Archives Recalls Fire That Claimed Millions of Military Personnel Files

By Kerri Lawrence | National Archives News

WASHINGTON, July 23, 2018 — The National Archives and Records Administration recently marked the 45th anniversary of a devastating fire at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in St. Louis, Missouri, that destroyed approximately 16–18 million Official Military Personnel Files (OMPF) documenting the service history of former military personnel discharged from 1912 to 1964.

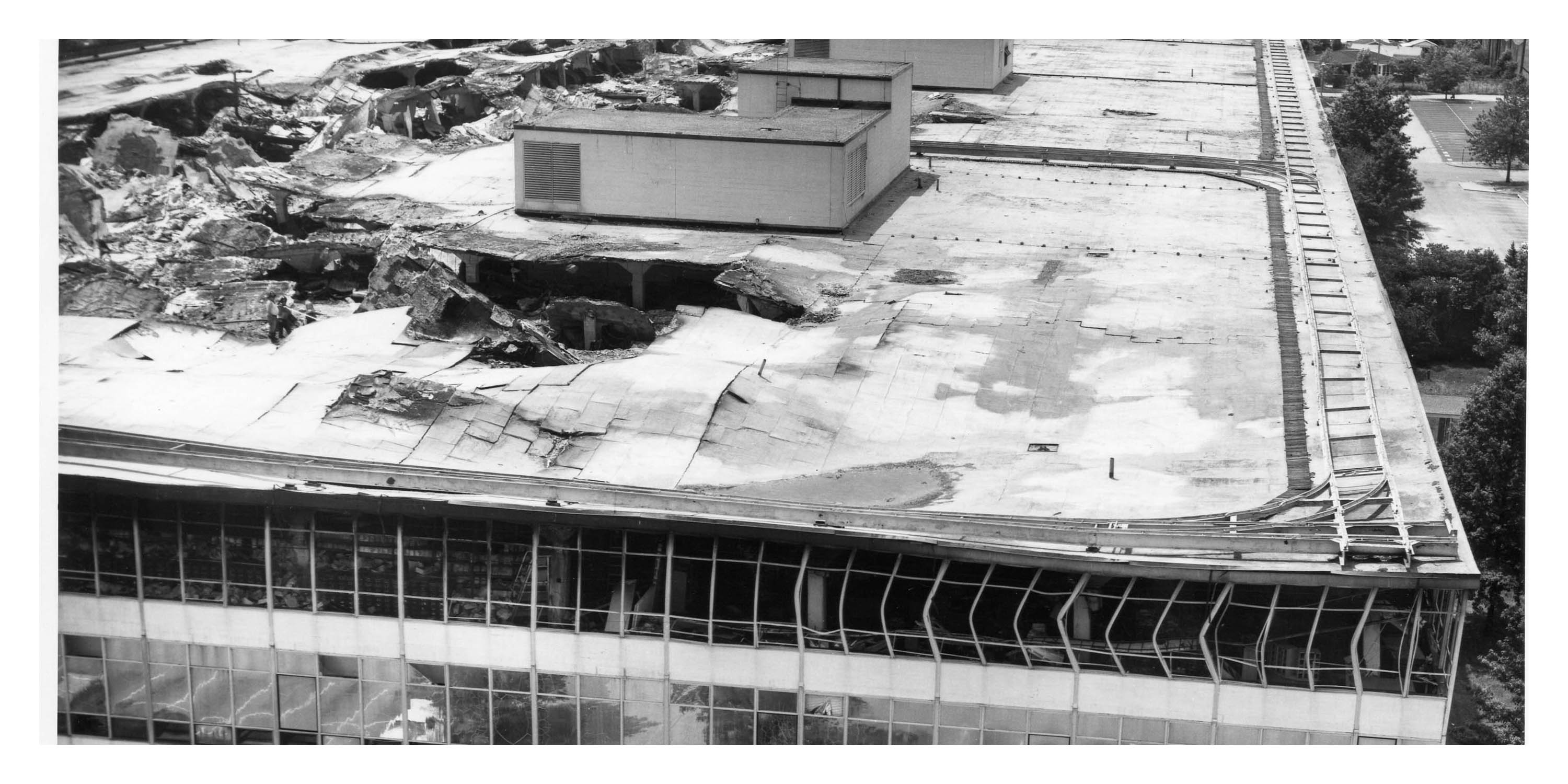

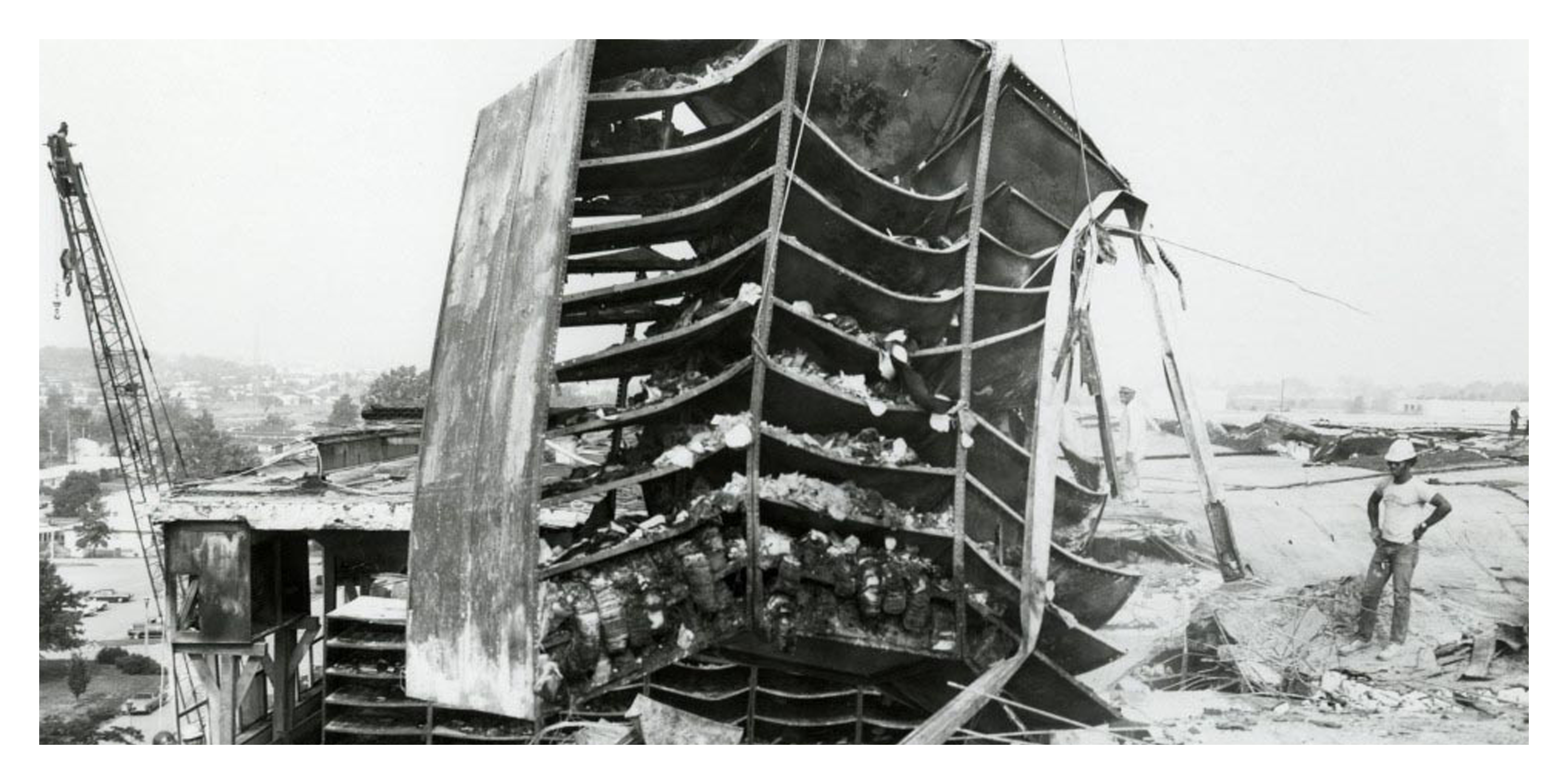

Shortly after midnight on July 12, 1973, a fire was reported at the NPRC's military personnel records building in St. Louis, Missouri. The fire burned out of control for 22 hours and it took two days before firefighters were able to re-enter the building. Due to the extensive damage, investigators were never able to determine the source of the fire.

The National Archives focused its immediate attention on salvaging as much as possible and quickly resuming operations at the facility. Even before the final flames were out, staff at the NPRC had begun work toward these efforts as vital records were removed from the burning building for safekeeping.

“In terms of loss to the cultural heritage of our nation, the 1973 NPRC fire was an unparalleled disaster,” Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero said. “In the aftermath of the blaze, recovery and reconstruction efforts took place at an unprecedented level. Thanks to such recovery efforts and the use of alternate sources to reconstruct files, today's NPRC is able to continue its primary mission of serving our country's military and civil servants.”

