Abraham Lincoln and Herbert Hoover

The Bond of a Simple Engraving

Fall 2017, Vol. 49, No. 3

By Timothy Walch

Abraham Lincoln and Herbert Hoover were, in many ways, alike.

Both were born in primitive circumstances on the frontier of a new nation. Their birthplaces were similar even though they were born 65 years apart. Hoover’s board and batten cottage had no more amenities than did Lincoln’s log cabin.

They were also men driven to succeed in spite of the lowly circumstances of their births. Lincoln was self-educated but became one of the foremost attorneys of his time. Hoover bulled his way into the first class at Stanford University and became the most successful mining engineer of the age. They were self-made and owed nothing to anyone for their success.

And neither man was content with his success. Each sought the presidency in a quest to improve the lives of ordinary Americans yet neither man had the opportunity to implement his vision for the nation. Instead, each faced the most devastating crisis of his respective century, sweeping up his presidency in circumstances beyond his control.

That is where the similarities end, however. Lincoln is remembered as the savior of the nation during the Civil War, while Hoover is blamed for the worst economic crisis, the Great Depression, in American history. Lincoln is considered one of our greatest presidents, and Hoover is tarred as one of the worst.

How could Lincoln ever have been much of an influence on Herbert Hoover? The evidence is in the Hoover Presidential Library in the president’s hometown of West Branch, Iowa.

To say that Lincoln’s philosophy and values were an important influence on Herbert Hoover is something of an understatement. His generation was born in an era of Lincoln worship. All children—including young Bert Hoover—were encouraged to learn from the life of Father Abraham.

