Free Speech on Trial

Eugene Debs at Canton, Ohio

Winter 2017–18, Vol. 49, no. 4

By Glenn V. Longacre

On a sultry afternoon in 1918, the tall, lanky Hoosier walked up the bandstand’s steps and surveyed the growing crowd gathered in Nimisilla Park in Canton, Ohio, on Sunday, June 16. They had come to hear the keynote speech at the Buckeye State’s annual Socialist Convention and Eugene V. Debs Picnic.

Eugene V. Debs himself, the country’s leading socialist and labor organizer, and four-time candidate for President, waited for his turn to address the crowd.

In the crowd, estimated in size between 250 and more than 1,000, were several hundred socialists, sympathizers, and interested bystanders. But the crowd also included a number of individuals who were decidedly not sympathizers or well-wishers, and their presence did not bode well for the featured speaker that day.

Eugene Victor Debs was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, on November 5, 1855. His parents were Daniel and Marguerite Debs, immigrants from the Alsace region in France. Of six children born to Daniel and Marguerite, Eugene was the oldest son. Debs’s only brother, Theodore, was born in 1864. Theodore idolized his brother and later became his devoted assistant.

By all accounts, Debs was a good student, but the excitement of working on the railroad was too much for the youngster to ignore. In 1870 at age 14, Debs left high school against his parents’ protestations and worked for the Vandalia Railroad in Terre Haute as an unskilled paint scraper at 50 cents a day. Within a year he became a fireman for the railroad.

In 1875 Debs, now unemployed, accepted a position with H. Hulman & Company in Terre Haute. That year also saw his initial foray into the labor movement, when he became a member of the town’s fledgling lodge of Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen. Debs was a charter member and was elected recording secretary. His acuity in organization and growing talent for public speaking fared him well, and he rapidly advanced in the organization’s hierarchy.

Throughout the 1880s, Debs’s interest in organized labor activities brought him into contact with central Indiana’s politics, where he aligned himself with the Democratic Party’s platform. Debs’s popularity was so great that he was elected to the state legislature for one term. The following year, Debs married Katherine Baur, the daughter of a well-to-do Terre Haute couple.

By 1894, Debs had resigned from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen over internal disagreements about the organization’s philosophy and direction. Debs believed that small, disparate, class- and trade-driven unions possessed little power to influence social change for their members.

Debs’s New Union Has Its First Test

Instead, Debs reasoned that his recently formed American Railway Union (ARU) was the model organization to unite all railway workers in a powerful, national, and united voice in the industry. Debs and the ARU’s first test came early that year, when he and other ARU members were victorious in a strike against the Great Northern Railway, which ran from St. Paul to Seattle. When Chicago railroad workers in George Pullman’s company went on strike over wages later in the spring and summer, Debs was confident that his ARU was equal to the task.

