Safe for Democracy

Black National Guard Soldiers in the Great War

Winter 2017–18, Vol. 49, no. 4

By Matthew J. Margis

A German raiding party approached the Allied position in the Argonne Forest early in the morning on May 14, 1918. Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts of the 369th Infantry, 93rd Provisional Division, comprised two-fifths of a small observation crew, and shortly after two in the morning Roberts heard a distinctive clipping sound. He quickly realized he was hearing German wire cutters, and he tried to alert the rest of his team by sending off a warning flare. Despite his quick action, the Germans were ready and began hurling grenades toward Johnson and Roberts’s position.

Johnson was severely injured early in the action, but he still was able to hand grenades off to Roberts, who tossed them toward the superior German force. Their efforts did not hold the Germans back though, and the enemy reached their position. Johnson fired three rounds from his rifle before it jammed, and he began using it as a club to fight off the German raiders. In the melee, Roberts suffered a serious wound. The Germans tried to carry him off, but Johnson came to his friend’s aid. Using a knife, Johnson killed two Germans before suffering another bullet wound, but his efforts were successful and the German party fell back. The two Americans became heroes, but not as part of the American Army.

In April 1917 the United States officially declared war on Germany and entered a conflict that had already claimed millions of lives. President Woodrow Wilson used progressive and ideological rhetoric to sell the war to the American populace when he declared “the world must be made safe for democracy.” This proclamation placed the United States at the forefront of an international push to redefine national characteristics and ideals of popular governmental participation.

At home, though, existing prejudices clashed with Progressive Era idealism. Previously marginalized groups hoped the President’s bold claims would carry over to increased enfranchisement, and African Americans believed service in the Great War could translate to wider racial acceptance. The realities of Jim Crow segregation, however, permeated society, including the United States military.

A debate arose over whether the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) would include black soldiers. Ultimately, the War Department created two all-black combat divisions (the 92nd and 93rd Provisional). Most of the men in the 92nd came to military service through the draft, while the 93rd was mostly composed of black National Guard volunteers. As guardsmen, many men in the 93rd represented the citizen-soldier ideal. During this period, the National Guard served as a cross-section of American society, and many men used Guard service as a means of fulfilling a patriotic duty. During the war, the 93rd Division served with distinction, and their operational record demonstrates their fine wartime record.

When the United States entered the Great War, the nation’s military was drastically understrength. Regardless, the War Department hesitated to enlist black soldiers but reluctantly agreed to create a segregated division as part of the new National Army (drafted soldiers). While this move appeased some critics and civil rights activists, black National Guard regiments and companies around the nation remained left out of the nation’s new military composition. Once again, outside pressure forced Secretary of War Newton Baker to allow for the inclusion of black National Guard regiments into the AEF. A memorandum from early 1918, however, notes that when these regiments were consolidated into two brigades, “there was no intention of making a division. But for administrative purposes it has been necessary to designate it as a provisional division, to provide a small staff and to authorize a small amount of transportation for headquarters.”

Though the War Department agreed to create an African American National Guard division, its role in the American Expeditionary Force remained ambiguous. Prior to American entry into the war, the War Department reorganized the Army for overseas combat. They established a series of numbered divisions, with numbers 1 through 25 reserved for Regular Army units, 26 through 75 for the National Guard, and all divisions above 76 for the draftees in the National Army. This organization meant that the National Guard needed to move companies and regiments to fit into the new divisional structure, and following Brig. Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s advice, the War Department created a composite National Guard division composed of regiments and companies from 26 states that were left out of the new structure. The 42nd Division became known as the “Rainbow Division” because, according to Secretary Baker, it “stretched across the nation like a rainbow.” Feeling similarly orphaned by the new breakdown, the all-black 15th New York hoped to join this new division, but its commander was informed that “black was not one of the colors of the rainbow.” Furthermore, while the 93rd was effectively a National Guard division, its high numerical designator actually placed it outside the Guard’s place in the divisional outline.

The 93rd Division began organizing at Camp Stuart, Virginia, in December 1917. The main elements of the division were composed of National Guard units from Connecticut, Washington D.C., Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. The division also included a regiment of drafted soldiers mostly from Tennessee and South Carolina. Unlike every other AEF division though, the 93rd never fully organized, and its four regiments (369th, 370th, 371st, and 372nd) were stationed at training stations in disparate parts of the United States. When the division traveled to France, it did so in piecemeal fashion, with each regiment traveling separately when it reached full strength.

