Episodes 5-8

Episode 5: America Goes to War

Johnson orders air campaign and sends first ground troops to Vietnam

We will fight whatever way the United States wants.

After winning the Presidential election in a landslide, President Johnson was faced with a deteriorating situation in Vietnam. Pressured by advisers predicting “disastrous defeat,” intent on proving his and America’s “credibility,” fearful of drawing China and the Soviet Union into the conflict, and passionate about maintaining focus on his “Great Society” initiative, he planned a course of gradual escalation he hoped would avoid public scrutiny.

In January 1965, after southern Communist forces attacked a U.S. air base, the administration had a pretext to launch Operation Rolling Thunder, a sustained bombing campaign against the north. An air campaign necessitated an air base, and an air base needed protection, so the first American boots hit the ground soon after the bombing began. Hundreds of thousands of U.S. combat troops would follow. America was at war.

See Documents and Photos from Episode 5

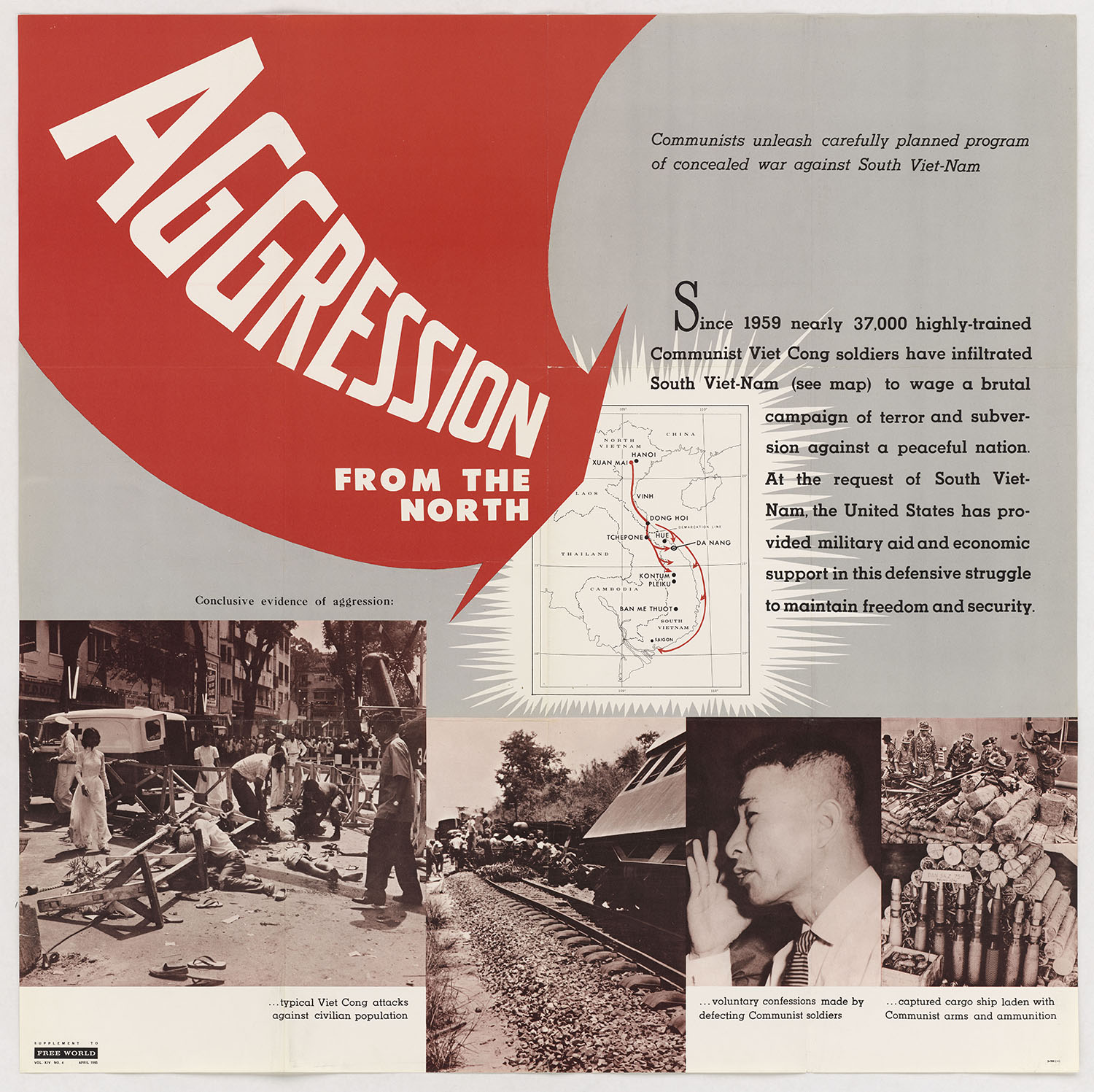

“Aggression from the North” United States Information Agency poster, 1965

A 1965 policy paper titled “Aggression from the North” portrayed the war as an invasion by the North Vietnamese with Moscow pulling the strings.

National Archives, Records of the U.S. Information Agency View In the Online Catalog

Watch the Interviews from Episode 5

Key Dates

February 7, 1965: National Liberation Front attack on Pleiku Air Base

March 2, 1965: Operation Rolling Thunder

March 8, 1965: 3,500 Marines arrive at Danang Harbor

March 21, 1965: Selma to Montgomery Civil Rights March

May 21, 1965: Large teach-in at the University of California at Berkeley

August 6, 1965: Johnson signs Voting Rights Act

November 14, 1965: Battle of la Drang begins

November 27, 1965: Tens of thousands march on Washington against the Vietnam War

December, 1965: American forces reach 175,000

Episode 6: Fighting on Three Fronts

Tension between military strategy, humanitarian efforts, and antiwar activism reach crisis levels

If America's soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read “Vietnam.”