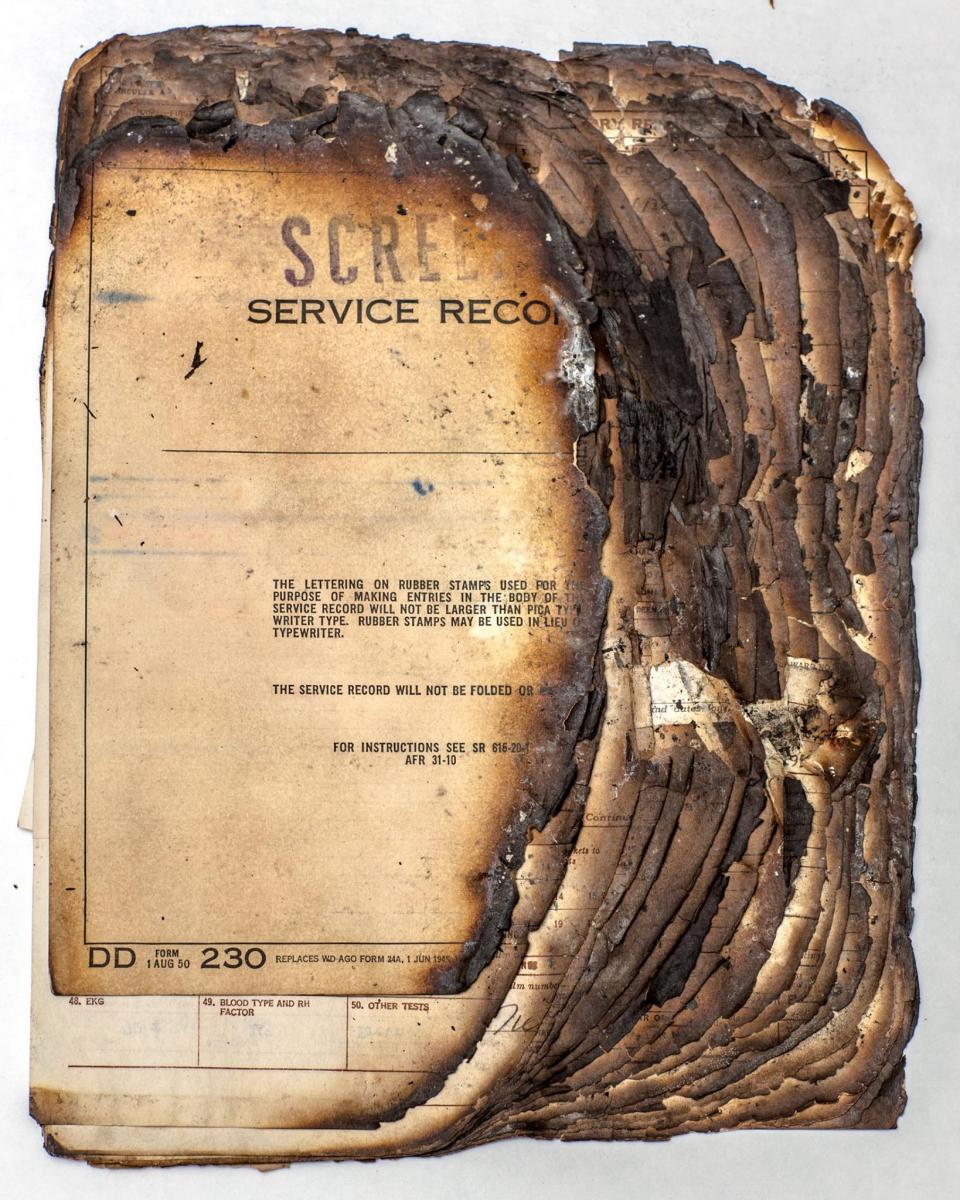

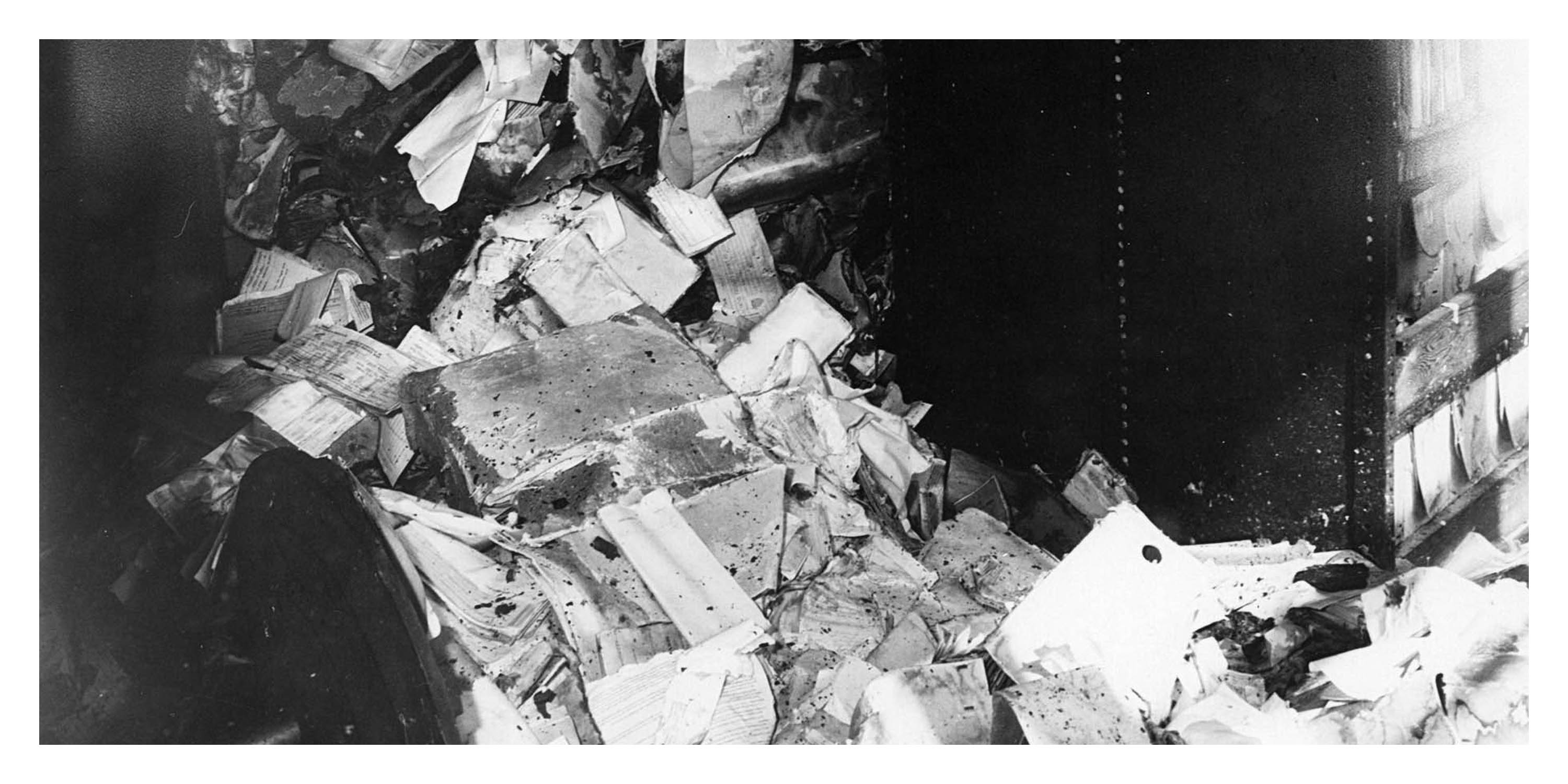

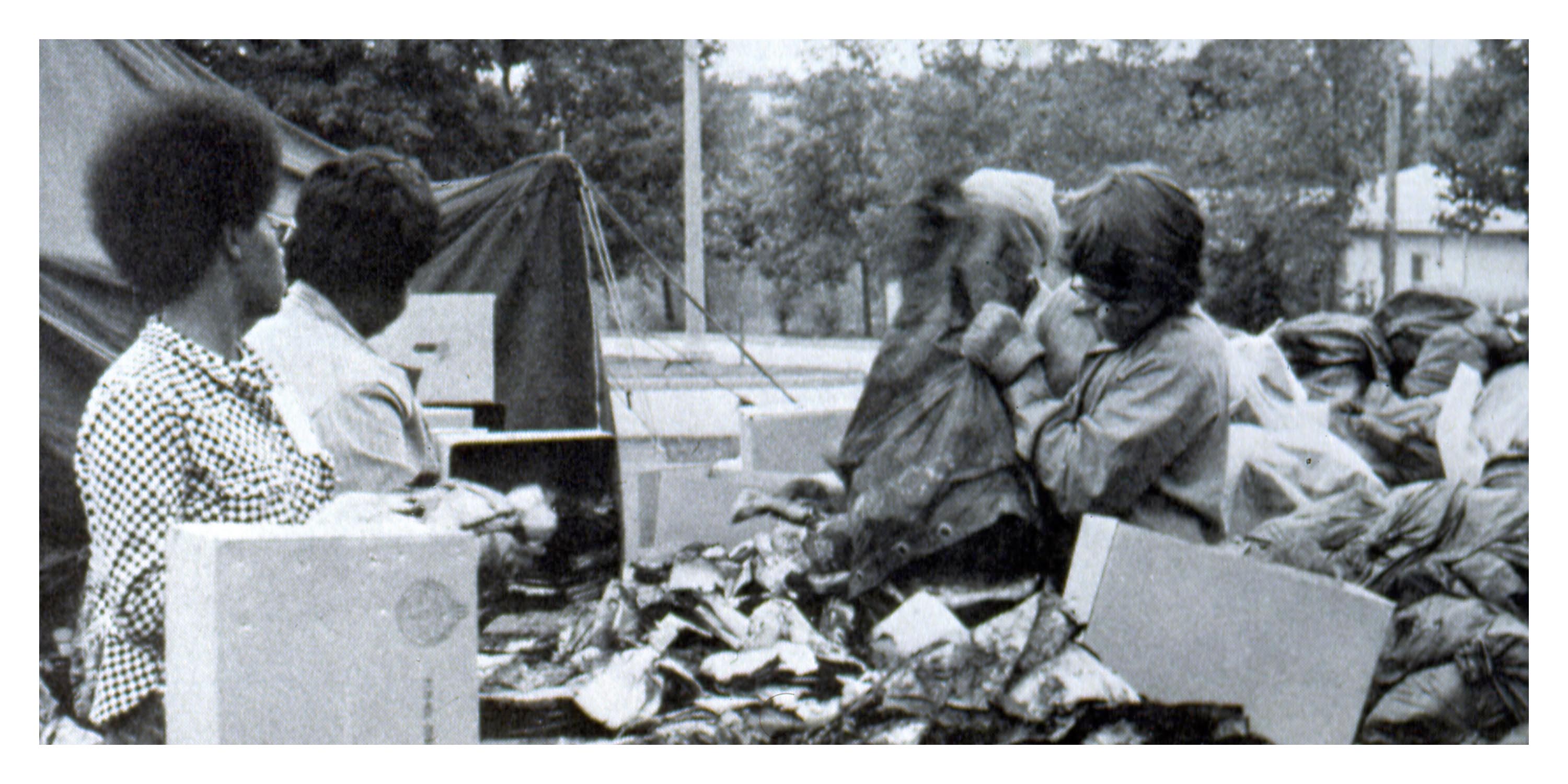

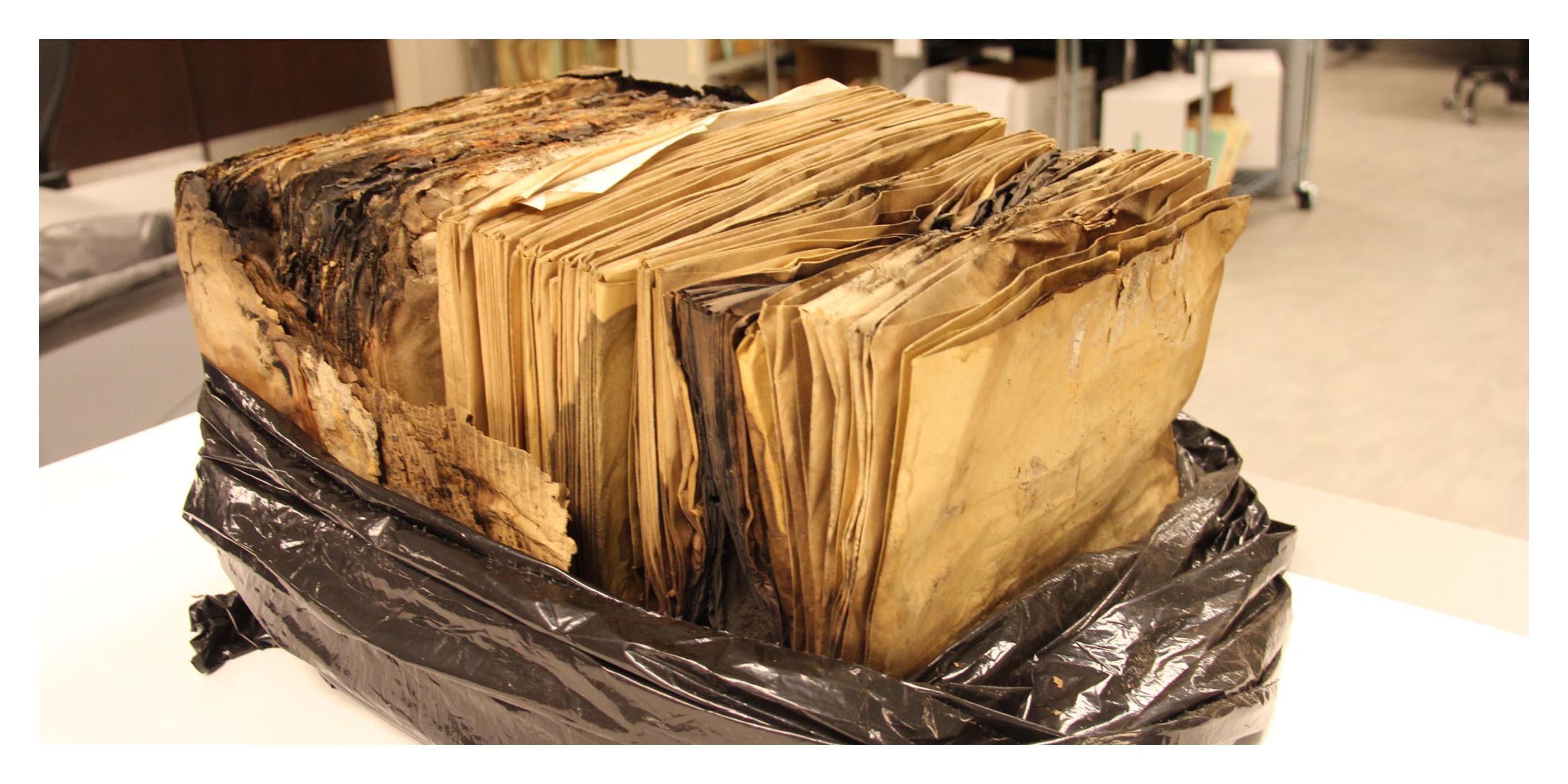

Removal and salvage of water- and fire-damaged records from the building was the most important priority, according to NPRC Director Scott Levins. Standing water—combined with the high temperatures and humidity—created a situation ripe for mold growth. This work led to the recovery of approximately 6.5 million burned and water-damaged records, Levins said.

The estimated loss of Army personnel records for those discharged from November 1, 1912, to January 1, 1950, was about 80 percent. In addition, approximately 75 percent of Air Force personnel records for those discharged from September 25, 1947, through January 1, 1964 (with names alphabetically after Hubbard, James E.) were also destroyed in the catastrophe.