The 15th New York was the first contingent of the 93rd to travel to France. Unlike some of the other Guard regiments in the 93rd Division, the 15th New York was relatively young. Col. William Hayward, a white lawyer originally from Nebraska, organized the regiment into a single element in April 1917. Using his influence, Colonel Hayward and his fellow members of the Union League Club of New York managed to convince the War Department to send the 15th to France in December 1917 (the rest of the 93rd Division would not begin arriving overseas until April 1918). Like the rest of the Guard regiments in the AEF, the Army removed state designators and solidified the National Guard as part of the federal army. Therefore, upon their arrival in France, the 15th New York Infantry became the 369th Infantry. Arriving in Brest, France, in late December, the regiment moved to Saint Nazaire in early January, where it remained until March 13, 1918. During this three-month interlude, the regiment mostly served as a labor force, but its fate (and the division’s) was about to change.

As American troops trickled into France, the AEF commander, Gen.F John J. Pershing, remained locked in a heated debate over amalgamation. The French and British amalgamation plan required the Americans to serve as replacement troops and fall under Allied command. General Pershing refused to accept this idea, as he fully intended to maintain an independent command and serve alongside the French and British, not under them. Pershing believed amalgamation would weaken the American wartime position and alienate the American populace (as well as the troops themselves), who wished to fight for their own interests. Further, if the Americans did not have an independent command, Pershing’s strategic goal of an all-out assault against the German main force by American soldiers would never come to fruition because the Americans would be spread out among European commands. While Pershing’s plans originally included the 93rd Division, the division’s desire to serve in a combat role, combined with existing racial prejudice, prompted the American commander to violate his own stance on amalgamation.

In March 1918, General Pershing ceded control of the 93rd Division to the French Army, and the soldiers remained under French authority for the duration of the war. The French supplied the 93rd Division with arms and equipment, including the blue Adrian helmet, which differed from the broad British helmet the rest of the AEF utilized in the trenches. Over the course of the seven months, the 93rd would aid the French in Gen. Henri Gourand’s “elastic defense strategy,” and two regiments fought under Marshal Ferdinand Foch during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Additionally, the troopers assisted the French during the Oise-Aisne Offensive, just prior to the armistice, where the 370th (formerly the 8th Illinois) regiment earned the French Fourragère, an arm braid given as a unit citation for valor.

Unfortunately, the U.S. Army refused to recognize many of the division’s exploits until many years later because its soldiers did not serve under a unified American command. In May 1918, the U.S. Army considered reassembling the division into the AEF and attached the 93rd’s headquarters personnel to the U.S. 1st and 42nd Divisions. In the end, however, the division never realigned into the AEF.

Less than a month after transferring to the French lines, the 369th moved to the front alongside French troops in the Champagne sector. The regiment served in the Champagne-Marne Defensive for three days between July 15 and 18, 1918, then advanced as part of the Aisne-Marne Offensive between July 18 and 20. In September, the Americans fought with the French during offensive operations along the Champagne front, and on October 14, 1918, the soldiers moved to Alsace as part of the 161st Division, 4th French Army. At this point, the 369th took over sections of the front in the Vosges, where they remained until the end of the war.

While in combat, the 369th earned a reputation as gallant fighters. As noted at the beginning, Needham Roberts and Henry Johnson earned fame in May 1918 when they repulsed a German raiding party despite receiving serious wounds and expending their ammunition. The two men earned the French Croix de Guerre for valor, but the U.S. Army ignored their achievements for decades (Johnson did eventually earn a Distinguished Service Cross, which the Army upgraded posthumously to the Medal of Honor in 2015). The press, however, spread their story in both France and the United States. Johnson earned the nickname “Black Death,” and the 369th collectively earned the moniker “Harlem Hell Fighters.” After 191 days in action, the New Yorkers served as the advance guard for the 161st French Division, and one week after the armistice, the Harlem Hell Fighters became the first Allied regiment to reach the Rhine River, on the border of France and Germany near Blodelsheim.

Meanwhile, just as the 369th was moving toward the front lines, guardsmen from the old 8th Illinois began arriving in France. Newly designated as the 370th Infantry, they traveled overseas in April 1918 and began training with various French divisions until the end of August. Much of this training, as for other combat divisions, consisted of holding defensive positions along the lines. On September 15, the regiment—as part of the 59th Division, French Army—went into line northeast of Soissons, where it participated in the Oise-Aisne Offensive until October 12. The Illinoisans resumed offensive operations on October 24 and continued until the end of the war. The regiment departed Brest, France, on February 1, 1919, and arrived in New York eight days later.

