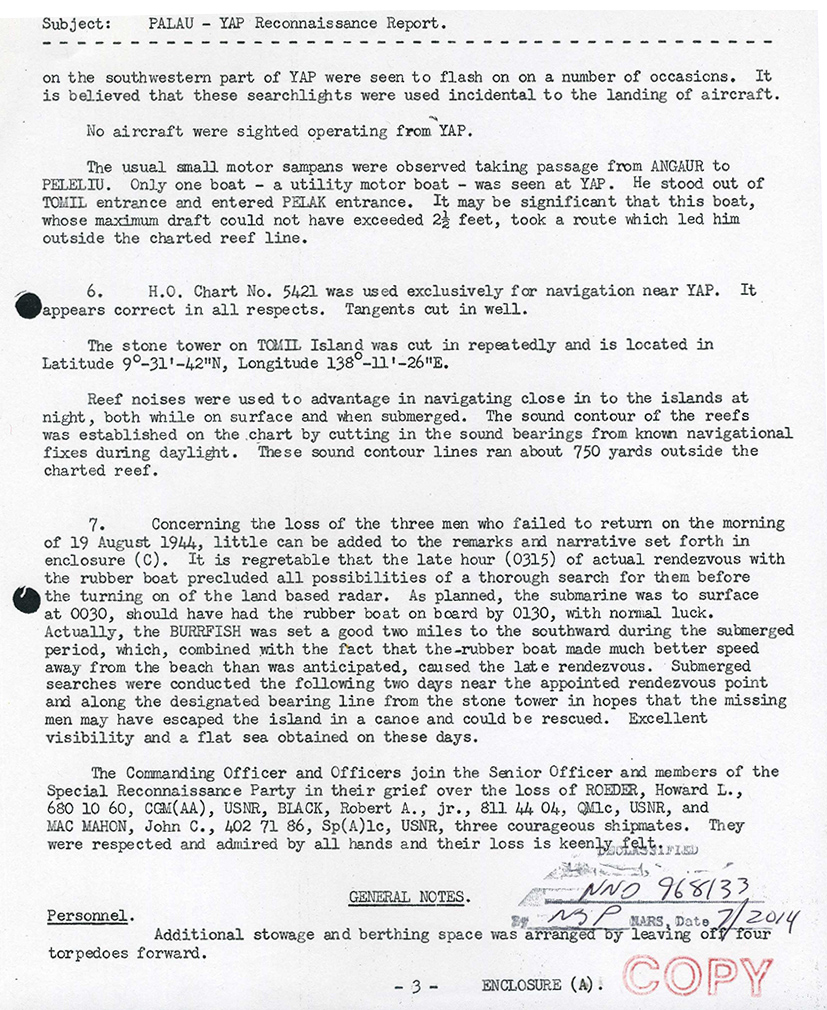

Both the commanding officer of the submarine, Comdr. W. B. Perkins, and the commander of the beach reconnaissance detachment, Lt. C. E. Kirkpatrick, quashed any plan to return to the island that night because it was almost dawn, and the Japanese were about to start a radar scan. Instead, they would send a team to the beach the following night, but for the moment, the submarine had to submerge and observe the island by periscope.

Unfortunately, the following night was stormy, and the waves were too great to launch a small boat without risking more sailors. Regretfully, the Burrfish and remaining members of the UDT detachment sailed to Pearl Harbor, ending the third war patrol of the USS Burrfish and leaving the three swimmers behind on Yap.

With days, perhaps a week, the American military learned through intercepted Japanese radio communications that the Japanese on Yap had captured three UDT frogmen. After being transferred from Yap to the Palau Islands, the Japanese 14th Division sent an intelligence report summarizing what little the captured frogmen had told them. The Japanese referred to their prisoners as “bakuhatai”—Japanese for “demolition”—to distinguish them from submariners. The interrogation report contained basic information about the organization, mission, equipment, and abilities of underwater demolition teams but contained no other information regarding future operations.

The fate of the bakuhatai captured on Yap remains a mystery. They were not liberated from a prisoner-of-war camp, nor have their remains been located. They are still missing in action, and the search for these sailors is still ongoing.

The story of the USS Burrfish and the three missing UDT sailors is part of the larger story of the bloody invasion of Peleliu and the history of naval Special Forces. At the end of the war, Japanese commanders said that all American POWs and other foreign civilian internees were transported to the Philippines when the Palaus finally surrendered in September 1945.

