The 1940 Census Revisited

Winter 2012, Vol. 44, No. 4 | Genealogy Notes

By Constance Potter

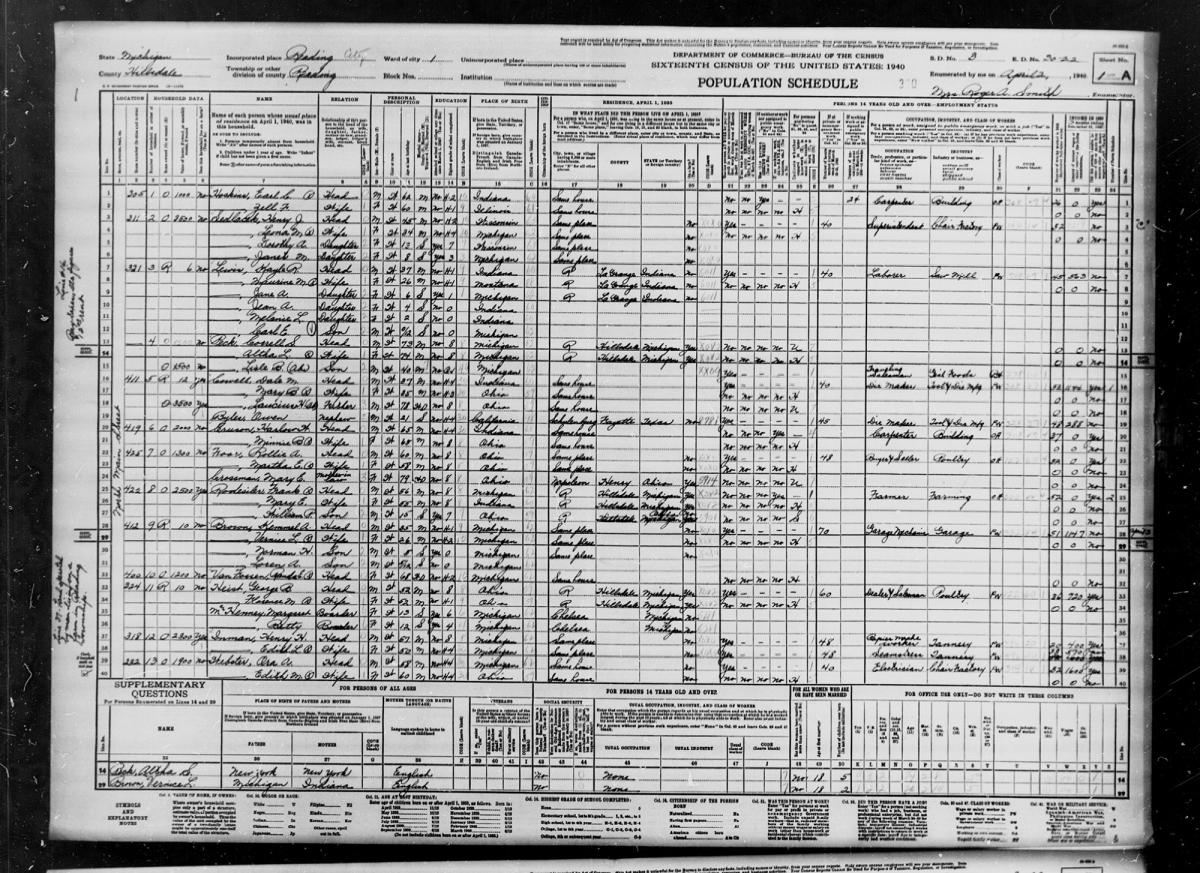

The article “New Questions in the 1940 Census” (Prologue, Winter 2010) was based on instructions to the enumerator as well as information from the statistical summaries. Although these sources provide useful information, the only way to really understand the census is to look at the actual schedules and see how people answered the questions.

Changes in Enumeration Districts

Because the 1940 census had smaller enumeration districts (EDs) than earlier censuses, the overall number of EDs increased by 27,000 for a total of 147,000. Each ED was a clearly defined place—part of a minor civil division, township, or city— that could be covered by an enumerator in about two weeks in an urban area and one month in a rural area. Rural EDs were to include no more than 1,500 inhabitants and 250 farms. The Census Bureau even considered the topography and access roads in rural areas.

