The Men—and the Women—Who Built the Washington Monument

Spring 2016, Vol. 48, No. 1

By John Lockwood

Immediately after George Washington—hero of the Revolution, Father of His Country—died on December 14, 1799, Congress declared a period of national mourning and proposed a memorial to the first President.

Over the subsequent years, the government endorsed several efforts to build a monument to Washington in the national capital named for him. Nothing came of them, however, until a group of private citizens took matters into its own hands in 1833.

The Washington National Monument Society held its first meeting on September 26, 1833, at the old City Hall, to choose its officers and make plans. Chief Justice John Marshall was elected the society’s first president. Succeeding meetings drew up a constitution and plans for fund-raising.

To raise money for a monument, the society decided to designate collection agents in each town or county across the country to go door-to-door asking for donations. At first, the society hoped the agents would be unpaid volunteers, but it eventually had to settle for allowing a 10-percent commission on money collected, later raised to 15 percent.

The society made three mistakes at the outset. First, it limited each donation to only one dollar, even if the donor wanted to give more. It was felt that such a limitation was more democratic because poor donors would not feel shamed by the sight of rich donors contributing far more. If money came pouring in, as they confidently expected, a ceiling of a dollar apiece would not matter.

The second mistake, written into the society’s constitution, was to limit the donations to the “white inhabitants” of a given area, though it is possible that some agents in the field may have ignored this.

The third mistake was to not allow women members or agents, which reduced potential donations even further.