The American strategy in Vietnam was to suppress the Communist insurgency through the ground war while winning the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese through humanitarian efforts. But it was difficult to build bonds with people whose lives were upended by the search-and-destroy tactics of the combat forces.

Back at home, antiwar protests mounted. Public support for the war fell below 50 percent for the first time. In October 1967, nearly 100,000 people joined the March on the Pentagon to protest the war. The Johnson administration tried to tamp down dissent with news of progress, going so far as to call General Westmoreland home from the battlefield to present a glowing report to the American people. Military officers were pressured to overestimate enemy casualties and underestimate enemy strength—a practice that would have devastating consequences for President Johnson.

The “War at Home”

Opposition to the war grew, diversified, and clashed with supporters in a more and more divided nation

For the first time in history, the death and destruction of war was beamed onto television screens in living rooms around the world. This portal into the grim realities of war turned more and more people against it. But many Americans, even some who opposed the war, felt protest marchers were disloyal to American soldiers, further dividing the population in the growing “War at Home.”

As troop levels neared half a million, casualties mounted with no apparent progress, and tens of thousands of young men—disproportionately blue collar and minority—were drafted each month, opposition to the war mounted. Some peace-promoting doves saw the war as a well-intentioned but disastrous mistake. War-minded Hawks blamed the media for turning the population against a winnable war. The bitter polarization of American society begun during the Vietnam War is still evident today.

See Documents and Photos from Episode 6

Portrait of Russell Forrest Keck, undated

Corporal Russell Forrest Keck died in Vietnam on May 18, 1967. He was 20 years old.

National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum

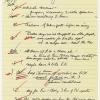

President Johnson’s draft response to Mr. and Mrs. Keck, June 14, 1967

In long letters to President Johnson, Russell Keck’s parents expressed their anger and grief at losing their son. His draft reply, with its layers of revised and rejected phrases, reveals his struggle to respond.