In the postwar occupation of the Palaus and the systematic inquiries of both the Army’s Graves Registration Service and the military’s war crimes section, investigators discovered that many who had supposedly been transferred to the Philippines had actually been killed by their captors in the Palaus. Several groups of POWs who had been captured near the Palau and Yap Islands remain unaccounted for. No evidence of or witness to their executions ever turned up. Howard Roeder, Robert Black, and John MacMahon were likely among those who never left the Palaus.

Underwater Teams Inspect Beaches Before Landings

The Burrfish’s photographic and beach reconnaissance mission was to gather intelligence about the islands of Peleliu, Angaur, and Yap in preparation for forthcoming invasions. Operation Stalemate II was the plan to establish control over the Marianas-Palau-Yap area, with the Palau and Yap Island groups and Ulithi Atoll the chief objectives.

Little was known about the Palau and Yap Islands because they had been part of the Japanese Mandate Islands and thus were off limits to Westerners before the war. There were no tourist photographs of the beaches, maps, or any useful intelligence at hand to help the Navy plan landings. The dense jungle and, in many cases, thick cloud cover obscured the Japanese positions, even after several aerial and submarine photographic reconnaissance missions.

The submarines USS Salmon in April 1944 and USS Seawolf in June 1944 conducted two photograph reconnaissance missions. But the Navy needed more details about the reefs and the beaches. Getting this information meant putting special teams of men close enough to survey potential landing sites.

These Underwater Demolition Teams were organized to survey and inspect beaches before an amphibious landing and to remove natural and man-made obstacles. Members of a UDT, known as “frogmen” or “swimmers,” were usually launched from a fast-transport ship (ADP) and deployed a few days before a landing. For this mission to Yap, however, a submarine, the USS Burrfish, was chosen.

The beach reconnaissance party aboard the Burrfish consisted of members of UDT 10 and personnel from Naval Combat Demolition Training and Experimental Base at Maui, Hawaii. UDT 10 was one of the first at that point in the war to include members of the Maritime Unit of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

The OSS, although known for its intelligence work in Europe, was not as active in the Pacific Theater apart from Indo-China and China. Commanders of the Pacific and Southwest Pacific theaters had developed their own intelligence offices that worked within their chain of command, like the Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Areas (JICPOA).

Adm. Chester Nimitz, however, was interested in one branch of the OSS, the Maritime Unit (MU). Maritime Unit swimmers were similar to UDTs except that they were trained to conduct other intelligence missions besides beach reconnaissance. The MU swimmers used the Lambertson Unit, an early version of scuba gear, and swimming fins. These devices gave them greater endurance underwater, and they were stealthier than the UDTs, who did not use fins but wore sneakers to protect their feet.

Swimmers Headed for Europe Diverted to Pacific by OSS

Through April and May 1944, Nimitz and Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan, head of the OSS, negotiated the transfer of a Maritime Unit to the Pacific theater under Nimitz’s chain of command. Donovan diverted personnel heading for Europe and the Middle East to Hawaii to augment new teams being commissioned. Two of the swimmers aboard the Burrfish, Robert Black and John MacMahon, had been originally assigned to an MU heading for Cairo, Egypt.

The MU swimmers sent to Hawaii became Maritime Unit Group A and were integrated into UDT 10, which had just completed its training. The two units joined at the Naval Combat Demolition and Experimental Base, Maui, Hawaii, on June 19, 1944. Lt. Arthur O. Choate of the OSS Maritime Unit Group A became the commanding officer of UDT 10. From this point, Maritime Unit Group A and UDT 10 trained together as a single unit.

The reconnaissance mission was assigned a few weeks later, in early July, to the submarine and UDT 10. Operational Order 236-44 was classified top secret, which was unusual for submarine war patrols. In this case, secrecy was necessary because the information was to go directly to Commander, Third Amphibious Forces, and could influence last-minute adjustments to the planned invasions of the Palau and Yap Islands.

The operational order was not a typical submarine war patrol order. Its mission priorities were to continue submarine attacks against Japanese shipping, but only if they did not compromise the photographic and beach reconnaissance missions. The order outlined two major tasks: first, to get new periscope photographs of the target beaches in the Palau and Yap Islands, and second, to deploy a special beach reconnaissance party to select beaches on Peleliu, Angaur, and Yap, with extra target beaches set aside on Babelthuap.