Funds Weren’t Forthcoming According to the Group’s Plan

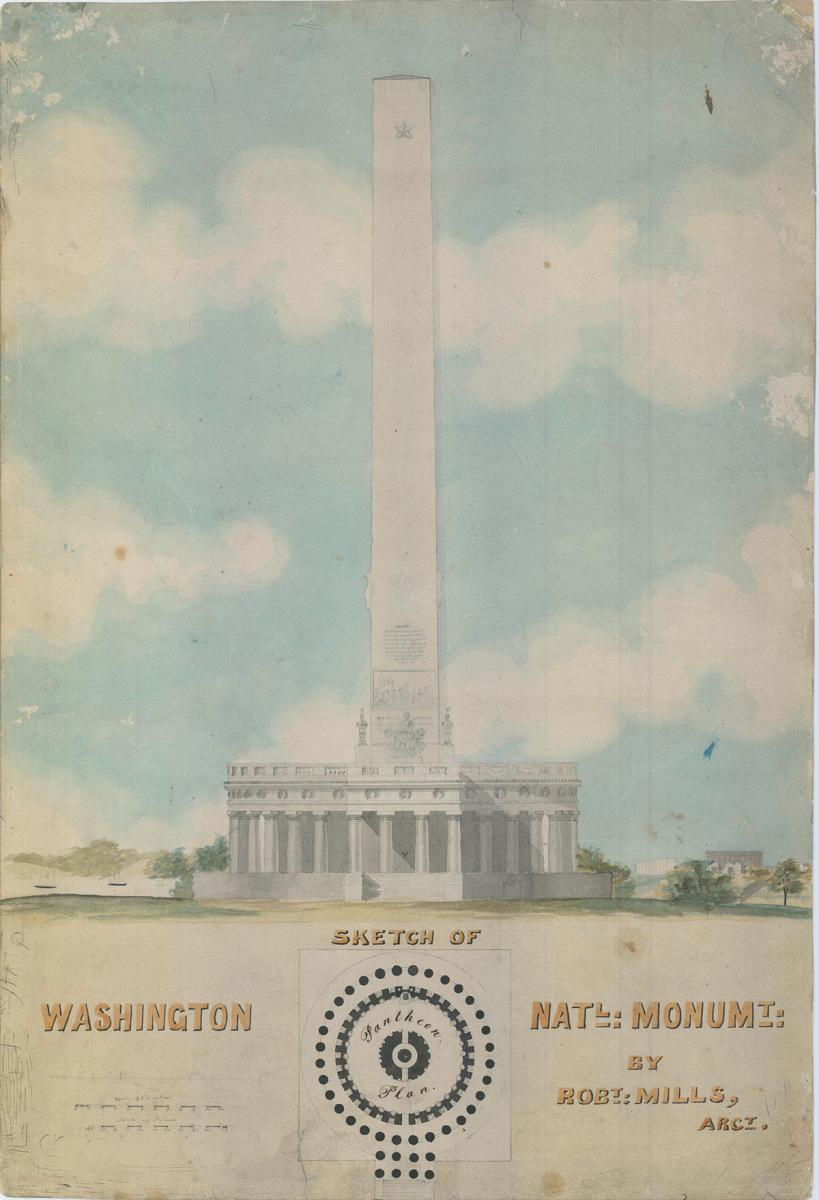

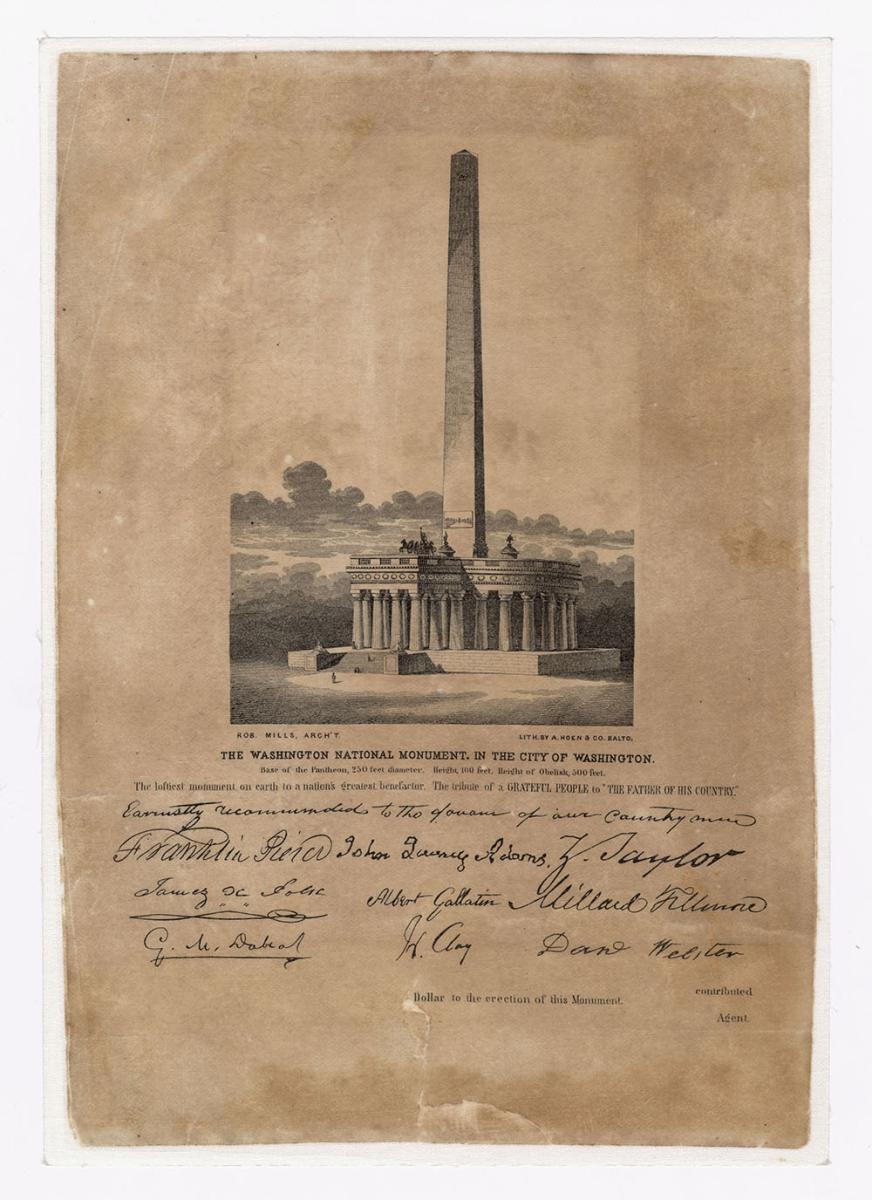

The society held a nationwide competition in 1836 for the design of the monument. The winner was one Robert Mills, already well known for designing the Washington Monument in Baltimore and the U.S. Treasury building adjacent to the White House. His design consisted of an obelisk 600 feet tall, with a Greek colonnade or circle of pillars surrounding it, 150 feet high. The column’s top was almost flat, with a barely discernible point. There was to be access for visitors, with a steam engine pulling passenger carts to the top.