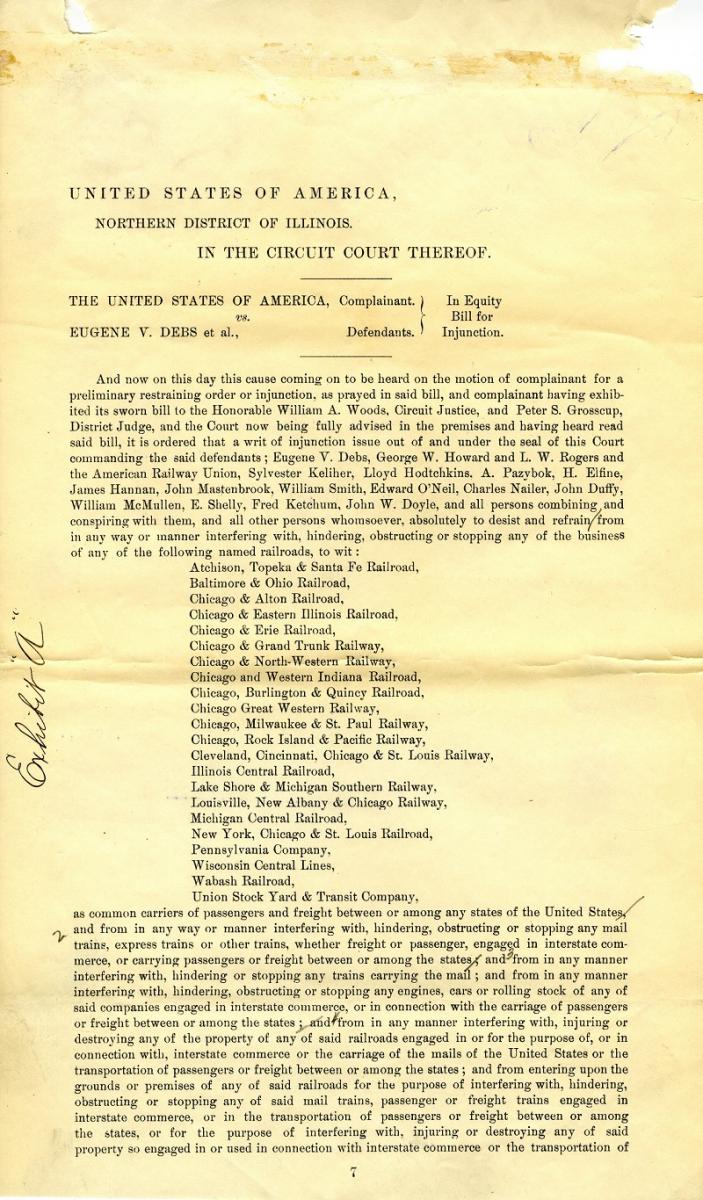

On July 2, 1894, federal judges in Chicago issued an injunction prohibiting Debs and the strikers from interfering with the regular transmittal of mail via the railroad. As the strike spread and the injunction failed to halt the strikers, Pullman and other railroad owners called on President Grover Cleveland for support. The President sent in Regular Army troops to quell the violence and subdue the strikers. What became known as the Pullman Strike turned into a failure for Debs and destruction for the ARU. Convicted of violating the injunction, Debs was sentenced to six months in jail.

While serving his prison term, Debs reexamined his political philosophy and declared himself a socialist. By the time Debs was released from prison in November 1895, he had become a nationally recognized celebrity and political force. The socio-political beliefs that had attracted Debs and the other members to establish the defunct ARU now gathered to form the new Socialist Party with Eugene Debs as its head. Debs’s stature and influence among the new party’s members was undeniably great, and in 1900 he accepted their nomination to represent the party in the presidential election. Debs’s popularity was so great that he dominated the party leadership for the next two decades, and was nominated as their perennial candidate in the 1904, 1908, 1912, and while in prison, the 1920 presidential elections.

Now a Celebrity, Debs Seeks Presidency

Even while Debs immersed himself in socialist politics, he still sought the formation of a labor union that encompassed his goals of inclusivity for all workers. In 1905 in Chicago, Debs was a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also known as the Wobblies. The IWW philosophy coincided with Debs’s views that all workers, regardless of class, had to be united in one powerful union in their struggles against capitalism.

With the approach of the First World War, Debs’s and the Socialist Party’s opposition to American involvement in the war was largely consistent with mainstream America’s desire for neutrality. U.S. involvement in what was seen by many as a European affair was strongly opposed by a majority of Americans. By 1917, however, as American involvement became a reality, the country’s attitude towards war shifted to committed and patriotic participation.

Debs’s and the Socialist Party’s platform against American involvement, however, continued unchanged. They saw American involvement as a class struggle wherein workers were to be sacrificed for corporate benefit and greed. As the United States moved onto a war footing, socialists like Debs enthusiastically voiced their opposition at speaking engagements and through the press. Their audience, however, grew smaller, and public opinion to a large degree turned against the socialists.

A month following the American entry into the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Espionage Act of 1917 into law. This wide-ranging act, still in existence today, made it a federal crime to interfere with, among other things, the Selective Service Act or military draft.

By the time Debs mounted the bandstand in Canton’s Nimisilla Park to give his antiwar speech a year later, the Espionage Act had become the U.S. Government’s effective countermeasure to organized dissent. With the act, federal judicial agencies wielded greater power to interpret violations of the law and indict its opponents. Debs had not failed to recognize this threat as he arrived in Canton to address the state’s socialists.

Debs Gives Speech Extolling Socialism

The program began shortly after 1 p.m., when Allen Cook, leader of Canton’s Socialist Party, and a “warrior in the grand army of liberation,” as Debs later described him, read the Declaration of Independence. Marguerite Prevey, a wealthy Akron socialite, then took the platform to introduce Debs. An ardent radical herself, Prevey often financially supported socialist speakers, including Debs, as they traveled around the Buckeye State.

