Bisa Butler Quilts Harlem Hellfighters into History

By Victoria Macchi | National Archives News

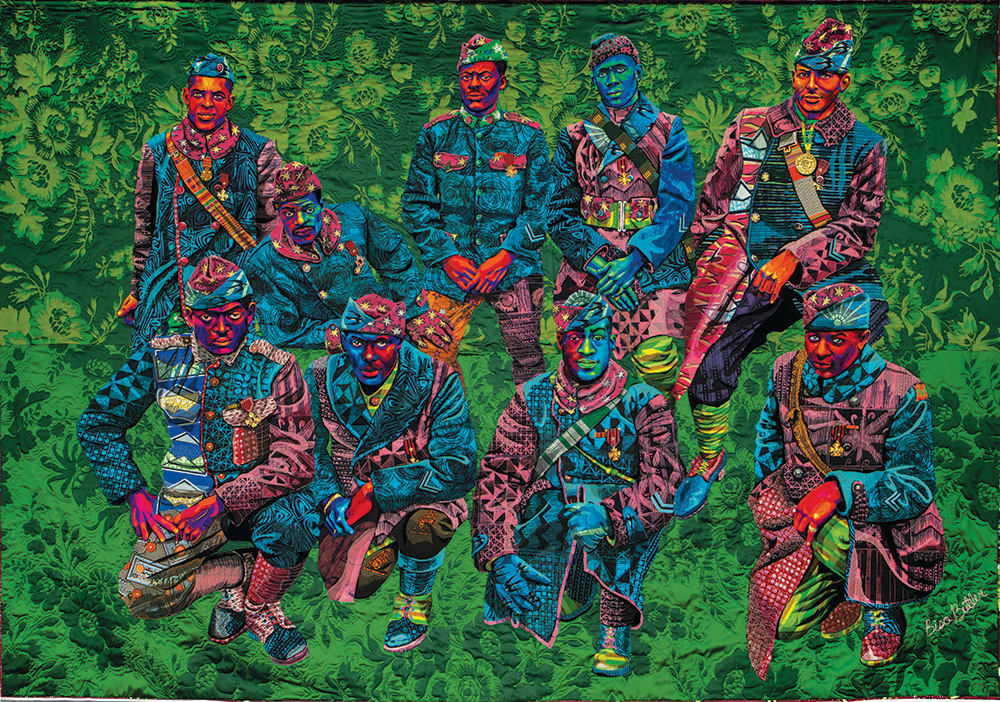

WASHINGTON, March 1, 2023 — Artwork inspired by a World War I–era photo of Black soldiers known as the Harlem Hellfighters turns a National Archives record into a larger-than-life quilt at the Renwick Gallery in Washington, DC.

Bisa Butler crafted "Don’t Tread on Me, God Damn, Let’s Go! — The Harlem Hellfighters" after finding the image during online research.

“It was one of the thrills of my life to be able to study and create artwork based off of the National Archives’ magnificent photo,” Butler said of the image, taken by the International Film Service.

“I’m used to seeing beautiful photos of the Tuskegee Airmen, so I assumed I was looking at them,” the artist told National Archives News. “Then I read the caption, and it said the year—and that was World War I.”

The original image from February 12, 1919, is part of the series, American Unofficial Collection of World War I Photographs, 1917–1918. It depicts nine Black soldiers of the 369th Infantry Regiment aboard the USS Stockholm, awaiting arrival in New York City following the armistice that ended the war.

“They have that superhero look to them. They’re kneeling, like they’re about to launch out of the screen. You can feel that vibrant energy, all handsome. They all look like they’ve got the world at their fingertips,” Butler said.

Drawn in by the composition, the faces, and the Hellfighters name, Butler set out to make the quilt, which is approximately 9 feet tall by 13 feet wide.

She renders the black-and-white image in saturated tones and abundant textures, each man’s visage with a distinct combination of quilted patterns.

Butler felt a similar draw to the image as Barbara Lewis Burger, a retired National Archives Still Picture Senior Archivist, who in 2017 wrote a lengthy post for the National Archives blog "Rediscovering Black History" about the soldiers in the photo.