National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum

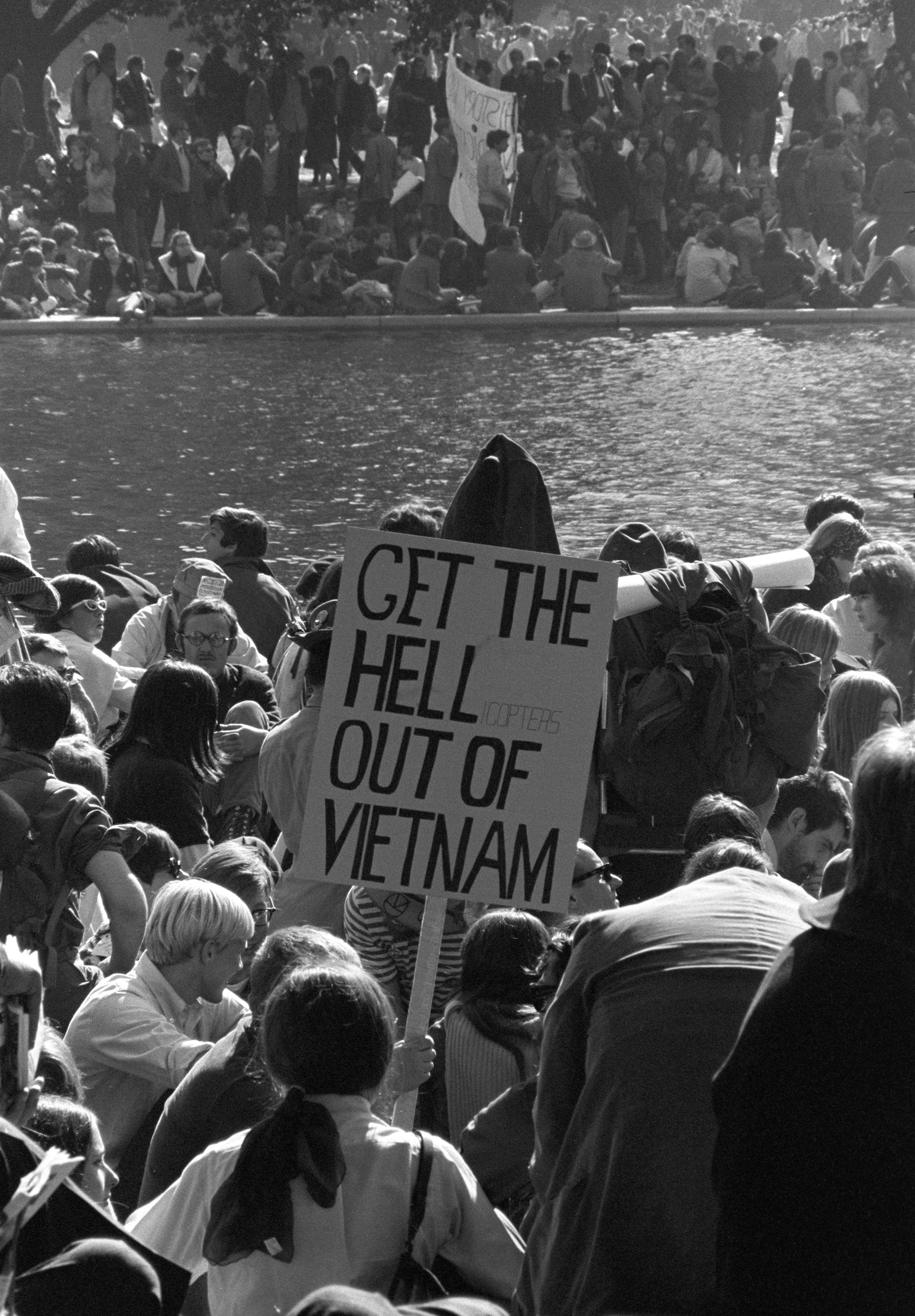

Protesters at March on the Pentagon, October 21, 1967

In October of 1967, 70,000 protesters marched on the Pentagon, the headquarters of the Department of Defense, to protest the war in Vietnam.

National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum View in the Catalog

Watch the Interviews from Episode 6

Key Dates

April 4, 1967: Martin Luther King Jr. denounces Vietnam War

April 28, 1967: Boxer Muhammad Ali refuses military service

July 1967: Clashes between black residents and police in Detroit and Milwaukee

August 1967: Race conflict in Washington, DC

October 1967: Protests at the University of California at Berkeley and the Lincoln Memorial

October 26, 1967: Navy pilot John McCain shot down over North Vietnam and taken prisoner

November 3–22, 1967: Battle of Dak To

December 1967: Troop level reaches 485,600

Episode 7: Tet Offensive

Americans lose faith in the potential for victory after wide-ranging Communist attacks

It seems now more certain than ever, that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate.

