Ron Chernow: Grant

Winter 2017–18, Vol. 49, No. 4 | Authors on the Record

Interview by Keith Donohue

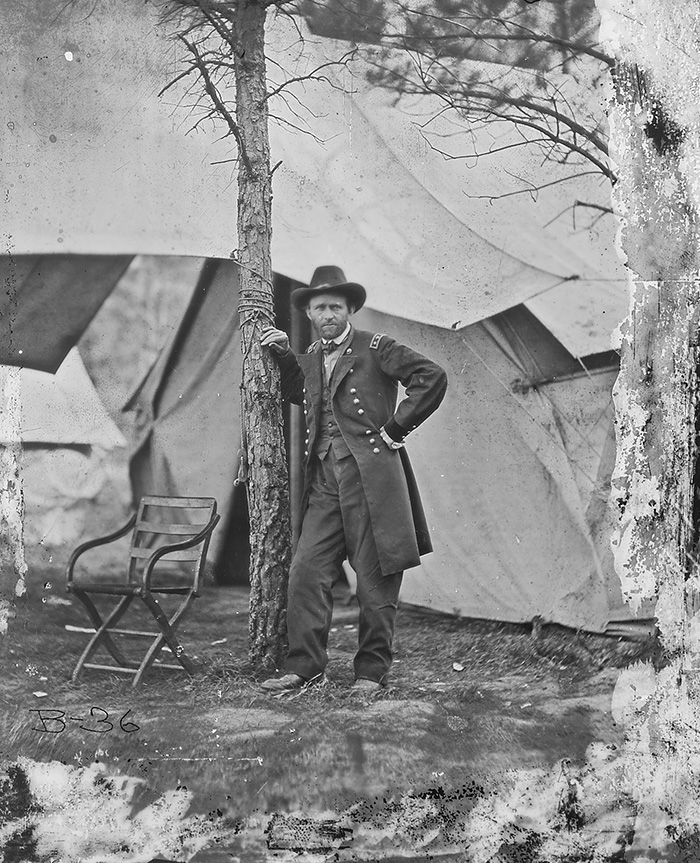

As he was dying, Ulysses S. Grant wrote to a friend, “I am a verb. Instead of a personal pronoun.” The life of Ulysses S. Grant was one of action and motion, yet it reads like an American tragedy. From humble beginnings, Grant made it to West Point, returned home to failure, suffered with drink, and yet triumphed in the Civil War. And then he had the misfortune to be a two-term President in an era of easy corruption. After a triumphant tour around the world, he was swindled and lost his fortune, only to find redemption by working with Mark Twain to publish his memoirs.

As he was dying, Ulysses S. Grant wrote to a friend, “I am a verb. Instead of a personal pronoun.” The life of Ulysses S. Grant was one of action and motion, yet it reads like an American tragedy. From humble beginnings, Grant made it to West Point, returned home to failure, suffered with drink, and yet triumphed in the Civil War. And then he had the misfortune to be a two-term President in an era of easy corruption. After a triumphant tour around the world, he was swindled and lost his fortune, only to find redemption by working with Mark Twain to publish his memoirs.

Ron Chernow’s new biography Grant traces the ups and downs of the storied life, including Grant’s efforts to reunite the country after the Civil War while protecting the rights of the newly freed people once bound to slavery. Recipient of the 2015 National Humanities Medal, Chernow is the author of seven books. The House of Morgan won the National Book Award. Washington: A Life won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography. Alexander Hamilton—the inspiration for the Broadway musical—won the American History Book Prize. A past president of PEN America, Chernow lives in Brooklyn.

The National Archives, through the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, funded the documentary edition of the Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. How important was that to your new biography?

I cannot speak highly enough of the Grant Papers, and my one great regret is that I never got the chance to thank the editor, John Y. Simon, in person. What he did in creating those 32 volumes is one of the great scholarly feats in American history of the 20th and early 21st century. This is the third time I’ve done a book where’s there’s been a new documentary edition of the papers completed (or in the case of George Washington, ongoing). When I started writing Alexander Hamilton in 1988, the last Hamilton Papers volume had been published by Columbia University Press. In the case of Grant, the first volume was published in 1967 and the last in 2012, just as I was beginning. I’m grateful to the editors of the papers of Hamilton and Washington, who made me look good. In many ways, however, the Grant Papers constitute my favorite edition.

Before Simon and the folks at Southern Illinois University began to assemble the papers, there had been no edition for Grant. Unlike Washington, which back in the 1930s had a 17-volume edition, though it was much more limited than the extraordinarily ambitious project under way at the University of Virginia. In the case of Grant, this was completely virgin territory. These papers are so enriched not only by having all of the letters and documents Grant wrote and were written to him, but also so many excerpts from letters, diaries, and newspapers commenting on the event at hand. Very often a three- to four-line letter from Grant would be explicated by three to four pages of notes and supplementary material, which really allows the researcher to go as deeply into the life as possible.

You’re not only seeing the life from the inside out, but the editors allow you to see from the outside in. For a biographer having that rounded view is essential, and it was done brilliantly. The scholars who create these editions are the unsung heroes of the profession. They make writers like me look good. I was lucky to have those 32 volumes and 50,000 documents. Shortly before I started, the Grant project moved to the Mitchell Memorial Library at Mississippi State University, where there are another 250,000 documents. John Marszalek has done an extraordinary job in putting the U.S. Grant Presidential Library on the map. It is fantastic that the Ulysses Grant Papers ended up in the Deep South.

Wouldn’t Grant have been pleased?