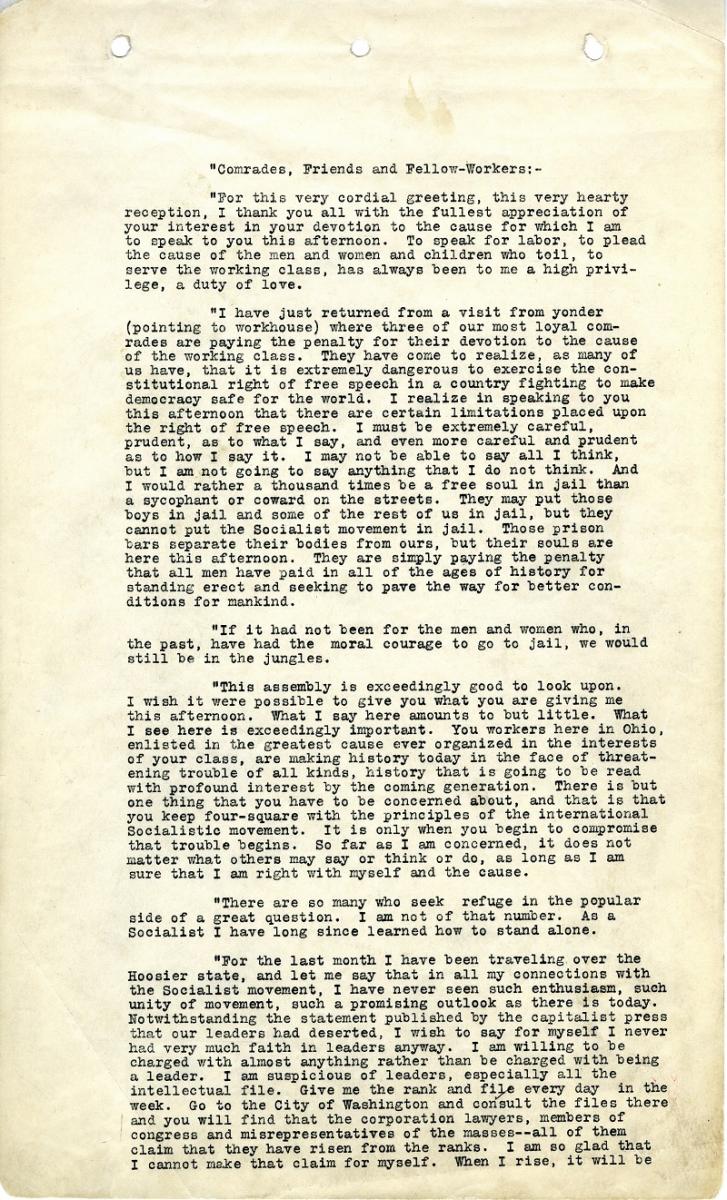

Following a raucous applause, Debs addressed the gathered crowd. He first pointed to the Stark County Work House that sat on the periphery of the park. Inside, he noted, were three prominent antiwar activists and fellow socialists, Charles Ruthenberg, Alfred Wagenknecht, and Charles Baker, who had been convicted the previous year for inciting resistance to the draft. Debs, in his dynamic speaking voice, prefaced his coming remarks by telling the crowd that he had to be “extremely careful, prudent, as to what I say, and even more careful and more prudent as to how I say it.” He added that “I may not be able to say all that I think; but I am not going to say anything that I do not think.”

Debs’s caution was warranted.

In the crowd were U.S. Department of Justice agents. Their roles were to gather the evidence that potentially could be used in initiating criminal proceedings against Debs and the other speakers. Among the agents was James V. McCann, a soldier stationed at Camp Sherman near Chillicothe, Ohio, whose task was to photograph Debs delivering his remarks. In addition to McCann, Virgil Steiner, a stenographer employed by the Department of Justice, was under orders to record as much as possible of Debs’s speech. Debs’s lengthy speech included many of his standard arguments and talking points for supporting the socialist cause. Regarding the war, Debs decried America’s involvement, saying, “They have always taught you that it is your patriotic duty to go to war and slaughter yourselves at their command. You have never had a voice in the war. The working class who make the sacrifices, who shed the blood, have never yet had a voice in declaring war.” Observers noted that the crowd responded throughout his speech with moments of enthusiastic applause.