From the first, the society had trouble collecting money. By 1838, it had only $28,000 for a project whose estimated cost was about $1,000,000 (about $28 million in today’s dollars). The society kept trying, though, and eventually removed the dollar- per-donation limit. The records do not show whether it ever removed the color bar.

In the 1840s the society invested the money in stocks, bonds, and banks. By 1848, it had $87,000 on hand—enough, it was felt, to start work and hope for the best. In addition, Congress had just donated a stretch of land south of the White House as the site for the new monument.

The ground itself was a low hill with pine trees on it, and only a few hundred feet away from the Potomac River. Today’s shoreline, where the river is almost a mile away, is the result of land reclamation projects in the late 19th century. In 1848 the closeness of the river allowed barges to deliver stone blocks almost to the building site, after which sledges drawn by oxen could drag the stone the rest of the way.

Work officially began on April 18, 1848, when the first shovelful of earth was dug up. There was a small ceremony for the occasion. In the next few months, workmen would remove the little hill and dig a hole for the foundation.

The really big ceremony was planned for laying the cornerstone, on July 4, 1848, the 72nd anniversary of American independence. President James K. Polk presided. A good many members of Congress were present too, including a young man named Abraham Lincoln, then serving his first and only term as a Representative from Illinois. Military companies attended, as well as Masons and other societies. Parades during the day were followed by fireworks at night.

Perhaps the most poignant part of the ceremonies was the presence of two elderly women from the Framers’ generation—Dolley Madison, widow of President James Madison, and Elizabeth Hamilton, widow of Alexander Hamilton.

With the Cornerstone in Place, Plaques Began Arriving

The cornerstone itself contained a zinc case serving as a time capsule, stuffed full of books, speeches, a medal, and 71 newspapers from across the country. Several relic-hunters broke off a few chips of the cornerstone as souvenirs. Representatives of the Masons conducted a brief ceremony, placing on the cornerstone oil, wine, and corn, symbolic of peace and prosperity. After all, Washington himself had been a Mason.

After this promising start, construction con-tinued for several more years. On April 20, 1849, the foundation was finished, and the shaft itself had already passed the 10-foot level. By December 20, 1849, when work stopped for the winter, the shaft had reached over 50 feet, and a just-installed 70-horsepower steam engine was being used to hoist the stones to the top.