Differences in Pagination from Earlier Censuses

The 1940 census is available only online, and people sometimes refer to the online pagination. It is useful, however, to look at the page numbers written in the upper right-hand corner of the census schedules.

In the 1940 census, the enumeration districts had three possible numbering systems. Pages 1A and following enumerated the people at home on April 1, or the day the enumerator first came to their home. The first set of pages rarely goes as high as 60B; most pages only go up to the 30s. After that, beginning on pages 61A and above, the census lists the people who were not at home the first time the census taker visited. If you are having trouble finding a person or address, check to see if there is a page 61; you might find who you are looking for there. You will need to compare both sets of pages to see who might be neighbors.

Pages 81A and above list transients. In column 3, where the household visitation number usually goes, the enumerators wrote a “T” for transient. The 1930 census reflected some of the dislocation of the early days of the Great Depression when it asked enumerators to look in boxcars, small rooms, closets, or any place a transient could live. In 1940, the enumerators visited hotels, flophouses, etc. on April 8. These people are listed starting on page 81A.

Marital Status

Many people have “M7” noted in the marital status column. M7 means that the person is married but not living with his or her spouse. Alma Frances Ruder, age 25, has M7 by her name. In 1935, she lived in Grand Coulee, Washington, and in 1940 she worked 26 weeks as a “nite” club singer in Seattle.

Economics and the 1940 Census

The 1940 census emphasized the country’s economic problems. The government wanted to look for data on large-scale unemployment, underemployment, and irregular incomes. The following questions reflect this interest.

Comparison of Rent and Mortgages from 1930 to 1940

The 1940 housing census did not survive, but both the 1930 and 1940 censuses asked how much a house was worth or the amount of the monthly rent. In 1930, Katherine Holley, a black school teacher from Hedgesville, West Virginia, lived with her mother in a house valued at $2,000. By the 1940 census, the house was worth $2,500. Frank H.T. Potter, a business lawyer living in Evanston, Illinois, however, saw the price of his house decrease from $18,000 in 1930 to $15,000 in the 10 years between the censuses.

Education

The 1940 census asked respondents for the first time how many years of schooling he or she had up to five years of college. The Bureau of the Census wanted to study the correlation between education and both income and jobs. At the time, many high schools graduated students at the 11th grade, so don’t assume someone did not graduate from high school just because they did not have 12 years of schooling.

Income from Wages and Salary

The government used the inormation derived from the income from wages and salary as an index of purchasing power and economic status. When looking at the income of farmers from Seward County, Kansas, you can see that these men worked 52 weeks a year and that the farmers had $0 in the wages and salary column. At first glance, it is easy to assume that none of these farmers had any income; that is not so. They have nothing in that column because they are self-employed. Check the next column that notes if someone made more than 50 dollars that year.

The O.K. Hotel in Seattle, Washington, listed many transients, most of them men. Louis Kahn, 64, single and from Germany, was naturalized and had two years of college. He had lived in the same place since 1935. He gathered junk for 15 hours the week of March 24–30. Because he worked on his own account (OA), the wages and salary column shows zero, but he put “yes” in the column asking if had made more than $50.00 in 1939.

The Census Bureau put the question on wages and salary at the end of the schedule so that if people did not want to answer that question, they would have answered the other questions. The highest salary noted was $5,000+. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a wealthy man, noted his salary as $5,000+, but future President Lyndon Johnson listed his salary as $10,000.

Emergency Work Employment Programs

One of the pillars of the New Deal was employing people on emergency work programs. These programs included the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the National Youth Administration (NYA). Census returns showed 2,400,000 people were employed by these agencies during the week of March 24–30, 1940. The records of the emergency work agencies, however, showed they employed 3,500,000 that week.

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Department of Labor selected single men between 18 and 23 for enrollment in the Civilian Conservation Corps, but the Veterans Administration could select veterans without regard to age or marital status. Enrollees served six months with the opportunity to re-enroll for up to two years. Both the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture managed the tasks assigned to the men. The War Department oversaw transportation, administration, conditioning, discipline, medical care, entertainment, religious activities, and the work details of the enrollees. The military-type training gave the War Department a group of well-conditioned and trained young men when the country entered World War II.