Through robust research (based largely on U.S. Army and New York National Guard records and Veterans Affairs burial files) Burger deepened the men’s histories beyond the photo’s caption and went on to inform Butler’s own research for the quilt.

Both Butler and Burger focused on raising the image, the names, and the history from obscurity.

“I'm so thankful that the men pictured in this image continue to receive the tributes they so rightfully deserve,” Burger said.

Butler went even further; sharp-eyed viewers will note that two of the men wear medals around their necks that aren’t pictured in the original photo.

“Some of them are wearing the Congressional Gold Medal—I put it on them,” Butler explained.

The men all wear the Croix de Guerre, awarded to the regiment in 1918 by the French government. But in creating the quilt, Butler said she wanted to perform an act of what she calls “restorative history” with her artwork.

“These young men never received that high commendation from the American Army at the time, though they got it from the French,” Butler explained. “Americans didn’t think they had the capacity to fight with them. So I said, ‘you are getting this big piece of gold bling.’ To have this piece in a museum, near the White House, with those medals on—it’s important. I needed it to be there.”

Butler based the medals on those awarded to the Tuskegee Airmen in 2007.

The same year that Butler finished the Hellfighters quilt, 2021, the 369th Regiment was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President Joe Biden. It was only the third time the medal was awarded to an African American military group (Tuskegee Airmen and the Montfort Point Marines, awarded in 2011, both from World War II).

The Hellfighters quilt will be on display at the Renwick Gallery in Washington, DC, a branch museum of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, until April. Read more about the exhibit, This Present Moment: Crafting a Better World.

Quilted Portraits

The soldiers were not alone in inspiring Butler. The artist often uses photos from federal archival records as the basis for her quilts that elevate Black history.

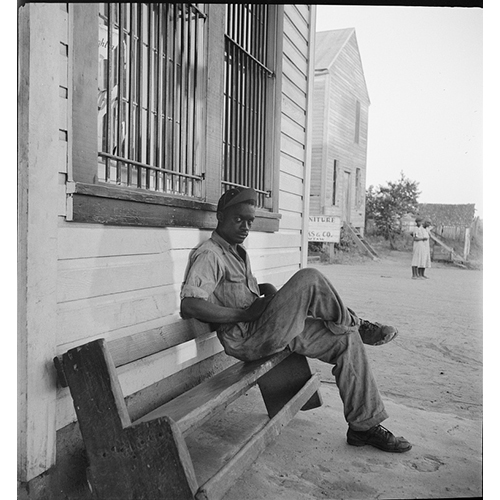

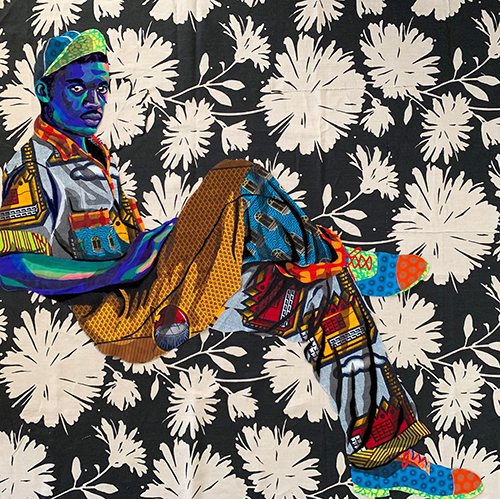

“I, too” is based on the image of a young Black man in Hillhouse, Mississippi. Photographer Dorothea Lange made the photo for the Farm Security Administration in July 1936.