When the 370th joined the Oise-Aisne Offensive, four American rifle companies joined two French regiments and charged the German lines. After intense fighting, the combined force captured their objectives. In their first major offensive operation, the Illinois guardsmen served admirably. On September 27, elements of the 370th moved in to relieve a French battalion on the front lines. Orders came down for the regiment to attack L’Ecluse at dawn. Over the next three days, the regiment regularly engaged the enemy. As with many fresh troops, confusion set in during the fighting—particularly during the darkness of night. Ultimately, many men became separated from their units during operations, and rumors began to spread that the regiment was becoming demoralized. In reality, the soldiers pressed on during the offensive, and despite units getting mixed, within a few days all men were accounted for. Sporadic attacks continued into October, but by the fourth, the Germans had retreated across the canal. One week later, the French ordered a general advance in pursuit of the German forces. For their actions during the advance, the French commander commended two of the 370th’s battalions (the 1st and 2nd) for their actions in the face of the enemy.

The third regiment of the 93rd also began arriving in France in April 1918 and served as an independent unit of the 13th French Army Corps. Unlike the other three regiments in the 93rd Division, the 371st Infantry was a National Army regiment and was composed mostly of conscripted soldiers from South Carolina. The regiment remained in the vicinity of Bar-le-Duc until June, when it joined the 68th Division of the French Army near Verdun. On September 27, the regiment participated in offensive operations along the Champagne front with the 157th Division, 9th French Army Corps. The next day, Company C led an attack on Hill 188. Shortly after the charge began, the Germans began climbing out of the trenches with their arms up as if they were surrendering. It was a ruse, however. When the Americans ceased fire and moved into the open, the Germans jumped back into their trench and opened fire. Cpl. Freddie Stowers took charge and crawled toward one of the German machine gun nests ahead of his squad. After his squad took the position, Corporal Stowers continued onward, but he was mortally wounded by machine-gun fire. His company followed his lead and pressed on until they took the hill and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy. Though the U.S. Army initially ignored Stowers’s bravery, he eventually earned the Distinguished Service Cross, and in 1991 the Army upgraded this to its highest honor, the Medal of Honor.

Two weeks after this action, the French withdrew the 157th Division (including the 371st) from the front, and it traveled to the Alsace sector, where it remained until the end of hostilities. French Gen. Mariano F.J. Goybet, commander of the 157th Division, recommended an Order of the Army citation for the 371st Regiment for their actions in taking a position “after a fiece [sic] fighting under an exceptionally violent machine gun firing.” Like the other regiments in the 93rd Division, the 371st left for home in early February 1919. As the 371st prepared to return to American command in December, one French colonel of the 157th Division thanked his American comrades by saying, “After having energetically held trenches in difficult sectors, they have taken a glorious part in the great and decisive battle, which has given us the final victory. They have shown, in sector, a remarkable spirit of strength, vigilance, devotion and discipline. In the battle they have taken gallantly, and with magnificent bravery, very strong positions strongly defended by the enemy.” The colonel went on to say that he would always keep in his heart the “faithful memory” of the American regiments as well as Col. Perry Miles and Col. Hershel Tupes, who “are now my good friends.”

The 372nd Infantry, which was the fourth regiment in the 93rd Division, comprised guardsmen from various states and the District of Columbia. From the end of April 1918 until early June, the regiment trained with the French Army in the vicinity of Givry-en-Argonne. Over the next three months, the regiment remained mostly in the Argonne sector, but in September they moved to the Champagne front, where they joined other regiments from the 93rd Division who were advancing with the 4th French Army. From that point onward, the 372nd served with its counterparts in the 371st Regiment, and on October 13, 1918, it took up a position in the Alsace sector. In early December, the 371st and 372nd returned to American command. As a show of respect for the Americans, General Goybet offered words of praise and proclaimed that “for seven months we have lived as brothers in arms, sharing the same burdens, the same hardships, the same dangers.” He went on to say that “the 157th D.I. will never forget the irresistible, heroic rush of the Colored American Regiments up the ‘Creto des Observatoires’ and into the ‘Plaine de Monthois.’ The most formidable defenses, the strongest machine gun nests, the most crushing artillery barrages were unable to stop them.” The 372nd arrived back in the United States on February 12, 1919.

