The Zimmermann Telegram

And Other Events Leading to America’s Entry into World War I

Winter 2016, Vol. 48, no. 4

By Jay Bellamy

“No account of the stirring episodes leading up to our entry into the World War can be considered complete without at least a reference to the one in which the Zimmermann telegram played the leading role.”

—1938 study by the War Department Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

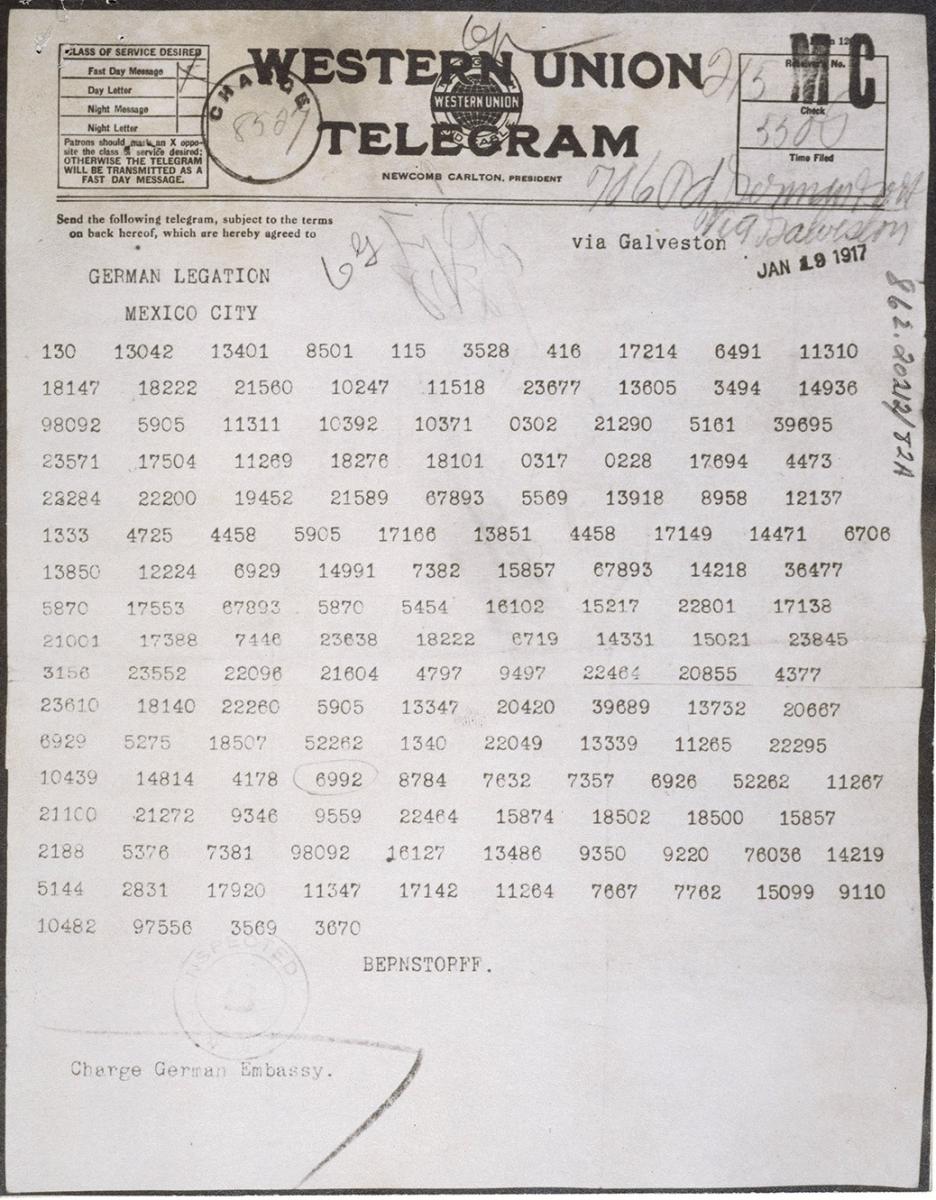

At first glance, the telegram dated January 16, 1917, appeared to be nothing more than a series of numbers running across a page.

To the casual observer, these three- to five-digit number sequences (130, 13042, 13401, 8501) would seem nonsensical.

