FDR, Archivist

The Shaping of the National Archives

Winter 2006, Vol. 38, No. 4

By Bob Clark

Franklin D. Roosevelt was a man of diverse interests and talents. At various times in his life, he considered himself to be a historian, genealogist, philatelist, ornithologist, bibliophile, tree farmer, sailor, and architect (sometimes at the same time). In the spring of 1934—just one year after taking the oath of office as President of the United States—Roosevelt developed an interest that he would retain for the rest of his life. FDR became an archivist.

President Herbert Hoover formally laid the cornerstone of the National Archives Building on February 20, 1933. FDR took office just two weeks later on March 4. In Roosevelt's first hundred days in office, 15 major pieces of legislation and executive actions were implemented to stave off the effects of the Great Depression and lead the nation toward economic recovery and reform. In 1933 and 1934, 20 new "alphabet agencies" were established to carry out New Deal programs. Many of these agencies were created even before space was allocated in Washington for their staffs.

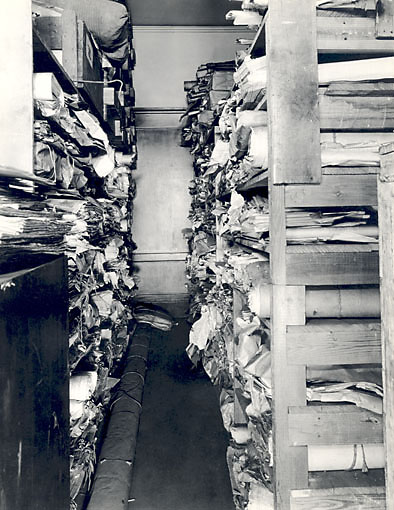

But whereas the CCC, TVA, and NRA initially were agencies without a home, by May 1934 the National Archives was a home without an agency. As the Archives building neared completion, FDR handed the task of moving forward with the creation of a National Archives agency to his trusted secretary and political confidant, Louis McHenry Howe. On May 18, Howe wrote to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes: "It is wicked the way these files are stored and left pell mell at present. That is why he [FDR] has laid it in my lap."

Action on the bill to create the National Archives Establishment moved quickly, with two competing bills in the House and Senate finally reconciled and presented to the President for his approval in June. Roosevelt signed the bill into law on June 19, 1934. The law established the position of Archivist of the United States, authorized the hiring of staff, and instructed the Archivist to gather and arrange for the transfer of appropriate archives and records of the United States Government.

His interest piqued, FDR's attention to the Archives did not end with the signing of this law. Even before he could appoint an Archivist, he began direct oversight of the new agency's activities. Early estimates for stack space in the Archives building proved to be woefully inadequate to meet the storage needs of the Archives, especially given FDR's view that the agency should permanently hold materials of lasting historical value as well as gather and manage the operational records of the government.

When it was suggested that the new building's interior courtyard be filled with additional stacks that would double the Archives' storage capacity, the President quickly concurred in a September 10, 1934, memorandum to Secretary Ickes: "I approve proceeding with the allotment for stacks in the court of the Archives Building. Before final allotment, however, will you please be sure we are violating no law? Someone told me that by some Act of Appropriation the Archives Building is limited to historic archives and cannot be used for ordinary government records and files."

Ickes, who at the time administered the public works funds designated for use in constructing the stacks, quickly assured the President that there was no illegality and that the Archives building could be used for any records of any agency that the Archivist deemed desirable for transfer and retention. It helped, of course, that the National Archives Council established by law to advise the Archivist on such matters was composed primarily of cabinet officials who undoubtedly would accept FDR's expansive view of desirable records.

FDR continued to receive updates on the progress of core stack construction, including a professorial letter from building architect John Russell Pope who was offended that stack construction and installation was not considered to be part of his original design project and that he would not have a role. After receiving word from the Public Works Procurement Division that the stack work would involve "very little architecture" and could be done by government public works employees "in a minimum period of time and at much less cost to the Government than if Mr. Pope's services are employed," FDR had a dismissive note sent to Pope by his personal secretary. It surely did not bolster Pope's cause that he had transmitted an identical plea through the President's flamboyant cousin Laura Delano. A few months later, though, FDR, the architect, would personally intervene and protect Pope's overall design by barring the construction of a new sloping roof intended to provide even more stack space.