Throughout the war, relations between the French troops and the Americans in the 93rd Provisional Division remained fairly cordial. According to one memorandum from the commanding officer of the 370th though, “there was not always a degree of cooperation that was desirable in order to remove the difficulties due to lack of complete comprehension and difference in methods.” The memorandum went on to point out that the French did not treat the Americans unfairly. Not surprisingly, much of the confusion between the combined units related to the language barrier. All orders needed to be translated and redistributed to lower echelons, but a shortage of competent interpreters slowed this process. Language hurdles could sometimes create severe problems. For example, “a liaison agent that did not know his route perfectly was invariably lost for several days; names that appeared on maps were not recognized when spoken; transport was usually lost during movement and during the night supply of the lines—these were only a part of the difficulties arising from the difference in language.” These problems hindered efficiency in the 93rd Division, but as operations progressed, the Americans’ combat abilities improved.

When the fighting ceased on November 11, 1918, the 369th became an occupation force along with the rest of the AEF. However, just as during the war, elements of the division served with the French Army. The 369th became part of the French Army of Occupation, where it remained until December 8, 1918, when the French Army relieved it from duty. The New Yorkers then traveled to the Le Mans Embarkation Center, where they prepared to return to the United States. The regiment sailed from Brest on February 2, 1919, and arrived back in New York 10 days later. In the months between the armistice and their return home, the 93rd Division suffered from a series of sociopolitical defeats. The Wilson administration and commanders denied black soldiers the right to march in U.S. victory parades in France and denied the entire 93rd Division recognition of their military exploits. Additionally, the U.S. Army disregarded the 93rd’s contributions to the war effort because it recorded that “the 93rd Division spent zero days in training in line, zero days in sector, and zero days in battle,” despite the fact that the division suffered over 520 soldiers killed and more than 2,600 wounded throughout 1918. Indeed, the division’s combat record served as a testament to the National Guard’s abilities but reflected racial sentiments that plagued the nation during the early 20th century.

When the 93rd Division returned to the United States, its men returned to their homes. Although the AEF denied them recognition of their exploits while in France, American cities generally welcomed their soldiers with open arms. In February 1919, the Harlem Hell Fighters of the 369th proudly marched down Fifth Avenue in New York City with their French awards prominently displayed on their uniforms. With the American colors waving at the head of the column, New York’s most prominent citizens came out to honor the troops, including New York Governor Al Smith and former Governor Charles Whitman. Rodman Wanamaker and Maj. Gen. Thomas H. Barry also stood in the reviewing stand alongside acting New York Mayor Robert Moran.

Though New York welcomed these soldiers with a grand spectacle, the years following the end of the First World War proved difficult for many African Americans. Despite high hopes, the war failed to secure a stronger position for black citizens, particularly in the American south, where segregation continued uninterrupted. Eventually the U.S. Army recognized the 93rd Division’s exploits, but even this took another decade.

The First World War did not usher in a better reality for most African American citizens, but the men who served in combat did so with distinction. The operational records of the segregated black combat divisions prove this point. For the men of the mostly National Guard 93rd Division, these soldiers also carried a local sense of pride as citizen-soldiers who represented not only their nation but their home states as well. New York soldiers of the old 15th regiment were the first to arrive in France and found themselves serving not with the AEF but with the French Army. As the rest of the 93rd traveled to France, they too served in the French lines. Despite this segregation, the division fought with tenacity and earned the respect and honors of their French peers. Eventually the United States Army also recognized their service, and men such as Henry Johnson earned high praise. Indeed, the 93rd Division’s combat record proves that these soldiers served their country well.

Matthew Margis is a historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History and a former archives technician in the Still Picture Branch at the National Archives and Records Administration. He earned his Ph.D. in history from Iowa State University in 2016.