The beach reconnaissance party, headed by Lt. Charles Kirkpatrick, was a group of volunteers drawn from UDT 10 and the Maui Training Base. The selection process consisted of several days of vigorous physical training. Eleven officers and enlisted men were finally selected.

The operational order included a cautionary and foreboding warning: “Do not hesitate to break off your reconnaissance before obtaining all information if conditions require. Incomplete information safely brought back is more valuable than complete information that never returned.”

Burrfish Reconnaissance Finds Japanese Radar Stations

On July 11, the Burrfish got under way from Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The forward torpedo room served as guest quarters for the reconnaissance party. The Burrfish took fewer torpedoes than a regular war patrol to accommodate the larger number of people and make empty torpedo sleds available as makeshift beds.

On July 29, the submarine arrived at her patrol area and conducted photographic reconnaissance until August 4. The crew shot pictures of the approaches to Angaur Island and the southern tip of Peleliu. Because they arrived during a full moon, they had to take pictures of the east side of Peleliu from a greater distance.

The Burrfish also took measurements of the currents between Angaur and Peleliu and monitored Japanese shore-based radar. While measuring the currents, the officers observed the beaches through the periscope to orient themselves between the islands. They observed the beach defenses of barbed wire and scullies and saw sandbag pillboxes and other unidentifiable camouflaged positions.

While observing Japanese radar, the Burrfish discovered there were three or more radar stations in the Palaus. They observed no consistent pattern of use, but the Japanese normally turned off their radar at midnight and turned it on again between 3 and 4 in the morning for a pre-dawn scan. The Burrfish also encountered several Japanese aircraft, some of which were using radar to track the submarine. The Yap Islands had one radar station similar to those in the Palaus, with the exception that the radar was shut down at about seven in evening, and then activated between 3:45 a.m. and 4 a.m. for a pre-dawn scan.

After completing the photographic reconnaissance and other tasks, the Burrfish began beach reconnaissance on August 11. The first beach surveyed was the half-moon beach on the southern part of the island (beach 1(b)), which was found to be satisfactory for larger landing craft and amphibious vehicles.

Burrfish Returns to Hawaii; Invasion of Yap Cancelled

Complicating their mission, besides arriving during a full moon, was the activity of Army bombers from Southwest Pacific Area and a naval carrier task force conducting air strikes on the island groups. These strikes put the Japanese on high alert, making it difficult for the submarine to surface and launch the beach reconnaissance teams. As a result, the remaining beach surveys of Peleliu and Angaur (beaches 1(a), 1(c) and 2(a) to 2(b)) were canceled. Comdr. Perkins and Lt. Kirkpatrick determined that it would be safer to press on to the Yap Islands.

On the night of August 16, a team surveyed the southwest beach near Gorror (3(a)) on the southern tip of Yap and found it suitable for all types of landing craft and vehicles.

After Black, MacMahon, and Roeder were captured on the night of August 18, the last survey of beach 3(b), south of the Gofenu Entrance on the east side of the Tomil Gil Island was canceled because a Japanese minefield made the distance from shore too far away for the team to paddle to the reef, and they did not want to risk losing any more frogmen.

The Burrfish, having completed her mission, sailed for Majuro on August 20, arriving on August 27. The mission was considered a success and received a combat patrol insignia. The Burrfish and the beach reconnaissance party eventually returned to Pearl Harbor. Ironically, the remaining members of UDT 10 had boarded the USS Rathburne (APD 25) on August 18, 1944, and sailed to Guadalcanal for advanced training in beach reconnaissance for the landings on Angaur and Peleliu in mid-September.

The capture of the three swimmers caused the planned invasion of Yap to be canceled. Even if the captured frogmen had not told the Japanese about any invasion (which they did not), their very presence suggested that possibility.

Trio of Frogmen Captured, But Give Up Little Information

From the perspective of the U.S. military, the three UDT frogmen—the bakuhatai—disappeared, never to be seen again. Their story continues from postwar interviews with Japanese personnel who served in the Yap and Palau Islands and who had seen them.

The Japanese 49th Independent Mixed Brigade garrisoned the Yap Islands. They spotted an American submarine on the night of August 18–19, and a patrol spotted and captured the three UDT frogmen swimming ashore. It is possible that the three men were captured at different times. One witness said his unit captured Roeder and MacMahon but did not mention Black, who had a later start because he had gone back with Carpenter and was headed to a different part of the beach.

