Our First Preservation Program

Fall 2017, Vol. 49, No. 3 | The Historian’s Notebook

By Jessie Kratz

The National Archives Preservation Programs had been working diligently to protect, preserve, and make accessible federal records almost since the creation of the agency in 1934. In fact, the Archives created the Division of Repair and Preservation on October 1, 1935, under the direction of its first chief, Arthur Kimberly, considered one of the leading authorities on paper preservation at that time.

Within the first year, the division’s staff grew to include a senior scientific aid, a stenographer, and four cleaning clerks. This small division faced the monumental task of preserving an enormous influx of federal records. Within its first five years, the National Archives received more than 300,000 cubic feet of records, which would have nearly hit the building’s storage capacity had the inner courtyard not been converted into stack space in 1937.

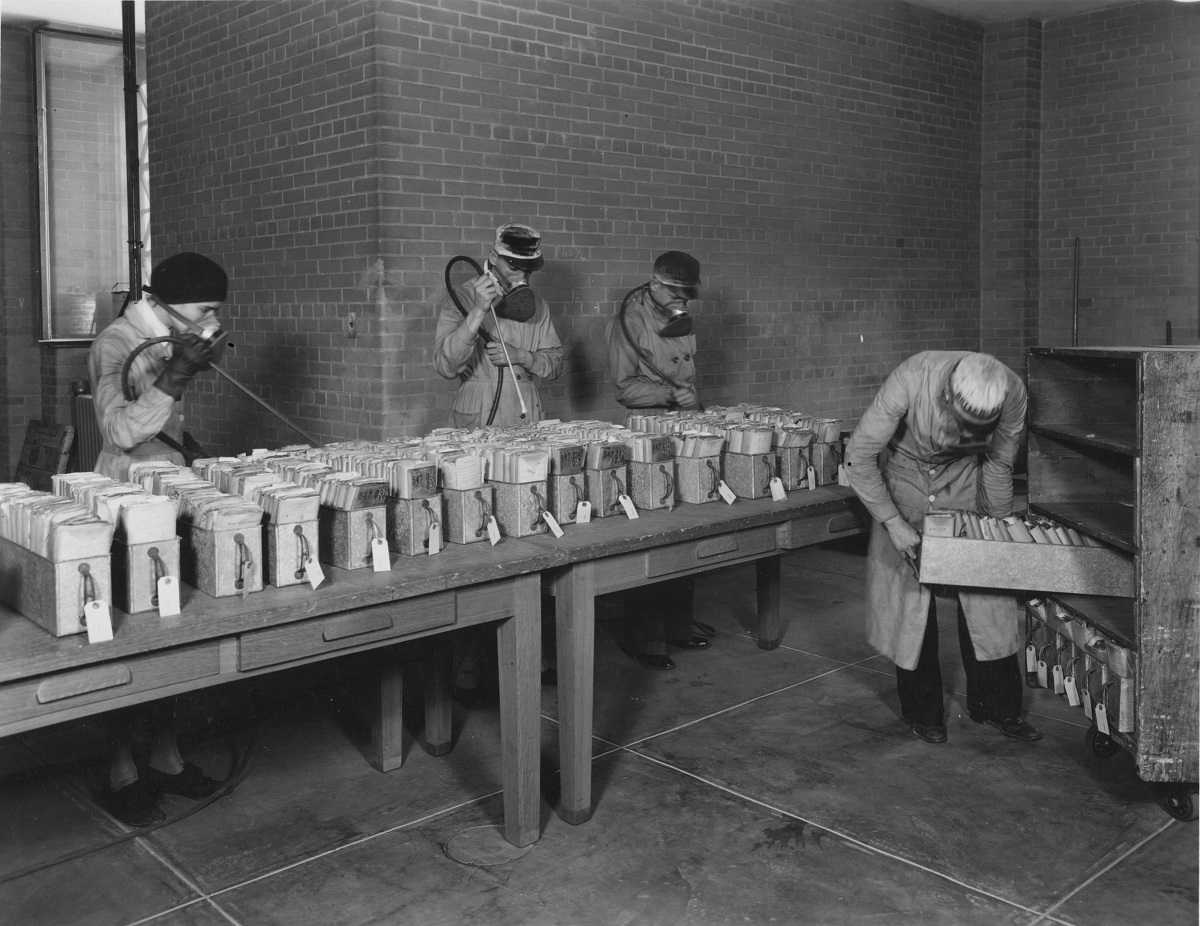

As new records were transferred to the National Archives, they went straight to the Document Conservation Lab for fumigation. Before the National Archives existed, governmental records were often kept in improper storage areas and accumulated mold, silverfish, insects, and other vermin. To rid the records of these infestations, the Archives installed a six-ton fumigation chamber capable of handling 300 cubic feet of records at a time (which turned out to be insufficient because they soon added a second).

Next, the records were cleaned. However, cleaning each individual document would have been prohibitively time consuming, so it was done en masse. Staff even developed a cleaning process using specially designed air guns.

For records of concern, staff had to repair, humidify, and flatten them. Sometimes this included lamination, which conservators have since learned can be detrimental to the documents.

And, as if staff wasn’t kept busy enough, they also monitored stacks for appropriate temperature and humidity levels, and made sure there wasn’t too much dust or sulfur dioxide in the air. This wasn’t an easy task since air quality in the stacks varied widely in the building’s early years.

Today, the Document Conservation Laboratory is still in its original location in the National Archives Building with additional labs in College Park and St. Louis. With years of research on best practices in preservation, the staff—which now numbers 55—use the most up-to-date techniques to continue to ensure America’s documents are preserved and accessible for generations to come.