But the British cryptographers, whose duty it was to root out secret codes, knew better. They formed the nucleus of the British Admiralty’s code-breaking organization known as Room 40. Using captured German codebooks found in combat and through military intelligence, the British concluded that the coded message they were reading had been sent by the foreign secretary of the German empire, Arthur Zimmermann, to the German ambassador in Washington, Johann von Bernstorff.

The Room 40 codebreakers intercepted the message as it briefly passed over British territory. The Germans were often forced to use cables belonging to neutral countries after their own Atlantic cables were cut earlier in the war.

Once the Zimmermann telegram was decoded, the British knew they were on to something big—but the question facing them was what should they do with it?

An Assassination in Sarajevo Plunges Europe into War

World War I had begun nearly three years earlier when Archduke Franz Ferdinand—the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne—and his wife, Sophie, were assassinated on June 28, 1914, while making a goodwill visit to Sarajevo, Bosnia.

Because anti-government feelings ran strong in this territory, which had been annexed by Austria-Hungary, the archduke was warned against going. Franz Ferdinand, however, insisted on making the trip, arguing that this would also give him the opportunity to inspect military maneuvers taking place just outside of Sarajevo.

The assassination was carried out by 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip, who was acting on behalf of the Black Hand Society, a nationalistic group advocating the liberation of all Serbs under Austro-Hungarian rule.

Believing that Serbia itself was behind the archduke’s murder, Austria-Hungary issued a set of demands so severe that Austro-Hungarian leaders were convinced the Serbs would refuse to honor them, thus giving them a reason to declare war on Serbia.

To everyone’s surprise, Serbia accepted the bulk of the demands but drew the line when it came to allowing Austria-Hungary to conduct its own investigation into the archduke’s murder. With Germany’s encouragement, Austria-Hungary then declared war on Serbia. Soon the world powers, through various treaties of their own, began aligning themselves on either side.

From the war’s outset, however, President Woodrow Wilson was determined to keep the United States out of the war and to remain neutral. This, however, became increasingly difficult to do, as more and more citizens and political leaders called on America to enter the war on the side of the allies.

Germany Sends Spies, Saboteurs; British Seek U.S. Entry into War

Despite U.S. claims of neutrality, the Germans were very much aware that American munitions depots were supplying ammunition to the British, and several German spies and saboteurs—many of them U.S. citizens who still maintained their allegiance to Germany—were known to be in the states to try to halt shipments from leaving the country.

Although his official title was German ambassador to the United States, Bernstorff was told before departing for America that he was to serve as Germany’s espionage and sabotage chief for the Western Hemisphere. Even as he was constantly assuring President Wilson that his country wished for a quick resolution to the war, he was ordering attacks on American supply depots.

Wilson, meanwhile, continued to hold firm to his neutrality policy and even allowed Bernstorff to use American transatlantic cables to send diplomatic messages back and forth between Germany and the West. At the same time, Bernstorff had been paying off several American reporters not only to write favorable articles about Germany but also to serve as couriers.

Acting on a coded message intercepted by the men of Room 40, on September 1, 1915, British soldiers boarded a ship near Falmouth, England, and apprehended American journalist James Archibald. Inside his briefcase they found, among other things, sabotage progress reports written by German military attaché Franz von Papen and Karl Boy-Ed, the German naval attaché to the United States.

Hoping to draw America into the war, Britain leaked the letters to the American press. These letters, coming on the heels of the German torpedoing of the luxury liner Lusitania on May 7, convinced the British more than ever that America needed to take a stand in the war. Of the 1,959 passengers on board the Lusitania, 1,198 were killed, and 128 of them were Americans.

Pressure Grows for War; Trouble Brews with Mexico

Up to this point, Wilson had rejected several State Department requests to investigate von Papen, but in November, Secretary of State Robert Lansing wrote to the President suggesting that von Papen and Boy-Ed be expelled from the United States. Wilson finally agreed.

On December 10, after receiving a letter from Lansing demanding that both von Papen and Boy-Ed be recalled, Bernstorff officially recalled the two men to Germany.

Von Papen vigorously proclaimed his innocence, but when members of the British navy checked his luggage upon his arrival in Falmouth, England, they found a checkbook showing deposits of more than $3 million, as well as more than 100 check stubs written to suspected German saboteurs.