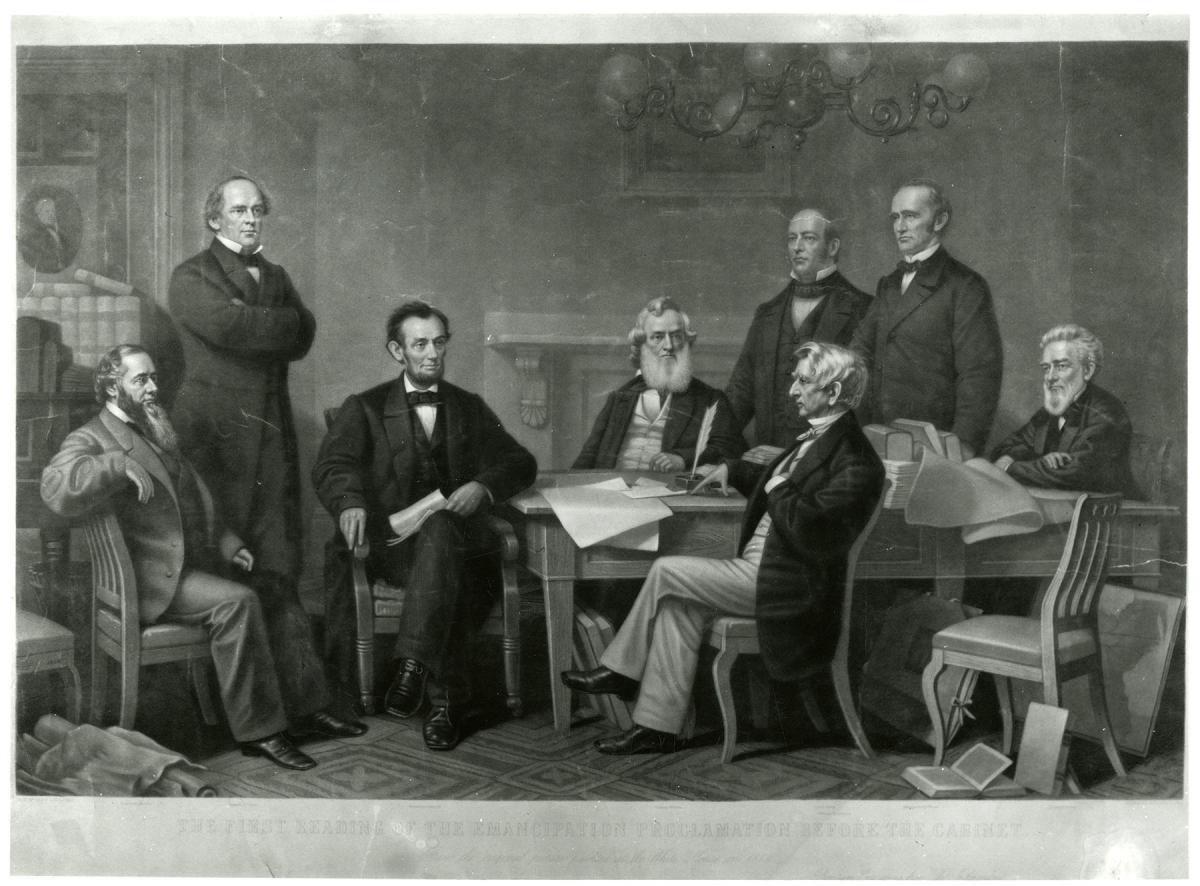

The Hoover family, however, may have been a bit more devoted to Lincoln than most. Later in life, Hoover would recall that only one picture had hung in his little birthplace cottage. That picture was an engraving of Lincoln, surrounded by his cabinet officers, as he shared with them his draft of the Emancipation Proclamation.

There was not much else to look at in that cabin, so a bright young boy like Bert Hoover must have studied that picture intensely. Not surprisingly, the picture later became a prized possession—Hoover’s one material link to his father, grandfather, and the Great Emancipator. Hoover had it restored and hung it in his home in Washington when he served as Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s.

And that picture moved with Hoover when he entered the White House in 1929. Using his beloved engraving as his guide, Hoover refurbished the Lincoln cabinet room and sought out the furnishings that had once graced this room in the Lincoln administration.

Hoover directed the White House staff to search for the furniture that matched Carpenter’s print. They found the desk and the chair used by Lincoln. And, in a place of honor above the marble mantel, Hoover hung his Carpenter engraving.

Throughout his troubled presidency, Hoover found solace from sitting in the Lincoln study. And used the room to broadcast his Lincoln Day addresses. “It is appropriate that I should speak in this room in the White House where Lincoln strived and accomplished his great service to our country," Hoover told the radio audience in 1931. “His invisible presence dominates these halls, ever recalling that infinite patience that that indomitable will which fought and won the fight for those firmer foundations and greater strength to government by the people.”

Later that year, Hoover rededicated Lincoln’s tomb in Springfield, Illinois. “Time sifts out the essentials of men’s character and deeds, and in Lincoln’s character there stands out his patience, his indomitable will, his sense of humanity of a breadth which comes to but few men.” These were two qualities that Hoover cherished as he faced the challenges of the Depression.

Just four days before the election of 1932, Hoover traveled to Lincoln’s home in Springfield and linked himself to Lincoln. “No man in my position,” Hoover told a national radio audience, “can fail to gain inspiration and courage from the courage and intelligence and the unswerving fidelity with which Abraham Lincoln met the overwhelming difficulties that threatened the very existence of our Union.”

Herbert Hoover died on October 20, 1964, in his bedroom at the Waldorf Towers in New York City. He was 90 years old. He had seen enormous changes in his long life, but one of the few constants was a picture that hung on a wall just outside the room where he died. There, in a simple frame, was that engraving of Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation. It had hung on the wall of his birthplace and it was with him at the end; it was the one possession he carried from cradle to grave.

Hoover was deeply influenced by the life and philosophy of Abraham Lincoln and when he became president himself, he eagerly sought comfort in Lincoln’s own White House study. Over and over again, as Hoover fought his own war on a thousand fronts, he reminded himself of Lincoln’s qualities—patience and steadfastness.

So Herbert Hoover, like so many other presidents, looked to the Great Emancipator for wisdom and advice. Virtually all the men who occupy the presidency have come to revere Lincoln. Hoover was no different from them; Lincoln was his guide.

Timothy Walch served as director of the Hoover Presidential Library from 1993 to 2011 and as editor of Prologue from 1982 to 1988. He is the author or editor of 20 books including four volumes on the life and times of Herbert Hoover. He received his B.A. from the University of Notre Dame and his Ph.D. from Northwestern University.