He was always interested in reconciliation between the North and South, and I think Grant would have been moved by his papers ending up in this most unlikely place. Mississippi was the scene of many of his greatest battles. Grant considered Vicksburg his military masterpiece. Later in life he made the comment that there were many things he would have done differently, except for the Vicksburg Campaign.

How did his desire for reconciliation affect his attitudes toward both the Confederate Army and the freed slaves?

People know the story of Appomattox and the generous terms of surrender Grant laid down. Look back at Union victories at Fort Donelson and Vicksburg, and you’ll see he was similarly magnanimous. Grant said it was important to treat defeated soldiers with respect, not only to win their allegiance but also to make them better citizens. Even when composing his Memoirs under the horrific physical conditions at the end of his life, he was greeting visitors from the vanquished South, like Confederate general Simon Buckner.

He had a very complicated relationship with the South. After Appomattox, he achieved a heroic status as the man who had dealt so respectfully with the Army of Northern Virginia. Yet it was his unwavering desire to protect freed slaves that made him a bogeyman in the eyes of some. During Reconstruction, many in the South resented Grant’s sending Federal troops to protect the four million blacks who had become citizens and those who had won the right to vote. Grant was caught in a contradictory situation: there was no one more eager to heal the wounds and reunite the country, but no one more uncompromising in insisting these four million people would have full rights as citizens. It is the most important untold story in American history.

Talk a bit about how Grant’s thinking on civil rights evolved immediately after the war during the Andrew Johnson administration.

During the Johnson years, Grant served as general-in-chief overseeing the five districts into which the South had been carved. He remained faithful to two ideas. He had promised Robert E. Lee that he would not be prosecuted, even when federal judge John C. Underwood sought to indict Lee and other Confederate leaders for treason. Grant went to President Johnson, who at that point was on the warpath against the Confederate leaders, and threatened to quit because he had pledged his sacred honor. On the other hand, as Johnson adopted an overly lenient policy toward the white South, Grant remained firm and consistent in protecting black rights.

Most Americans don’t know that such a civil rights movement existed. They know all about the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s but have no idea that many of the same things happened in the 1860s and early 1870s. I was surprised myself. I’ll never forget reading an 1867 letter from Phil Sheridan in New Orleans telling Grant that they’d desegregated the streetcars, and it was the first time blacks and whites were riding side by side. Yet all of those extraordinary gains were rolled back and became frozen in the South through Jim Crow laws for almost a century.

The white South was never reconciled to the fact that blacks deserved equal rights and equal justice, and they refused to share power, even in states like South Carolina and Mississippi, where the black population made up the majority. Violence against blacks—and white Republicans—inhibited those trying to exercise the right to vote. It is shocking the extent to which the Ku Klux Klan spread throughout the South and the extent to which so many communities offered open or tacit support. No Southern sheriff would arrest a Klansman, no Southern jury would convict. I commend the Grant Papers for saving and publishing so many of the letters by distraught blacks and white Republicans to Grant, often by not very educated people, sometimes in broken English, but telling letter after letter hair-raising stories of suddenly waking up at night to men in hoods and robes on horseback surrounding the house, terrorizing the family.

Your most recent biographies on Hamilton, Washington, and now Grant don’t shy away from these figures’ almost Shakespearean tragic flaws. Let’s talk about Grant’s drinking problem.

It is so valuable to have all of the letters both signed and anonymous about Grant’s drinking. Books on Grant have been increasingly admiring in recent years, but unlike some, I came to take the drinking seriously. People who have admired Grant have tried to minimize the problem, and when I started the book I thought that would be my approach. But the letters—written by different people at different times—paint a remarkable consistent portrait. While this or that letter may have been maliciously intended or exaggerations sent by a rival, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the drinking wasn’t Grant’s fault.

As a biographer, I go out of my way to include any flaws that I find. Readers are very sophisticated. They know that historical figures—and those in our own times—are all compounds of good and evil. As I recently told the Wall Street Journal, great characters in history can carry the weight of their own defects. What I found in the stories of these great men—Hamilton, Washington, Grant—is that their flaws make them more believable and, ironically, more heroic. Readers suddenly realize this was a person like me, with the same fears and insecurities, yet they managed to do great things. We do a disservice trying to turn them into plaster saints because in so doing we make them both unbelievable and boring.

And how much drama was built in their lives. Washington and Hamilton were very ambitious. By the age of 12, Hamilton is already contemplating his place in history. And in Titan, my biography of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., I recount how he remembered being a teenager working on the docks in Cleveland, thinking “I was after something big.”

Grant was not. He’s really the least self-aggrandizing figure. By the time he graduated from West Point, his ambition was not to be a math teacher at the Academy, but an assistant math teacher. His life before the Civil War seems very narrow. Here was this man who was junior clerk in the family’s leather store. Though he has been harboring these patriotic feelings since leaving the Army, he had no occasion to bring them out. You don’t sense that his mind was fully engaged in the beginning, but experiences during the war and afterwards forced the big issues upon him. By the end of the war as general-in-chief, he has a million men under him. He was two-term President. His life was one of the most extraordinary personal sagas, especially by someone who had experienced repeated business failures and personal hardships.

Abolitionism becomes a major force, shown by recruiting and arming black troops and later protecting the four million freed citizens. By the time he gets to his round-the-world trip in 1877, his mind is so much more active that he becomes a student of the many countries he’s visiting. He’s more intellectually engaged and is forced to give speeches, and surprisingly he’s good at it. He’s completely equal to the task of meeting foreign heads of state. Grant was better read than people imagine, but all sorts of subjects seize his attention as he moves through his life. There’s this profound growth as a person. This is what biography is all about: the impact of experience on personality and character.