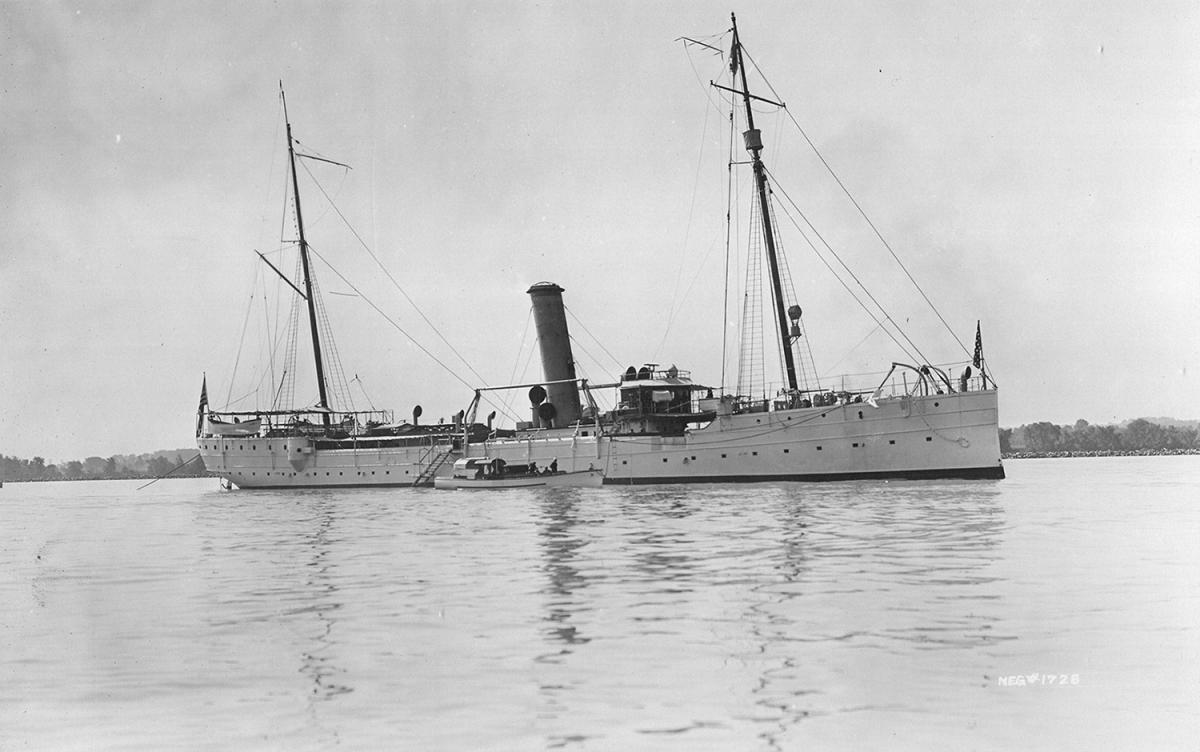

On April 9, 1914, three months before the start of World War I, the crew of the USS Dolphin was detained while purchasing fuel in Tampico, Mexico. Unbeknownst to the sailors, this particular fueling station was located in a spot that had previously been declared off limits to foreigners. Although the American sailors were quickly released, their commander, Adm. Henry T. Mayo, was enraged.

In a dispatch to Gen. Ignacio Zaragoza—the commander of Federal forces at Tampico—Mayo demanded that a 21-gun salute be given as an official apology and that the American flag be raised and saluted. Gen. Victoriano Huerta, the president of Mexico, claimed to be fearful of anti-American acts if he gave in to U.S. demands and refused to honor “the humiliating terms of the United States.”

On April 20, Wilson addressed Congress and asked for approval to use military force if called for, declaring that any action taken was simply to “maintain the dignity and authority of the United States.”

The Tampico affair was hardly an isolated incident, he told Congress, and it was important that Huerta show remorse for “slights and affronts” committed against the United States for its refusal to recognize him as Mexico’s Constitutional Provisional President.