Debs, rightly concerned that he might run afoul of the government’s crackdown on antiwar protests, believed that his speech was tempered with sufficient restraint to avoid charges of sedition, but he miscalculated. The Espionage Act had lowered the threshold for overstepping the legal boundaries of antiwar discourse.

Federal Officials Plan Debs’s Arrest

When news of Debs’s speech reached federal prosecutor Edwin Wertz at the U.S. District Court in Cleveland, plans were placed in motion to arrest and indict Debs on charges of sedition under the act. Two weeks later, on June 30, as Debs traveled through Cleveland to another speaking engagement, he was arrested and escorted to jail. A 10-count indictment, filed the day before, charged the socialist and labor leader with, among other things, “unlawfully, willfully and feloniously cause and attempt to cause and incite and attempt to incite, insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny and refusal of duty, in the military and naval forces of the United States.”

Following the indictment, Debs fully recognized the severity of the charges. In a letter to a friend on July 6, 1918, he confided, “I am expecting nothing but conviction under a law flagrantly unconstitutional and which was framed especially for the suppression of free speech.”

With his bail paid by Marguerite Prevey and a Cleveland comrade, A. W. Moskovitz, Debs was released. He returned home to Terre Haute to await trial. The trial began on September 10, 1918, in the U.S. District Court in Cleveland.

The trial itself was swift considering its high-profile defendant. Witnesses for the prosecution testified. Exhibits were produced, including copies of the speech recorded by Steiner and the three photographs taken by McCann that not only showed Debs giving the speech but also, with a country in the throes of a world war, a bandstand devoid of any patriotic decoration. After just two days, on Wednesday, September 12, the prosecution rested its case.

In a move that startled both the judge and prosecution, Debs’s attorney declined to call the defense witnesses. Instead, they chose to let Debs himself address the jury. Knowing that his conviction was inevitable, Debs decided to use the opportunity to address the jury as a platform for the socialist cause and the right to freedom of speech. Midway through his lengthy discourse, Debs defended his right to deliver an antiwar speech at Canton, “There is not a single falsehood in that speech. If there is a single statement in it that will not bear the light of truth, I will retract it. I will make all of the reparation in my power. But if what I said is true, and I believe it is, then whatever fate or fortune may have in store for me I shall preserve inviolate the integrity of my soul and stand by it to the end.”