The three Americans were taken to the headquarters of the 328th Battalion, the engineer unit of the 49th Independent Mixed Brigade. They were held there for a few days and were interrogated by Staff Officer Mieno and a first lieutenant from the 323rd Battalion who could speak English. They learned that the frogmen were there to measure the reefs. On August 23 the prisoners were placed aboard the Kise Maru Subchaser No. 27 and sailed to Koror in the Palaus.

When they arrived, the frogmen were taken to a naval guard unit for holding. A short time later they were sent to the main island, Babelthuap, to be interrogated by the South Seas Kempei Tai, Japanese military police, and the intelligence officers of the 14th Division and the Japanese Navy.

Sgt. Maj. Otsuki Yoshie helped escort the three swimmers from Koror to Babelthuap. He took them to Tropical Industries Research Laboratory wharf, where they were met by members of the Kempei Tai. Four or five Japanese navy petty officers guarded the three swimmers, who were blindfolded and loaded into a truck. Kempei Tai soldiers drove the men to their headquarters near Gauspan.

For the next several days, Lt. Col. Miyazaki Artisume, commander of the South Seas Kempei Tai; Lt. Col. Yajima Toshihiko, Army Group Intelligence Staff Officer; Col. Tada Tokuchi, chief of staff for the 14th Division and Army Group; Comdr. Tominaga Kengo IJN; and an interpreter interrogated the three swimmers.

They learned only general information about underwater demolition teams. The Navy’s true objectives in the Western Caroline Islands were known only to Commander Perkins and Lieutenant Kirkpatrick. The Japanese were already aware of demolition teams from the invasions of Marianas, but they were impressed with UDTs and the lengths that Americans would go to gather intelligence.

What happened after interrogation can only be conjectured. Many war crimes were committed in the Palaus, and many missing-in-action cases remained unresolved. In addition to American POWs, captured Indonesians were confined in a prisoner-of-war camp. In addition to the POWs, the Kempei Tai had to deal with civilian crimes as Japanese, Korean, and native islanders stole food and supplies as the approaching Americans cut off the supply lines from Japan.

Differing Accounts Offered About Fate of the Three Men

But what happened to the three UDT frogmen captured in the Yap Islands?

The lack of witnesses or hard evidence regarding their fate means that any answers rely on speculation and inference. Two very different stories arose. One is the Japanese commander’s account that Black, MacMahon, and Roeder were placed aboard a submarine chaser with two other POWs and sent to Manila by way of Davao on September 2, 1944. The other is that the three frogmen and other unaccounted American POWs were executed on Babelthuap following an American air raid on the day that they were supposedly sent to the Philippines.

The first story—sending the POWs to the Philippines—came up immediately after Japanese Lt. Gen. Inoue Sadaei surrendered the remaining Palaus on September 2, 1945. He said all American POWs and other civilian internees had been placed on ships and sent to the Philippines.

In addition to the three UDT frogmen, there were 10 Army Air Force POWs, nine of whom had been taken around the same time as the frogmen (August/September 1944). Civilian internees included two foreign-born families and six Catholic priests who had come from Yap to the Palaus in June 1944. In his 1947 war crimes trial, General Inoue stated that the three frogmen and two Army Air Force aviators boarded the special submarine chaser Uruppu Maru on September 2, 1944.

According to the captain of Uruppu Maru, the ship arrived in Davao, Philippines, on September 10, and the prisoners were transferred to the Zuiyo Maru bound for Manila. The vessel was towing another special subchaser and developed engine trouble and had to turn back several hours later. The prisoners were then transferred to Special Subchaser No. 64, which sailed to Manila; this is where they disappear from the record. The Navy closed the case with no further leads.

Subsequent war crimes investigation revealed that most of these reports of transfers were false. The grim truth was that most of these prisoners had been killed. Witnesses to executions and second-hand accounts of the murders led to physical evidence of mass graves, and the remains indicated the cruel means of their demise. The missing UDT frogmen, however, were not among these remains.

The story of transporting the POWs to the Philippines was obscured by a truth: the Japanese were evacuating Japanese and Korean civilians from the Palaus at this time. Port personnel in Davao attested to remembering immigrants and refugees, but not POWs, arriving during the first week of September.