U.S. Intercepts German Ships, Seizes Port of Veracruz

When Wilson received word on April 21 that a German ship was headed toward Mexico with weapons for Huerta, he ordered American troops to seize the customs office at Veracruz to prevent the arms from reaching him. Once the U.S. Navy intercepted the German ship, thus enforcing the arms embargo Wilson had placed on Mexico, American soldiers stormed Veracruz, intent on taking possession of the customs house and railroad yards, as well as the cable, telegraph, and post offices.

Several U.S. battleships and cruisers arrived later that night, carrying additional troops to reinforce American forces already deployed in and around Veracruz.

The Americans advanced on the Mexican naval academy the following morning, and by the end of the day, American forces, with the help of warships in the harbor, were in control of Veracruz and would remain there for the next seven months.

In July, bowing to pressure from Mexican revolutionaries, Huerta resigned his position and went into exile. Venustiano Carranza replaced him.

On January 10, 1916, a group of outlaws associated with the legendary Mexican bandit Pancho Villa stopped a train near Santa Isabel, where they lined up 17 American mining engineers and shot them down in cold blood. Some historians believe this attack was in response to the American government’s support of Carranza, and not Villa, as Mexico’s official leader.

Just two months later, Villa and his men crossed the Mexican border into Columbus, New Mexico, in search of supplies. As they rode through town, ransacking stores and burning down houses, they were confronted by troops attached to the 13th Calvary stationed at Camp Furlong.

The 13th was able to repulse Villa’s attack, but not before 18 American civilians and soldiers were killed. In return, Villa lost nearly 100 of his own men before the remaining marauders escaped back over the border into Mexico.

Carranza agreed to allow American forces to enter Mexico for the sole purpose of capturing Villa. On March 16, Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing crossed the border with an expeditionary force determined to bring Villa to justice.

However, Wilson had stipulated that Pershing’s men respect the sovereignty of Mexico and avoid any kind of altercation with the Mexican army. This proved difficult to do. The Mexican military resented the American presence in Mexico and even fought against them in Carrizal on June 21, when American forces were tipped off that Villa might be found there.

By January 1917, with Pancho Villa still on the loose and diplomatic relations between the United States and Mexico further strained, the Mexican expedition was called off.