On January 31, 1968, the South Vietnamese were looking forward to Tet, a celebration of the lunar new year. They were caught off guard when 70,000 Communist troops struck more than 100 towns and cities with swift and stunning ferocity.

Most of the fighting was over in a few days, but a second wave came in late April and a third in August. Although the enemy suffered devastating casualties and their attempt to spark a general uprising completely failed, many Americans concluded the U.S. and its allies had suffered a massive defeat. When a Defense Department report regarding the need for 205,000 more American troops was leaked to the New York Times, Americans concluded the war was stalemated and the Johnson administration had lied to them.

See Documents and Photos from Episode 7

Reading copy of Westmoreland’s Press Club address, 1967

President Johnson brought the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, General William Westmoreland, stateside to project optimism about the war at the end of 1967.

National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum

Memorandum from Walt W. Rostow to President Johnson, January 30, 1968

Special Assistant for National Security Affairs Walt Rostow notified President Johnson of the breach of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon during the Tet Offensive.

National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum

“Navy Hospital Corpsman D. R. Howe treats the wounds of Private First Class D A. Crum, ‘H’ Company 2nd Battalion, Fifth Marine Regiment during Operation Hue City, February 6, 1968.”

National Archives, Records of the United States Marine Corps View in the Online Catalog

Watch the Interviews from Episode 7

Key Dates

January 21, 1968: Battle of Khe Sanh begins

February 27, 1968: Anchorman Walter Cronkite concludes the United States “is mired in a stalemate”

March 16, 1968: My Lai Massacre

March 31, 1968: Johnson announces he will not seek reelection

April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King Jr. is assassinated

May 10, 1968: Paris Peace Talks begin

June 6, 1968: Robert Kennedy is assassinated

October 31, 1968: Johnson orders halt to bombing on North Vietnam

Episode 8: Nixon’s Campaign Promise

Nixon scuttles Johnson’s peace talks before the election and expands the war after it

Nixon’s Presidential campaign led many to conclude he had a “secret plan to end the war.” Some historians believe he was actually determined to win the war. Others say he planned a negotiated withdrawal from the beginning. We do know he had a secret. He sabotaged Johnson’s peace talks to try to prevent an agreement from threatening his election.

As President, Nixon escalated the bombing and expanded the war in Cambodia and Laos. After millions demonstrated in the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, he announced his plan for “Vietnamization” and asked “the great silent majority” of Americans for their support. The war continued for four years under Nixon. During that time, 21,041 Americans and over two million Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians were killed.

See Documents and Photos from Episode 8

Haldeman’s notes, October 22, 1968

On the night of October 22, 1968, according to the notes of H. R. Haldeman, Richard Nixon’s closest aide, Nixon told him to tell John Mitchell to “keep Anna Chennault working on SVN” and to ask Bryce Harlow if there was “Any other way to monkey wrench” LBJ’s efforts to enter peace talks with both Vietnam regimes.

National Archives, Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum View in the Online Catalog

Cable from Rostow to Johnson, November 2, 1968

This cable states that on November 2, three days before the election, Nixon campaign associate Anna Chennault contacted the South Vietnamese Ambassador to encourage Saigon to refuse to participate in LBJ’s peace efforts.

National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum

President Richard Nixon and First Lady Pat Nixon wave from the Presidential limousine in the inaugural motorcade, January 20, 1969

National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum View in the Online Catalog

Watch the Interviews from Episode 8

Key Dates

January 20, 1969: Nixon’s inauguration

March 18, 1969: Nixon begins secret bombing of Cambodia

April, 1969: Number of American military personnel in Vietnam peaks at 543,000

June 8, 1969: Announcement of 25,000 troop withdrawal

July 20, 1969: Neil Armstrong walks on the Moon

September 2, 1969: Ho Chi Minh dies of a heart attack

October 15, 1969: National Moratorium to End the War

November 3, 1969: Vietnamization & Silent Majority speech

November 15, 1969: Over 500,000 join Moratorium March on Washington