Testimony from another Japanese officer indicated the obfuscation in the shipping cover story. When the interviewer asked him who had come up with the story about sending “prisoners” on ships to the Philippines, he stated that Lt. Colonel Yajima of Army Intelligence and Colonel Tada, the 14th Division’s Chief of Staff told him to use that excuse. Yajima stated that Tada had instructed him to prepare reports giving false testimony regarding American POWs being sent to Davao.

During the early part of the American occupation of Palau, however, the American Graves Registration Service, with assistance from natives and some Japanese, uncovered mass graves of people who had supposedly been transferred to the Philippines, including the priests, two families, and several Army aviators. This discovery raised the possibility that the UDT frogmen had also been executed on Babelthuap and not been sent to the Philippines.

Were the Three Men Executed after Capture?

The most direct statement regarding the murder of the prisoners came from Yajima’s affidavit of June 27, 1947, where he states that after interrogation, the swimmers were returned to the Japanese Navy’s custody, and they were “killed by the Navy.” Another soldier corroborated, saying he had heard the prisoners were drowned or killed in the water at the hands of the Japanese Navy.

Another admission of guilt can be inferred from comparing two descriptions of one conversation that took place on September 2, 1944, among Miyazaki, Yajima, and Tada to discuss General Inoue’s plan for disposal of the POWs.

An air raid interrupted Yajima’s interrogation of three U.S. Army aviators, and both Japanese personnel and prisoners were taken to the air-raid shelter. While waiting out the bombers, Tada told Yajima to cease the interrogation of the aviators and informed Miyazaki and Yajima of Inoue’s intention to dispose of the prisoners. Inoue wanted Miyazaki to take care of it. Miyazaki stated that he would.

In the first interpretation of this conversation, from an investigation report dated September 25, 1947, Tada makes a general remark of there being prisoners, but he does not say which ones. The second interpretation came from Inoue’s trial, when the prosecution referenced the same conversation. In this interpretation, “prisoners” refers only to the three aviators because they were the only ones for whom prosecutors had material evidence of their September 4, 1944, executions.

Between August 19 and September 4, 1944, there were as many as 12 American prisoners of war in the Palaus: 3 were the UDT swimmers, and 9 were Army Air Force aviators from four crashed bombers. The actual number of prisoners of war in the Palaus is unknown, but clearly there were more than three. Several participants in and witnesses to the Japanese interrogations testified to larger numbers.

Other Japanese personnel kept confusing groups in their testimonies. So when Tada remarks that there are “prisoners” to dispose of, which prisoners were he referring to? Tada said that Inoue had orders from Lt. Gen. Hideyoshi Obata, commander of the 31st Army, stating that in the event of an American invasion, he was to dispose of all POWs. The increased U.S. bombing campaign in preparation for the invasions of Peleliu and Anguar heightened Japanese expectations and further convinced them of the American advance.

Miyazaki’s taking responsibility was odd because Inoue had no authority over him. The Kempei Tai was under the command of the South Seas Civil Government and not the Palau Army Group. Neither the Army nor the Navy had administrative control over the Kempei Tai. Regardless, if Miyazaki felt that this was an order, he agreed to it, and the most logical result was that the three aviators, along with the three UDT frogmen and six other aviators who had been supposedly shipped to the Philippines, were executed on September 4, 1944.

Search for Fate of the Three Continues Seven Decades Later

The third war patrol of the USS Burrfish in the the Yap and Palau Islands was considered a relative success. If nothing else, it demonstrated that a small band of highly trained frogmen could be deployed from a submarine to conduct an operation on an enemy-held island.

However, three UDT frogmen were taken prisoner and, because of bad planning, more than half the beaches selected to be surveyed were bypassed. The mission resulted in the cancellation of the landings in Yap and did not yield any new intelligence for the landings in Palaus.

Lieutenant Choate, the commanding officer of UDT 10, remarked in his evaluation that they had only just completed training when this mission was announced. The two parts of the team, the UDT frogmen and the MU swimmers, had very little time to get back into shape from weeks of traveling to Hawaii and less time to train together for the new mission.

Repairs made to the Burrfish before the mission—to remove and reinstall noisy propeller shafts—were both a blessing and curse. These repairs gave the UDT volunteers a little more time to train, but it also delayed the mission, causing it to be conducted under a full moon instead of a new moon as originally planned.