Note on Sources

Historians have examined the experiences of black soldiers during and after the First World War in a variety of ways. Arthur W. Little’s 1936 book, From Harlem to the Rhine: The Story of New York’s Colored Volunteers, discussed the 15th New York’s activities during the First World War. More recently, Frank E. Roberts’s 2004 book, The American Foreign Legion: Black Soldiers of the 93rd in World War, focused on the 93rd Division’s experiences throughout the war. However, until 2010, Arthur E. Barbeau and Florette Henri’s 1974 work The Unknown Soldiers: African-American Troops in World War I was the only comprehensive study of black soldiers in the Great War. Chad Williams reexamined the role black soldiers played during the First World War in Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. Williams’s work stressed elements of racial prejudice and military prowess among black soldiers during and after the war. Specifically regarding the National Guard, Charles Johnson’s African American Soldiers in the National Guard, offers a compelling narrative of black troops in the old militia and in segregated Guard units through the Guard’s eventual integration in 1950. Johnson discussed the ways in which the militia and National Guard appealed to black Americans’ conceptions of virtue and civil service.

Eleanor Hannah’s 2007 work, Manhood, Citizenship, and the National Guard: Illinois 1870–1917, also discussed patriotic ideals and civic virtue. Regarding black soldiers, Hannah points out that many African Americans used Guard service as a way of demonstrating their loyalty and attaining a sense of citizenship. Each of these historical studies utilized records in the holdings at the National Archives, and while they each tell an important part of these soldiers’ overall experiences, they avoid operational discussions. David Kennedy’s seminal work, Over Here: The First World War and American Society, examines the social and cultural trends of the era.

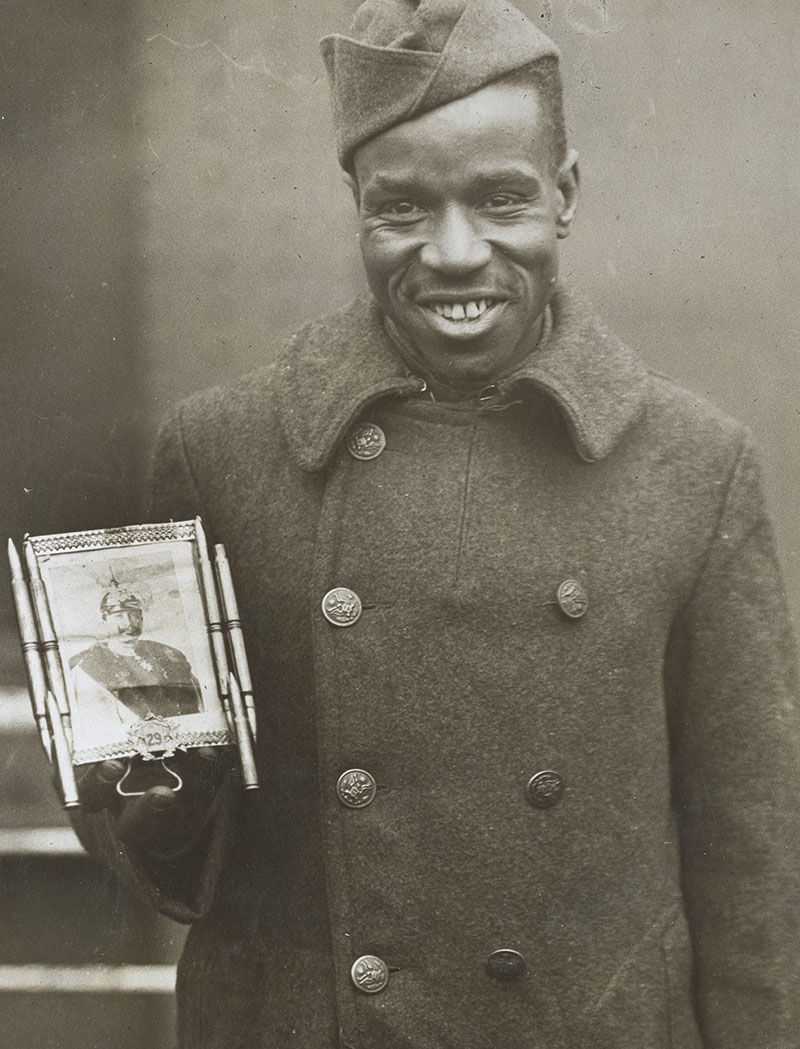

When studying the military operations of the 93rd Provisional Division (and the other divisions in the AEF), interested parties will find value in the records contained in Record Group 120 in the National Archives at College Park. The majority of this article is based on the historical reports, memoranda, daily reports, and action reviews contained therein. While these textual records provide valuable insights into the daily activities of these troops, other collections help add nuance to this complex story. Photographic records in Record Groups 165-WW and 111-SC offer a visual component to these soldiers’ wartime experiences, and the captions on these images provide context into existing ideologies and prejudices.