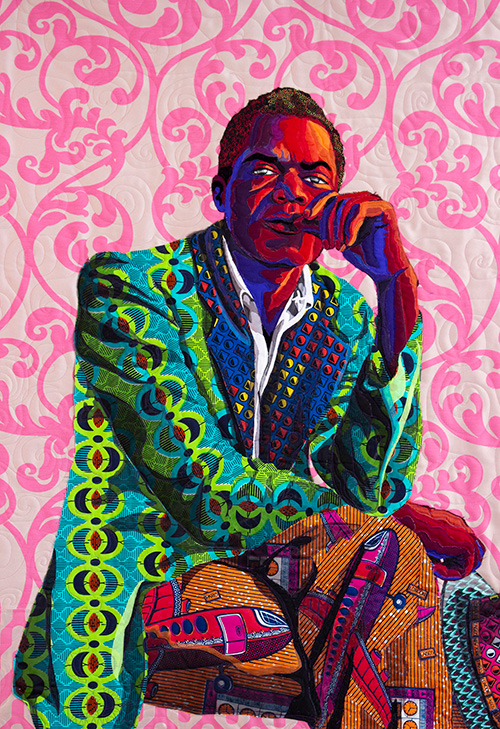

That same year, Lange made a portrait of another young Black man 60 miles south, in Greenville, Mississippi. That in turn became an “ode” to James Baldwin, in Butler's words, titled “I am not your negro.”

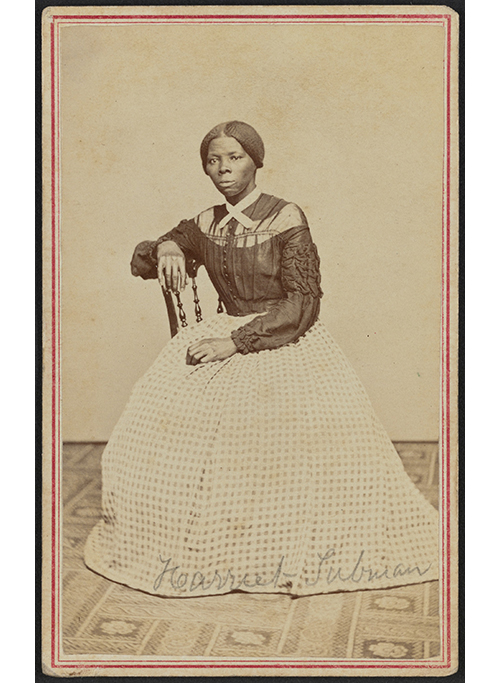

A portrait of Harriet Tubman rendered on a dusky purple background is rooted in a portrait held by the National Museum of African American History and Culture (part of the Smithsonian Institution) and the Library of Congress.

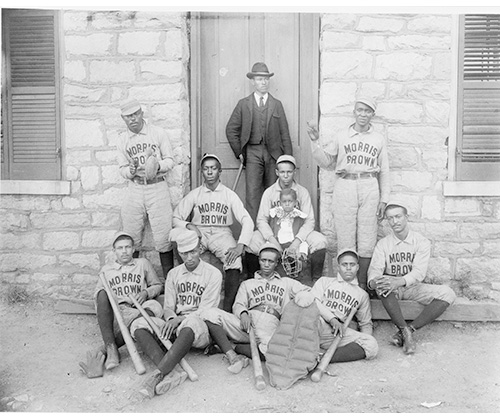

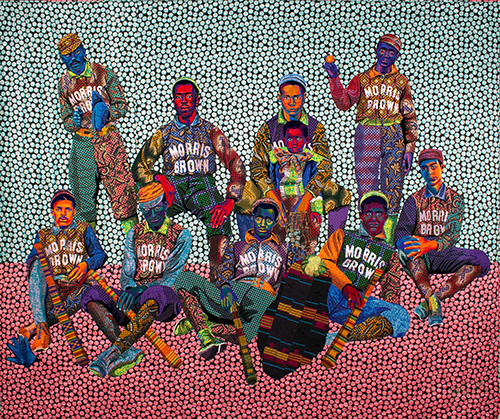

Butler also transformed an image from the Library of Congress featuring Black baseball players from Morris Brown College in 1899, which itself was from a series of W.E.B. Du Bois albums of Black Americans in Georgia shown at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900.

Special thanks to retired National Archives senior archivist Barbara Lewis Burger for her original research and assistance on this story, and writer-editor Cara Moore Lebonick for her archival research.