Executive Order 10924: Establishment of the Peace Corps. (1961)

On March 1, 1961, President Kennedy signed this executive order establishing the Peace Corps. On September 22, 1961, Congress approved the legislation that formally authorized the Peace Corps. Goals of the Peace Corps included: 1) helping the people of interested countries and areas meet their needs for trained workers; 2) helping promote a better understanding of Americans in countries where volunteers served; and 3) helping promote a better understanding of peoples of other nations on the part of Americans.

The founding of the Peace Corps is one of President John F. Kennedy's most enduring legacies. Yet it began in a fortuitous and unexpected moment. Kennedy, arriving late to speak to students at the University of Michigan on October 14, 1960, found himself thronged by a crowd of 10,000 students at 2 o'clock in the morning. Speaking extemporaneously, the Presidential candidate challenged American youth to devote a part of their lives to living and working in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Would students back his effort to form a Peace Corps? Their response was immediate: Within weeks, students organized a petition drive and gathered 1,000 signatures in support of the idea. Several hundred others pledged to serve. Enthusiastic letters poured into Democratic headquarters. This response was crucial to Kennedy's decision to make the founding of a Peace Corps a priority. Since then, hundreds of thousands of citizens of all ages and backgrounds have worked in more than 140 countries throughout the world as volunteers in such fields as health, teaching, agriculture, urban planning, skilled trades, forestry, sanitation, and technology.

By 1960, two bills were introduced in Congress that were the direct forerunners of the Peace Corps. Representative Henry S. Reuss of Wisconsin proposed that the federal government study the idea, and Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota asked for the establishment of a Peace Corps itself. These bills were not likely to pass Congress at the time, but they caught the attention of then-Senator Kennedy for several important reasons. In contrast to previous administrations, Kennedy foresaw a "New Frontier" inspired by Roosevelt's New Deal. The New Frontier envisioned programs to fight poverty, help cities, and expand governmental benefits to a wide array of Americans.

In foreign affairs, Kennedy was also more of an activist than his predecessor. He viewed the Presidency as "the vital center of action in our whole scheme of government." Concerned by what was then perceived to be the global threat of communism, Kennedy looked for creative as well as military solutions. He was eager to revitalize a program of economic aid and to counter negative images of the "Ugly American" and Yankee imperialism. He believed that sending idealistic Americans abroad to work at the grass-roots level would spread American goodwill into developing nations and help stem the growth of communism there.

Kennedy lost no time in actualizing his dream for a Peace Corps. Between his election and inauguration, he ordered Sargent Shriver, his brother-in-law, to do a feasibility study. Shriver remembered, "We received more letters from people offering to work in or to volunteer for the Peace Corps, which did not then exist, than for all other existing agencies."

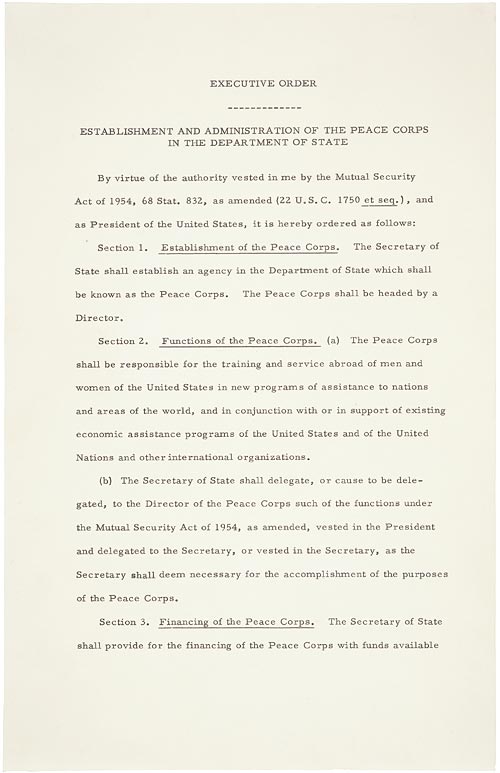

Within two months of taking office, Kennedy issued an executive order establishing the Peace Corps within the State Department, using funds from mutual security appropriations. Shriver, as head of the new agency, assured its success by his fervent idealism and his willingness to improvise and take action.

To have permanency and eventual autonomy, though, the Peace Corps would have to be approved and funded by Congress. In September 1961, the 87th Congress passed Public Law 87-293 establishing a Peace Corps. By this time, because of Kennedy’s executive order and Shriver's leadership, Peace Corps volunteers were already in the field.