The first Archivist of the United States, Dr. R.D.W. Connor, whom the President appointed in October 1934, quickly found that FDR's interest in the Archives went well beyond bricks and mortar issues. FDR closely monitored appointments to the Archives staff and made his own recommendations for staffing. Sometimes these recommendations related to specific individuals and sometimes to more general aspects of the Archives' overall mission. Perhaps foreshadowing the work that would be done by the WPA to collect oral histories, songs, and folklore reflecting America's diversity, in July 1935 the President made the following recommendation to the Archivist: "When you get a little further along with building up a staff, I hope you will consider the possibility of appointing a Negro to work on such archives as relate to the Negro race in the United States. I think it would be a valuable gesture if it is warranted by the need." Connor responded positively to the idea, stating he would "be glad to adopt this suggestion as soon as the organization of the staff justifies it."

The President also involved himself in matters of acquisition policy—determining the types of materials to be collected and kept for permanent historical value. As the role of the National Archives evolved, FDR never hesitated to express his own thoughts as to what should be included in the Archives. When the issue of records retention reared its head, the Archivist proposed the preparation of an acquisition and disposal policy that would clear up confusion within the various government departments and agencies between records that were important for their historical or operational value and records that were of no use. The President quickly endorsed Dr. Connor's idea of an acquisitions policy: "I am delighted that you are going into the matter of the disposal of so-called useless Government papers. I hope you will keep me in touch, as you know my real interest in the subject."

Of particular concern to the President was the preservation of motion picture film. In October 1935, he wrote to Connor: "I am thoroughly and unequivocally in favor of preservation of these definitely historic records." But his preservation desire was tinged with caution: "Nevertheless, I want to be wholly on the safe side in regard to fire and until we know more about the subject, I hesitate to have films under the same roof with the manuscript, typewritten and printed records." He then proposed as an alternative the construction of underground vaults below Constitution Avenue and suggested that "the Navy and also the Army could give you much information in regard to the protective storage of explosives and inflammables."

And revealing the inclusive nature of Roosevelt's concept of historic records, after listening to a new audio recording technique of one of his fireside chats and of an address before Congress, he advised the Archivist that he believed audio recordings to be a "new and increasingly valuable addition to the preservation by you of the Nation's archives."

Undoubtedly, the experience and knowledge that President Roosevelt gained through his involvement in the early years of the National Archives led directly to his evaluation of his own massive collections of books, prints, historic manuscripts, family papers, personal and official papers, and memorabilia. In 1938 the President announced his intention to construct a fireproof building on the grounds of his estate in Hyde Park to hold these collections and make them available to the American people. The building was built with privately donated funds and upon completion was transferred to the government to be maintained by the National Archives, thus setting the precedent for all presidential libraries that would follow.

In accepting the nation's first presidential library on June 30, 1941, Archivist of the United States R.D.W. Connor declared that "The raw materials of history are the records of past human affairs, and only when such records have been preserved and made available to him can the historian truly reconstruct and interpret the past. It must have been some such thought that inspired the idea that finds concrete expression in this library which we dedicate today."

"Franklin D. Roosevelt, the historian" and "Franklin D. Roosevelt, the statesman" came together in Franklin D. Roosevelt, the archivist, and shaped the National Archives and the Presidential library system that we know today.

Celebrating FDR at 125: Events at the Roosevelt Library in 2007

Bob Clark is supervisory archivist at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York. He received bachelor and masters degrees in history from Texas Tech University in Lubbock and a juris doctor from Syracuse University. He has been with the Roosevelt Library since 2001.

Note on Sources

This article was based primarily on records in the President's Official File 221: Archivist of the United States (OF 221) 1933–1935, and the President's Personal File (PPF): FDR Library File, in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, New York. In these files researchers will find the notes and memorandums written by President Roosevelt, Louis M. Howe, Harold Ickes, John Russell Pope, and R.D.W. Connor concerning the earliest days of the National Archives as well as original documents related to the history of the Roosevelt Library.

For more information on the history of the Roosevelt Library, see Cynthia M. Koch and Lynn A. Bassanese, "Roosevelt and His Library," Prologue 33 (Summer 2001): 75–84. The legislative origins of the National Archives are recounted in Rodney A. Ross, "Creating the National Archives," Prologue 36 (Summer 2004): 56–59.