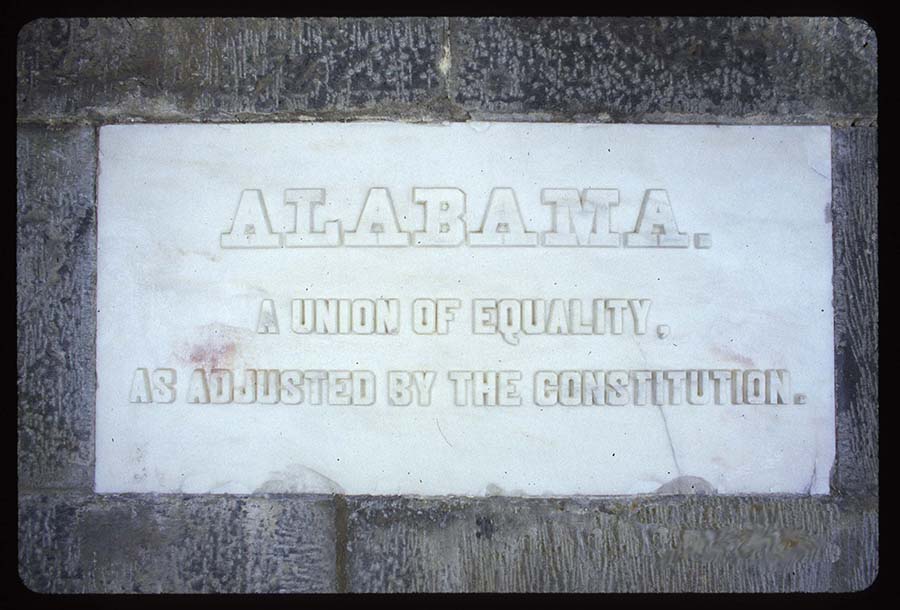

Also in 1849, the state government of Alabama donated a plaque in honor of George Washington, to be installed on the inside wall. The idea instantly caught on, and soon dozens of plaques were coming in from other states, cities, and organizations such as the Masons, businesses, and many foreign countries.

Many were accepted; others were rejected because of poor workmanship or because they were really advertising themselves rather than revering Washington. The Masons proved the most generous contributors. Some 21 of their stones still grace the monument today, more than any other group or profession.

Even now, the society still had trouble collecting money. It tried various other ideas of fund-raising, in addition to using collection agents. The society put collection boxes across the country—at government offices, hotels, fairs, churches, election sites, and the monument itself. It offered souvenirs, such as certificates signed by the President and other VIPs.

And, to save money, the society dropped the idea of a colonnade around the base of the obelisk.

The society had to reduce expenses whenever it could, almost to the point of cornercutting. One obvious example of this was the composition of the walls of the monument: they were not actually solid. The outer layer was made of marble and the inner layer of gneiss—but in-between, the builders filled the space with irregular gneiss rubble.

The 1934 Restoration Provides More Strength

In 1934, during the first restoration of the monument, this section was strengthened by having liquid cement poured in at the 150-foot level, letting gravity fill up the gaps down to ground level. The round holes, now plugged, may still be seen at that landing, where the cement was added.

As a further cost-cutting measure, the inner layer of gneiss was cut by hand, even though (more expensive) machine cutters were available. A glance at the old inner walls today will show that every available piece or broken segment was used—as opposed to the machine-cut rectangular blocks further up, which were cut to precision.

The marble the society used for the outer layer must have come from one of the lowest bidders. It proved to be what would later be called “alum marble” because it crumbled so easily.

Today, for example, the corners of the monument have long since been replaced by new, whiter marble up the first 10 feet or so, the old material being damaged by erosion–and more relic-hunters. There are also scattered replacements further up to 150 feet, after which no replacements were needed.

During the 2000 restoration, there were piles of old society marble taken down and stored behind the scenes. One could pick up a lump and crumble it like cheese.

Women’s Groups Step In and Help Keep Project Going

The Washington National Monument Society did the best it could on a shoestring budget. Despite later repairs, the basic structure was sound—indeed, it is still there today. In mid-December 1854, however, the society had to announce that work would cease. It had spent $230,000 and raised the column to 152 feet. In 1855, Congress debated appropriating $200,000 for the monument to get things started again, but in that year the society was taken over by the American Party, better known as the Know-Nothings. (When asked about their activities, they would reply, “I know nothing.”) The party was a brief successful nativist movement in the mid-1850s that did not like Catholics and thought that the Pope wanted to control America. Ironically, they sometimes called themselves Native Americans.

After Pope Pius IX donated a commemorative stone to the Washington Monument, the Know-Nothings bought up memberships for themselves in the society, at one dollar apiece. They then showed up for the next meeting and overwhelmingly voted in their own people as officers. The original society refused to recognize the results, and so for a time there were two societies meeting side-by-side in the same small room in the City Hall’s basement.

After this, almost no one wanted to contribute anything. The Know-Nothings ended up using rejected marble lying about the grounds and so added a total of three feet, three inches to the monument. The original society regained control in 1858.

In 1859, a little-known episode in the monument’s history showed that the nation’s women refused to sit on the sidelines.

Several women founded the Ladies Washington National Monument Society. The Ladies group was created in Chicago, sometime in September, appropriately enough at the Masonic National Convention. A Mrs. Finlay M. King of New York was elected the president, and Mrs. Anna M. Cosby of Washington, D.C., became the secretary.

All the officers, in fact, were women. Perhaps they were inspired by the newly formed Mount Vernon Ladies Association, which in 1859 bought the old George Washington estate, restored it, and still run it today.