Debs Heads to Prison As World War I Ends

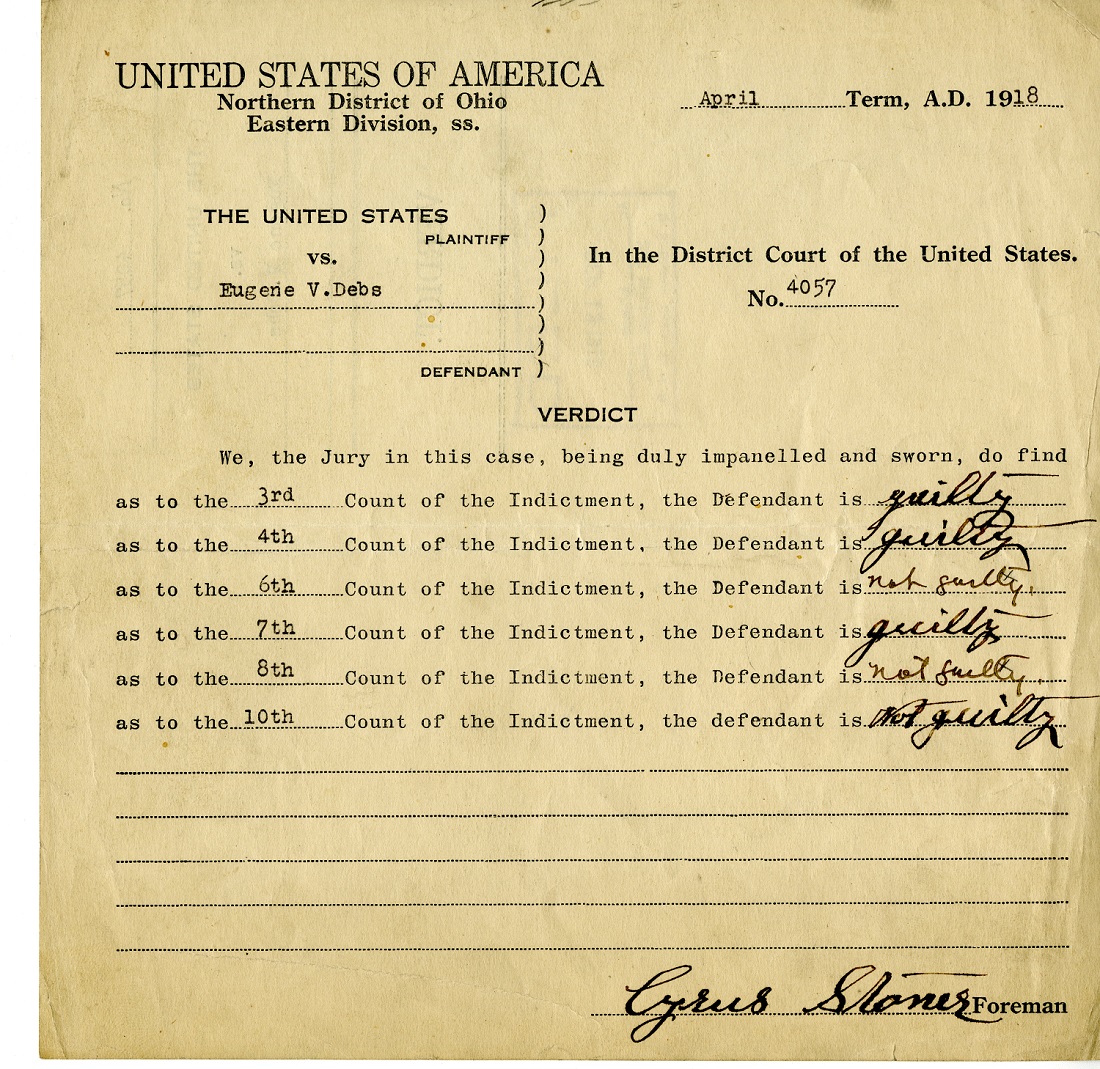

Debs concluded his address telling the jury, “My fate is in your hands. I am prepared for the verdict.” With that the jury retired to deliberate. Debs’s fate, however, was little in doubt. The jury returned after a lengthy recess and read the verdict: guilty on three counts.

After a day’s recess, Debs returned for sentencing, and Judge David Westenhaver sentenced him to 10 years in prison.

Debs remained free while his attorneys appealed the verdict to the U.S. Supreme Court. As he and his followers waited for the court’s decision, the First World War ended on November 11, 1918. The war’s end, however, did not soften the judiciary’s position on Debs’s conviction. On March 10, 1919, the Supreme Court rejected his appeal. After almost seven months of waiting, Wertz ordered the unrepentant socialist to report to Cleveland to begin his sentence.

Debs was incarcerated at the West Virginia Penitentiary in Moundsville. The prison’s warden, Joseph Terrell, at first hostile to Debs and his socialist philosophy, quickly recognized that the elderly man now standing before him was in no way a threat to his authority. Similarly, Debs assured Terrell that he would not preach socialism to his fellow inmates. The warden quickly grew to like Debs and within the limits possible made life at Moundsville Penitentiary as comfortable as possible.

“Since I had to be imprisoned I congratulate myself,” Debs wrote his brother, Theodore, “upon being here for it is in all regards the best I have ever seen.” Shortly thereafter, however, he was transferred in June 1919 to the U.S. Penitentiary in Atlanta.