The last encumbrance to the mission was the air raids on the Yap and Palau Islands while the reconnaissance mission was under way. These attacks were counterproductive, causing the Japanese to increase radar searches and aircraft patrols, which jeopardized the Burrfish and the beach reconnaissance party while surveying Peleliu and Angaur.

As for the fate of Robert Black, John MacMahon, and Howard Roeder, it seems evident that they and the other unaccounted Army aviators were executed on Babelthuap, probably around September 4, 1944, when the three known Army aviators were executed. Both Yajima’s statement that they were “killed by the Navy” and the conversation in the air-raid shelter, where it was stated that all prisoners were to be disposed of in light of the American advance into the Palaus, support this conclusion.

The policy of terminating prisoners in advance of an American invasion can be seen in the Palawan massacre later that year. This horrific policy motivated the U.S. Army to use raids to liberate other Japanese POW camps in the Philippines prior to the American advance.

Culpability for the executions has been obscured. General Inoue and Colonel Tada were convicted of war crimes in Guam in 1947. Colonel Miyazaki, whom others identified as responsible for several executions of POWs, escaped trial when he committed suicide before being taken to Sugamo Prison.

To the evident relief of those trying to avert responsibility for their own crimes, the testimony of his colleagues and subordinates placed the blame on him.

To this day, the Defense Prisoner of War and Missing in Action Accounting Agency (DPAA) and the volunteer group, the BentProp Project, continue to investigate the missing UDT frogmen and other cases in the Palaus. They search for evidence that the UDT swimmers were transported and lost among the thousands of unknowns in the Philippines or executed in secret on the island of Babelthuap. They search the records at the National Archives and other agencies for any information that might locate missing serviceman.

With continued research, perhaps the frogmen’s secret burial place will be found, and they can be returned and be no longer among the missing.

Nathaniel Patch is an archivist in the Reference Branch at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, where he is on the Navy and Marine Corps Reference Team. He has a B.A. in history and an M.A. degree in naval history with an emphasis on submarine warfare.

Note on Sources

I had originally wanted to describe a submarine photo-reconnaissance mission with the intent of continuing a series of articles on missions of American submarines during World War II. The mission of the Burrfish was unique because, unlike other photo-reconnaissance missions, where the submarine takes pictures of the shoreline from the periscope, this mission included a detachment from Underwater Demolition Team 10. The story became more intriguing when I learned that three men from this detachment had been captured, taken prisoner, and then disappeared into the fog of war.

Daniel O’Brien of the BentProp Project, after overhearing me tell my story to a colleague, told me his group would be interested in my research because these men were still missing. He explained that there were some odd dimensions to this story, including OSS involvement, rescue missions, and the UDT POWs being placed aboard ships heading off to the Philippines, never to be heard from again. Although I was intrigued, I was overwhelmed and didn’t know where to start. I asked Christine Cohn of the Defense Prisoner of War and Missing in Action Accounting Agency (DPAA) for her advice, and she became interested in anything that I could contribute. I gave myself a year to see what I could find out.

In researching this story, I initially started with Third War Patrol Report of the Burrfish, the action reports of the Burrfish and UDT 10, and the operational order 263-44 in Record Group 38, Records of the Chief of Naval Operations. I also used the deck log of the Burrfish for the period of her third war patrol. From these records came the basic story of what the mission was and how the UDT members had disappeared.

The research took me into new and unfamiliar records, including war crimes trial records in Record Group 125, Records of the Judge Advocate General (Navy); intercepted enemy radio traffic in Record Group 38, and intelligence bulletins in COMSUBPAC administrative files in Record Group 313, Records of Naval Operating Forces. I also used a number of non-Navy record groups, including OSS records in Record Group 226, to learn about the Maritime Unit in Honolulu and the relationship between the OSS and Nimitz; the Philippine Archives in Record Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, for prisoner of war records; Graves Registration units in the Palaus in Record Group 92, Records of the Quartermaster General’s Office; and War Crimes Trials records in Record Group 153, Records of the Judge Advocate General (Army).

This was a great learning experience. I would like to thank Christine Cohn, Corbin Colbourn, and Edward Burton of DPAA for their assistance and giving me access to pertinent records held by their office relating to this topic and their advice. I would also like to thank Daniel O’Brien, Mark Swank, and Patrick Scannon of the BentProp Project for access to their files and their advice on this topic.

I hope this will be helpful in locating these men and give closure to their families.