The new association published an “appeal to the people,” beginning: “The Monument of GEORGE WASHINGTON remains unfinished in the capital of the Republic he founded. Do you revere his name and memory?” It added, “Shall we prove recreant to the obligations this imposed on us? We cannot believe such a thing possible.”

Collection efforts in Washington, D.C., began on George Washington’s birthday, February 22, 1860. The first reports of the results appeared in the local Daily National Intelligencer of March 5, 1860, on page 1, and it was apparent that the Ladies group was already in trouble: “From the Masons of this city, through Major B[enjamin] French, $9.41; Kirkwood’s Hotel, $6.81; Washington House, 67 cents; Willard’s Hotel, 66 cents; Clarendon House, 34 cents; National Hotel, 55 cents; Brown’s Hotel, 12 cents; United States, 55 cents. Total $18.80.”

The Ladies society was, in short, having as much trouble prying open American wallets as their male colleagues. The next notice was in the Intelligencer for December 4, 1860, page 1, and listed local collections from the presidential election, the one that elected Abraham Lincoln. The total collection in the Washington area was $154.46.

Nationwide collections were little better. For 1861, the national total was $298.33. The Civil War had begun by now, and people had other things to think about than the monument. Sometime in 1863, the Ladies Washington National Monument Society disbanded.

Army Engineers Take Over as Construction Resumes

There things sat for the next several years. Finally, on August 2, 1876, Congress passed a law to resume construction. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was to complete the job, led by Lt. Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey. Casey already had experience in building things. During the Civil War, he had put up a string of forts in Maine, in case disputes with the British should lead to a military threat from Canada. Later, in the 1890s, he was in charge of the construction of the Library of Congress, which stands just behind the Capitol.

Before doing anything else, Casey had to strengthen the monument’s foundation, which had proven to be quite inadequate for the weight to be placed upon it. Part of the original gneiss material was removed and replaced with concrete. The whole was then reinforced further by more concrete, completely encasing the foundation in a massive apron shape. For a brief time, the cornerstone was visible again, before being covered over for good. And a few more gentlemen who should have known better broke off chips as souvenirs.

As for the shaft, Casey removed the inferior Know-Nothing stone, plus two more feet of Washington National Monument Society stone, which was weather-damaged. Casey could then start fresh at the 150-foot landing.

On August 7, 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes was on hand to dedicate a second cornerstone at the 150-foot level. This one had no time capsule. Despite occasional trouble with supplies, the monument now grew steadily over the next few years.

At the behest of George P. Marsh, a scholar and diplomat of the day, the planned height of the column was reduced from the original 600 feet. In a true Egyptian obelisk, the height is 10 times the width at the base. The base was 55 feet, 1½ inches wide, and the column’s eventual height under the new plan ended up at 555 feet, 51/8 inches. Also, the pyramidion, the pointed peak forming the last 10 percent of the monument, was made much steeper than in the original plan. Its height was now greater than its width, again as in a true obelisk.

On December 6, 1884, the Washington Monument was finished at last.

As a crowd watched from below, Casey and several other staff met at the top, aboard a wooden platform made up for the occasion. Casey himself put in place the eight-inch aluminum tip. At the time, aluminum was a rare and expensive metal because the technology of the day found it dif- ficult to extract the metal from its ore.

On February 21, 1885, another crowd attended the monument’s formal dedication. It would have been February 22, George Washington’s birthday, but because that day was a Sunday, the dedication was moved back one day.

And so the Washington Monument became one of the city’s premier symbols.

John Lockwood is a native Washingtonian who has published some 169 articles in newspapers and magazines since 2002. He and his late brother Charles also wrote a book for Oxford University press, The Siege of Washington, about the nearly defenseless condition of Washington, D.C., during the first 12 days of the American Civil War.

Note on Sources

The microfilmed newspapers at the U.S. Library of Congress proved quite useful for this article, providing much information on the monument’s history, especially that written during and just after it’s completion.

The best single source, however, is the treasure trove of data within the Records of the Washington National Monument Society in the Records of the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, Record Group 42, at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C.