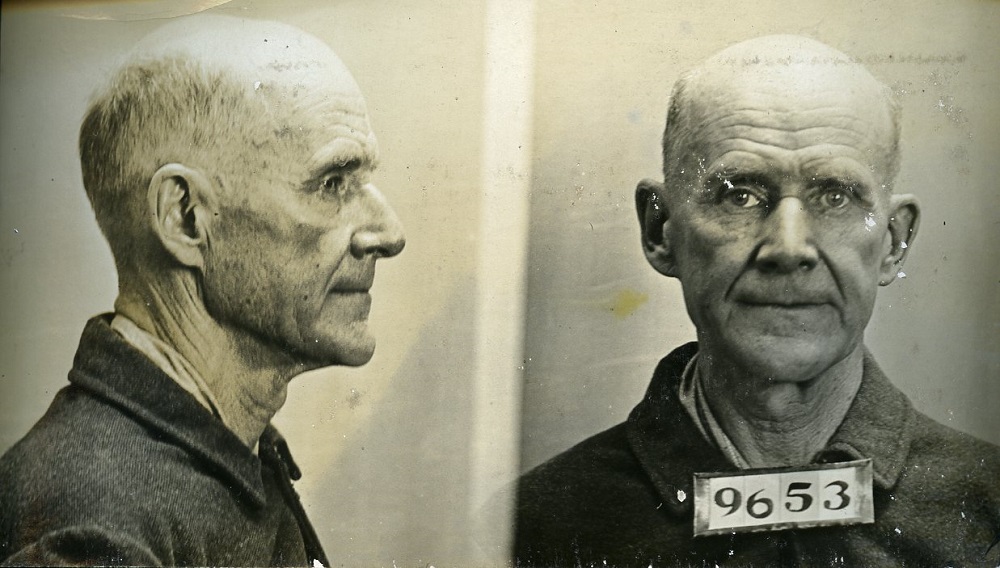

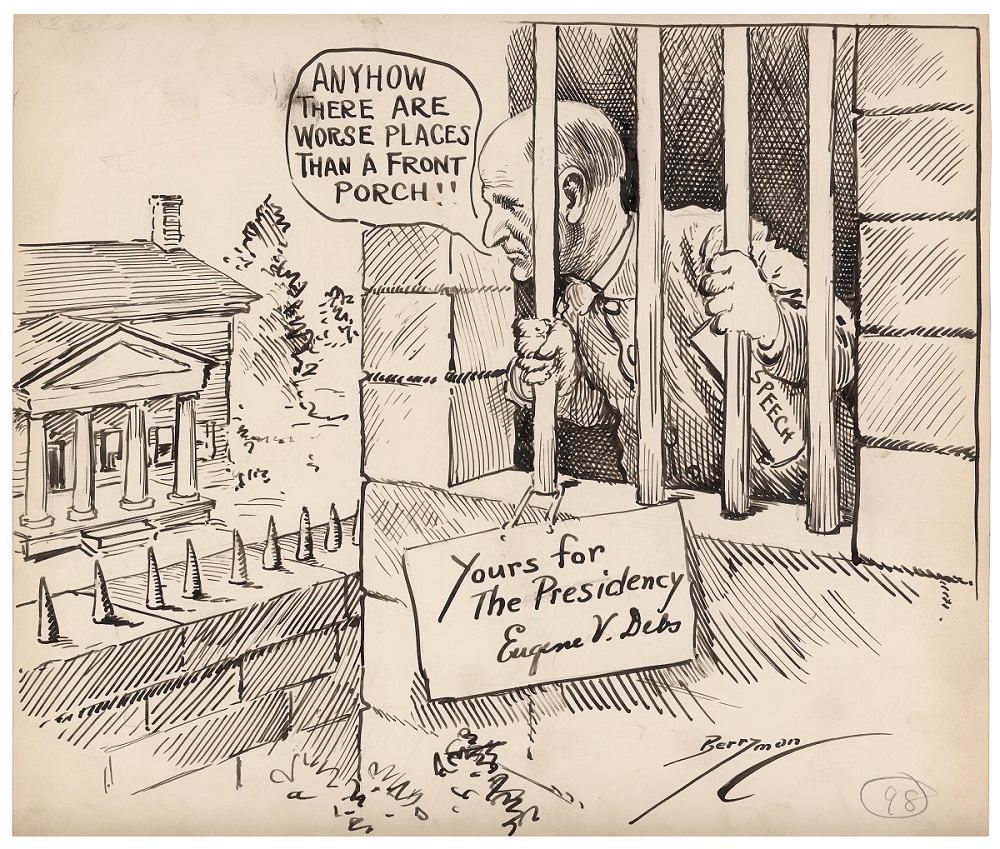

As Convict 9653, Debs Again Runs for President

As the 1920 presidential election neared, Debs, or Convict 9653, declared his candidacy on the socialist ticket for President for a fifth time. While his supporters campaigned in the streets, Debs campaigned from behind cell bars. His socialist message still appealed to many Americans, and as the returns were tallied, Debs received almost a million votes. With the war over and a newly elected, and sympathetic, Republican President, Warren Harding, in the White House, there were appeals to commute Debs sentence to time served.