Fire, Explosions Destroy Arms Bound for Britain

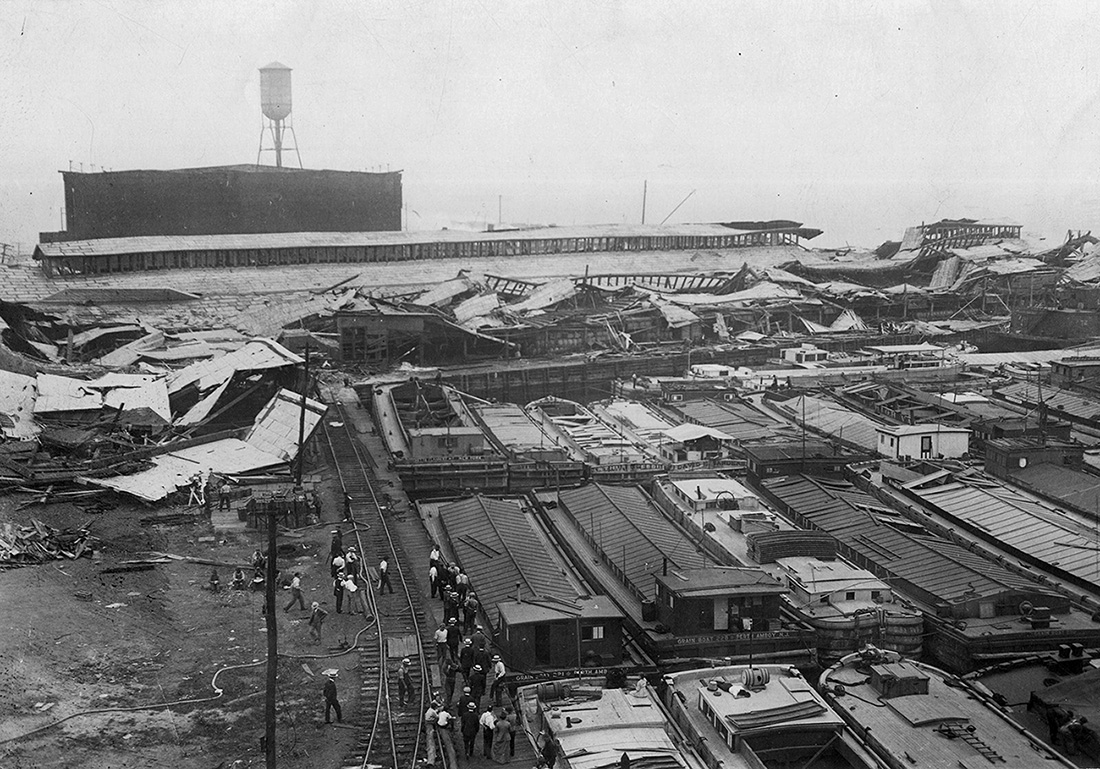

By 1916, America had become the largest supplier of arms to Britain, much of it coming from Black Tom in New Jersey, a strip of land located on the western shore of the upper bay in the New York harbor. Formerly an island, the space between the island and shore—as well as parts of the island itself—had been filled in to provide easier access.

Black Tom was made up of numerous warehouses, piers, train tracks, and loading docks that had been extremely busy since the start of the war. It was a prime target for saboteurs.

At approximately 12:30 on the morning of July 30, 1916, a security officer spotted a fire coming from the train yard. Once the fire spread to the tracks, railroad cars holding explosives began detonating.

According to a Bureau of Explosives report, the cars contained a total of 550,000 pounds of dry trinitrotoluol, 965,000 pounds of wet trinitrotoluol, 25,200 pounds of trinitrotoluol in shells and cartridges, 6,415 pounds of black powder, and 53,437 pounds of smokeless powder.

It was nearly 1:30 a.m. when the Jersey City fire department arrived and found the fire burning too hot for them to get near the exploding cars. As tugboats began pulling barges away from the piers, one of the barges exploded. On board was more than 100,000 pounds of TNT. The sound and vibration was heard and felt as far away as Jersey City and caused severe structural damage to many buildings throughout the city and overturned tombstones in local cemeteries.

Black Tom Explosions Rock New York City Skyscrapers

Just over 30 minutes later, a second explosion rocked Black Tom. The shock from this blast shook the Brooklyn Bridge and broke windows in several New York City skyscrapers. People standing on the Jersey City docks, a mile to the north, were thrown to the ground by the sheer force of the blast. Across the harbor, shrapnel tore into the chest of the Statue of Liberty, and rivets holding the torch to the arm were popped. The arm of Lady Liberty has been closed to tourists ever since. Surprisingly, the Black Tom explosion resulted in only five deaths.

Although many believed German saboteurs were responsible, it wasn’t until 1939 that Germany was held accountable for the explosion and ordered to pay $50 million in restitution. It is believed that Franz von Papen—the attaché expelled from the United States the previous year—was most likely responsible for the initial planning.

Throughout the war, German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann had been opposed to unrestricted submarine warfare. He was concerned that this might lead Wilson to abandon neutrality and allow America to enter the conflict on the side of the allies. By December 1916, however, he had changed his position and now supported the idea.

In contrast, Bernstorff, who wasn’t above a little sabotage here and there, believed unrestricted submarine warfare was an open invitation for America to go to war and was attempting to halt the use of U-boats before they could be put into service.

On December 28 he met with Edward House—one of Wilson’s closest advisers—to discuss a plan the President had proposed.

Believing that Germany was interested in finding a peaceful solution to the war and knowing they were unwilling to make any terms of peace known publically, Wilson suggested that any proposals be transmitted over the State Department cable. In return, Bernstorff promised that his government would send only peace terms over the cable.

This, however, would prove not to be the case.

The Germans now felt they had enough U-boat power to end the war before the Americans could intervene, but they still had to prepare for possible U.S. involvement. The only way to prevent U.S. entry into the war was to somehow distract the United States.

Zimmermann was instructed to check out the possibility of an alliance with Mexico in case the United States abandoned neutrality. Some officials in the German government believed that Carranza might be open to the idea after the Veracruz incident and Pershing’s expedition into Mexico had strained relations with the United States.

Germany Unleashes U-Boats, and the Telegram Goes Public

Over the continued objections of Ambassador Bernstorff and several other high-ranking officials, Germany decided on January 9, 1917, to begin unrestricted submarine warfare. Proponents of the U-boat policy believed it would help them win the war in six months.