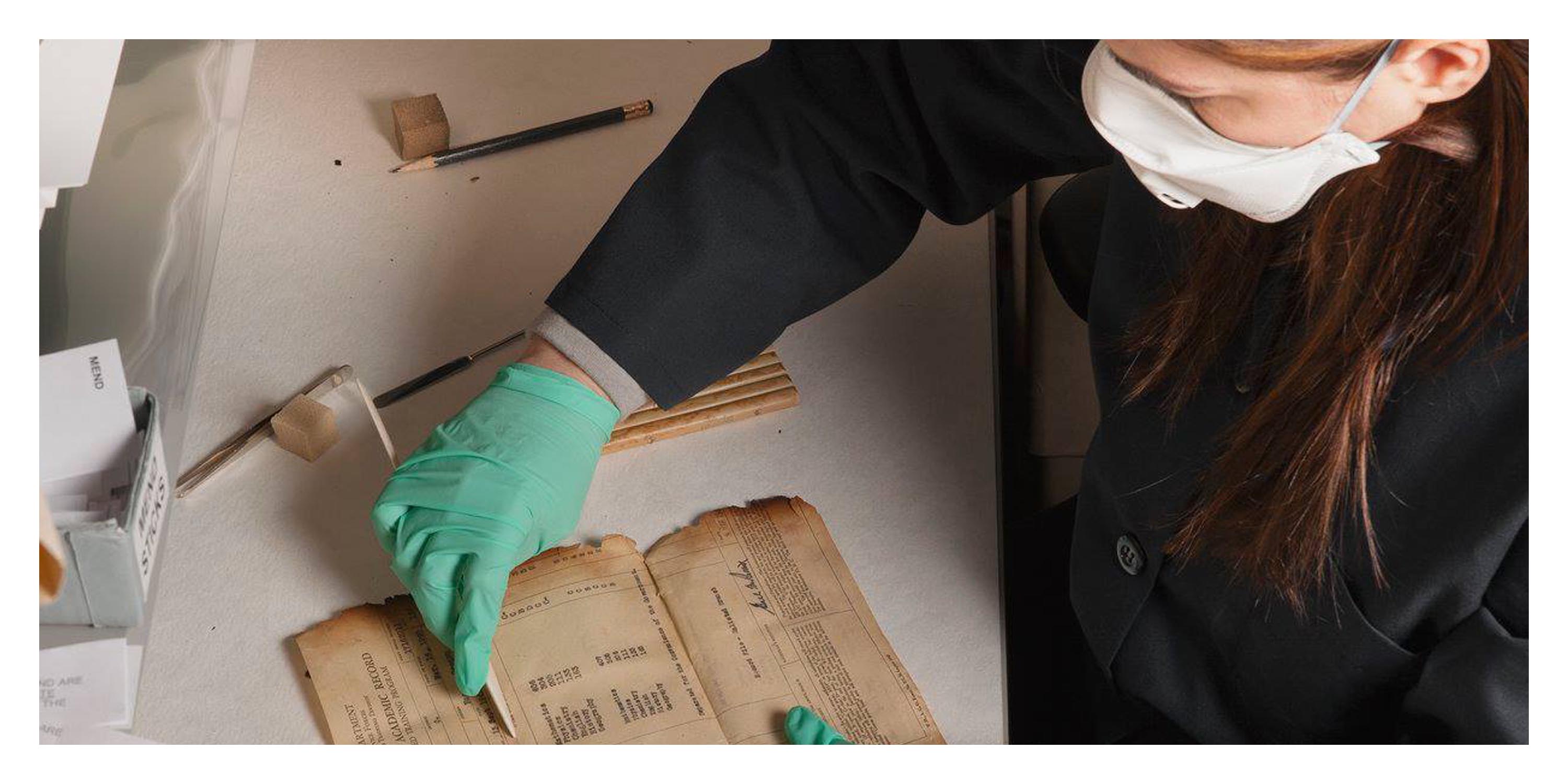

However, in the years following the fire, the NPRC collected numerous series of records (referred to as Auxiliary Records) that are used to reconstruct basic service information.

Bryan McGraw, access coordinator at the NPRC, emphasized the gravity of the loss of the actual primary source records. “Unfortunately, the loss of 16–18 million individual records has had a significant impact on the lives of not only those veterans, but also on their families and dependents,” McGraw said. “We can usually prove eligibility for benefits and get the vet or next of kin their entitlements; however, we cannot recreate the individual file to what it was—we don't know what was specifically in each file, and each of these was as different as each of us as individuals. So from a purely historic or genealogical perspective, that material was lost forever.”

In the days following the fire, recovery teams faced the issue of how to salvage fire-damaged records as well as how to dry the millions of water-soaked records. Initially, NPRC staffers shipped these water-damaged records in plastic milk crates to a temporary facility at the civilian records center where hastily constructed drying racks had been assembled from spare shelving. When it was discovered that McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Corporation in St. Louis had vacuum-drying facilities, the NPRC diverted its water-damaged records there for treatment using a vacuum-dry process in a chamber large enough to accommodate approximately 2,000 plastic milk cartons of water- and fire-damaged records.

"This is a somber anniversary,” Levins said. “In terms of the number of records lost and lives impacted, you could not find a greater records disaster. Although it's now been 45 years since the fire, we still expend the equivalent of more than 40 full-time personnel each year who work exclusively on responding to requests involving records lost in the fire."

Much has been written about the fire and its aftermath. A white paper, The National Personnel Records Center Fire: A Study in Disaster, provides an extensive account. It was originally published in October of 1974 in The American Archivist, Vol. 37, No. 4. In addition, Prologue magazine published "Burnt in Memory: Looking back, looking forward at the 1973 St. Louis Fire."

Each year, the NPRC connects more than a million veterans with their OMPFs as part of the National Archives’ services to the nation.