President Harding commuted Debs's sentence to time served, and Debs was released from the Atlanta Penitentiary on Christmas Day, 1921. As he walked away from the prison, accompanied by his brother, Theodore, and other supporters, he heard a growing roar of applause that emanated from behind the barred windows. Debs paused, turned back to face his admirers, removed his hat, acknowledged their ovation, and wept.

Debs boarded a train for Washington, D.C., where he briefly met with President Harding. Afterward he returned home to Terre Haute, where he was greeted by throngs of well-wishers. Debs’s speech and subsequent conviction under the Espionage Act ultimately aided him in delivering the Socialist Party’s antiwar platform to a larger audience, but his age and prison’s deleterious effects on his already fragile health exhausted the orator’s stamina and drive.

With Debs’s health in decline, the Socialist Party also saw a decline in its popularity. In 1926 Debs traveled to Lindlahr Sanitarium in Elmhurst, Illinois, for recurrent medical treatment. He died of heart failure there on October 20, 1926. Debs’s remains were cremated. He is buried in Terre Haute’s Highland Lawn Cemetery.

Glenn V. Longacre is an archivist with the National Archives at Chicago. He holds a B.A. in history and an M.A. in public history from West Virginia University. He is the coeditor of To Battle for God and the Right: The Civil War Letterbooks of Emerson Opdycke (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003). Currently, he is editing the memoirs of a soldier who served on the Great Plains with the Sixth West Virginia Veteran Volunteer Cavalry.

Note on Sources

The standard biography of Eugene Debs is Nick Salvatore’s Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1982). The best treatment of Debs’s Canton speech is Ernest Freeberg’s Democracy’s Prisoner: Eugene V. Debs, The Great War, and The Right to Dissent (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008).

The National Archives at Chicago’s holdings include several prominent federal cases in which Debs was a defendant. Debs was convicted for not complying with the injunction issued during the Pullman Strike is The United States v. Eugene V. Debs, et al. The case is located in Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States, Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division, U.S. Circuit Court, Chicago, Civil Case Files, 1871–1911, Equity Case 23421.

Debs was convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917 in The United States v. Eugene V. Debs. The case is located in Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States, Northern District of Ohio, Eastern Division, U.S. District Court, Cleveland, Criminal Case Files, 1912–1987, Case 4057 (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/2765897). Debs’s incarceration at the U.S. Penitentiary, Atlanta, is documented in Inmate Case Files, 1880–1922 (Inmate Case File 9653), in Record Group 129, Records of the Bureau of Prisons, 1870–2009, held at the National Archives at Atlanta (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/867008).

The case file for United States v. Alphons J. Schue, Charles Ruthenberg, Alfred Wagenknecht, and Charles Baker (the comrades referred to in Debs’s Canton speech held in the nearby Stark County Work House) is located in Record Group 21, Records of District Courts of the United States, Northern District of Ohio, Eastern Division, U.S. District Court, Cleveland, Criminal Case Files, 1912–1987, Case 3873. Coincidently, after his release Charles Ruthenberg founded the American Communist Party.

There are several collections of Debs’s papers around the United States. The primary collection, however, is at Indiana State University’s Cunningham Memorial Library’s Special Collections Department in Terre Haute. A portion of Debs’s papers appear as The Papers of Eugene V. Debs, 1834–1945 by J. Robert Constantine, late professor of history at Indiana State University. Constantine also published a three-volume Correspondence of Eugene V. Debs, which comprised a selection of 1,500 letters from the manuscript collection. A more concise edition of Debs’s letters is found in Constantine’s Gentle Rebel: Letters of Eugene V. Debs (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1955).

Debs’s residence in Terre Haute is now home to the Eugene V. Debs Foundation and Museum. Likewise, Canton’s residents are justifiably proud of Nimisilla Park, where Debs voiced his most famous antiwar speech. Still in existence, the park’s historical significance was recognized in June 2017, when the Ohio History Connection and city officials dedicated a historical marker.

The author would like to thank Leo Belleville, Doug Bicknese, Maureen Dunn, Rob Richards, and Sarah Rogers for their assistance on this article.