Kaiser Wilhelm gave his authorization the next day, and February 1 was selected as the date on which the U-boats would begin this next phase of the war.

Although Zimmermann was sure that Wilson would not budge from his neutrality position (due in part to his recently being reelected on the slogan “he kept us out of war”) the foreign minister still had to be prepared in the event Wilson reversed course.

Zimmermann proposed to his colleagues that in return for Carranza going to war with the United States, any alliance with Mexico would include Germany’s assistance in recovering territory taken from them after the Mexican-American War in 1848. His proposal was approved, and he was told to proceed.

Knowing that Bernstorff had received permission to use the State Department cable, Zimmermann had the coded message delivered to the U.S. embassy in Berlin. It was then transmitted by diplomatic cable to Copenhagen before being wired to London and eventually to Washington.

This roundabout route was used because Germany no longer had cables in the Atlantic and because there was no direct wire from Denmark to the United States. Therefore, the message was sent from Copenhagen to a relay station on the westernmost point of England, where it was intercepted by the Room 40 codebreakers.

The State Department received the telegram on January 17 and delivered it to Bernstorff the following day. He then forwarded it to Heinrich von Eckhardt, the German ambassador to Mexico, on January 19 with instructions to keep its contents secret until further notice. Once decoded, the telegram read:

We intend to begin unrestricted submarine warfare on the first of February. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you.

You will inform the president [of Mexico] of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves.

Please call the president’s attention to the fact that the unrestricted employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England to make peace within a few months. Acknowledge receipt.

Zimmermann

Still hoping to arrange a peace settlement and unaware of Germany’s most recent decision regarding the use of its U-boats, Wilson appeared before the Senate on January 22 and delivered what would become known as his “peace without victory” speech.

He appealed to all nations involved in the war to settle the dispute with no actual winner being declared. On January 31 a distraught Bernstorff reluctantly delivered the notice of Germany’s intent to use unrestricted submarine warfare to Lansing at the State Department.

Eckhardt had originally been instructed not to deliver the alliance proposal to Carranza until it was certain the United States was going to war, but Zimmermann now doubted that Wilson would fail to react and telegraphed Eckhardt on February 5 with a message to proceed.

The telegram’s mention of Japan referred to Germany’s hope to get Japan out of the war. Previous attempts to arrange a separate peace between Germany and Japan, which was fighting on the side of the allies, had been attempted but failed. Zimmermann hoped that Mexico and Japan would form an alliance and then Mexico would be able to mediate peace between Japan and Germany.

Releasing the Telegram: A Dilemma for Cryptographers

Adm. William “Blinker” Hall, the British director of naval intelligence, was faced with a dilemma. His Room 40 cryptographers had intercepted Zimmermann’s telegram to Bernstorff, but knowing they would have to admit to having spied on American diplomatic traffic, he was unprepared to reveal what had been uncovered.

But with seemingly no end to the war in sight and the Americans continuing to stand on the sidelines, Hall decided on February 5 that the time had come to notify his superiors of the intercepted cable.

Hall told them that the decoding was not yet complete and he needed more time before notifying the Americans of the telegram’s existence. The bulk of the telegram had already been deciphered, and Hall clearly understood what it suggested, but he was not yet ready to reveal its contents to the American government.

What Hall really needed was time to find a way in which to deliver the news to Wilson without divulging the fact that the British had been intercepting messages sent over American cable wires.

Knowing that Bernstorff would have relayed the message to Eckhardt using the commercial telegraph system, Hall also knew a duplicate copy would exist in the Mexico City telegraph office.

The Bernstorff-to-Eckhardt copy would have slight differences in date, address, and signature from the original sent by Zimmermann to Bernstorff. If this copy could be obtained and made public, it would appear as if it had been intercepted somewhere between Washington and Mexico. On February 10 a British agent in Mexico known only as “Mr. H” was able to bribe an employee of the telegraph office and secure a copy of the message.

British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour showed the cipher-text to U.S. Ambassador Walter Page during a February 23 meeting. The next day, Page cabled Secretary of State Lansing with news of Bernstorff’s telegram to Mexico. Page, known to be extremely pro-British and often criticized by those back home for not vigorously defending U.S. interests, had to explain how the British came up with the telegram.

In his cover letter, Page wrote somewhat untruthfully that the British had “made it their business” to obtain copies of Bernstorff’s commercial telegrams to Mexico on a regular basis. The telegrams would be sent back to London for decoding, he wrote, thus accounting for the delay in notifying Washington. This explanation allowed the British to keep secret their monitoring of American cable transmissions.

As Wilson was addressing Congress that Monday, seeking passage of a bill allowing Navy gunners on merchant ships, news came over the wire that another British liner, the Laconia, had been torpedoed by a German U-boat.

The next day, February 27, Secretary of State Lansing showed Wilson the original encrypted version of the Zimmermann-to-Bernstorff telegram sent over the State Department cable.

Although he had been advised against releasing the Zimmermann telegram at this time, Wilson decided to release it the next morning. His decision came after receiving word that Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin was planning to lead a filibuster against the armed ships bill. The President hoped that the telegram would convince lawmakers to approve the bill to protect American lives at sea.

The March 1 New York Times headline read:

Germany Seeks Alliance Against US;

Asks Japan and Mexico to Join Her;

Full Text of Her Proposal Made Public.

That same day, the House passed the armed ships bill 403-13, but it died in the Senate, where Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts questioned the authenticity of the telegram. Although Zimmermann’s name was clearly shown on the original telegram, many lawmakers and private citizens still believed it to be a hoax perpetrated by the British in order to entice America into the war.

Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina declared the telegram an outright fraud, asking: “Who can conceive of the Japanese consorting with Mexico and the Germans to attack the United States? Why, Japan hates Germany more than the devil is said to hate holy water.”

Zimmermann, however, surprised everyone when on March 3 he admitted to having been the actual author of the telegram.

The next day, with the filibuster successfully completed, the U.S. Senate went out of session without passing the armed ships bill. Wilson was enraged. Calling the filibuster the act of “a little group of willful men, representing no opinion but their own,” Wilson used his executive authority and ordered all American ships to be armed and ready to fire on any hostile vessel.

On March 20, after German U-boats sank three American ships, Wilson met with his cabinet, where a majority called on him to declare war. Former President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed: “If he does not go to war I shall skin him alive.”

On the night of April 2, Wilson asked Congress to consider the recent actions taken by Germany to be acts of war against the United States and its people, adding that the Zimmermann telegram was proof of the German government’s intent to “stir up enemies against us at our very doors.” Having attempted to stay neutral throughout the course of the war, even playing peacemaker at times, the United States formally declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917.

Postscript

Zimmermann’s alliance proposal did reach the desk of Mexican President Carranza, but it was officially rejected once a military commission determined that there would be no benefit in accepting it. The commission ruled, among other things, that Mexico did not have the military strength to engage in a war with the much stronger United States.

The Japanese prime minister, Count Terauchi, issued a statement denying Japan had been contacted about any such proposal and added that they would have replied with “indignant and categorical refusal” if they had been.

Jay Bellamy is an archives specialist in the Research Support Branch at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, and a frequent contributor to Prologue.

Note on Sources

The Zimmermann telegram is in General Records of the United States, Record Group (RG) 59, National Archives at College Park, MD (NACP). It can also be found in the National Archives online catalog at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/302025; the original decipher of the telegram is at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/302024. A lesson plan about the Zimmermann telegram is online at www.archives.gov/education/lessons/zimmermann/. The telegram is also included in a list of 100 milestone documents: http://ourdocuments.gov/.

The dispatch sent from Admiral Mayo to General Zaragoza during the Tampico incident is located in Navy Subject Files, entry 464B, file code WE-5, Naval Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library, RG 45, NACP.

The report of the Chief Inspector for the Bureau of Explosives concerning the Black Tom explosion is in Entry 15, Records of the Armed Services Explosives Safety Board, Records of Interservice Agencies, RG 334, NACP.

Embassy dispatches can be found in the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) volumes for 1914 and 1917.

The opening quotation is taken from “The Zimmermann Telegram of January 16, 1917, and its Cryptographic Background,” located in Records of the National Security Agency/Central Security Service, RG 457, NACP.

Secondary sources consulted include Chad Millman, The Detonators (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2006) and Barbara Tuchman, The Zimmermann Telegram (New York: Viking Press, 1958).