Other records relating to CCC workers are the CCC accident reports and inspection reports held at College Park, MD. The inspection reports provide information on company numbers, the race of the enrollees, the date the camp was established, camp location, t/he names of military personnel, the condition of the buildings and sanitary facilities, medical services, religious services, safety, discharges, and brief descriptions of work projects.

Some inspection reports include correspondence about problems with camp facilities or the conduct of enrollees and supervisory personnel. The series also includes records of special investigations arising from complaints and charges of mistreatment or fraud.

Most of the camps reported an average weight gain of between 8 and 12 pounds per man, and one camp in eastern Tennessee reported an average weight gain of 54 pounds. The availability of adequate, nourishing food at the camps eventually produced healthier soldiers during World War II.

CCC camps usually appear at the end of a county as a separate enumeration district. The schedules show only the permanent full-time employees working at the camp. The enrollees are enumerated at their homes.

Works Progress Administration

Established May 6, 1935, the WPA provided work to those in need of relief and to improve the nation’s infrastructure. Both men and women were eligible, but only one person from a household could work at a time. Applicants had to be over 18, but there was no upper age limit. The WPA also hired people with disabilities as long as their past experience qualified them for work other than manual labor. WPA workers are enumerated at their homes.

National Youth Administration

The NYA, a part of the WPA, hired students between 16 and 24 years of age. Students attending school received part-time work, and those who had dropped out of school performed community-related duties. The program focused on African American students. NYA workers are enumerated at their homes.

Supplemental Questions

In the 1940 census, the enumerators asked additional questions of two people on each page, or approximately 5 percent of the population. Many of the questions on the supplemental census had appeared in some form in earlier censuses.

One of the questions people asked staff at the National Archives before the census opened last April was whether enumerators selected famous people over others. The story of Sam Wu shows this did not happen.

Sam Wu’s entry appears on line 14, one of the lines marked for supplemental questions. Herbert Hoover, former President of the United States, is listed two lines above Wu, so Hoover was not asked the questions. Instead it is Sam Wu, his servant. The census shows that Wu, age 39, was born in the United States. (Although the Chinese Exclusion Act had not been rescinded, Wu was an American citizen because he had been born in California.) In 1935, he lived in San Francisco. Wu answered that he did not have a Social Security number. The census also shows that he had “0” years of schooling. Both his usual occupation and his job the week of March 24–30 was as a servant in a private home. He worked 60 hours the week of March 24–30. He worked 52 weeks the previous year for $780, but he also made at least an additional $50 from sources other than wages or salary.

Territories

The 1940 census enumerated the territories of Alaska, American Samoa, Guam, Hawaii, the Panama Canal Zone, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rican census is the only one in Spanish. These forms do not ask as many questions as those on the continental schedule, nor do they have supplemental schedules. The employment questions are for people 10 years of age and older; on the continental schedule, they ask employment questions for people 14 and older. The Bureau of the Census did not take a census for the Philippines.

Money from Wages for Social Security and the Railroad Retirement Board

In the early 1940s, after the completed census schedules arrived in Washington, D.C., the Census Bureau ran comparisons with estimates from the Social Security Board. The staff realized that there were “serious deficiencies in the data,” which made the tabulation on Social Security status, except for persons not in the labor force, difficult. The estimate from the 1940 census recorded 33.5 million with Social Security or railroad accounts; the Social Security Board estimated 47 million people with accounts. Follow-up research concluded that too many respondents did not understand the question or did not know the answer, and 20 million “persons failed to report on the questions.”

Enumeration of Special Groups

In some cases, census takers received special instructions based on a person’s occupation. Their instructions included these categories:

- Servants. Enumerate with the household any servants, laborers, or other employees who live with the household and sleep in the same house or dwelling unit.

- Student nurses. Enumerate student nurses as residents of the hospital, nurses’ home, or other place in which they live while they are receiving their training.

- Persons in construction and other camps. Enumerate where found, persons in railroad, highway, or other construction camps, lumber camps, convict camps, or other places that have shifting populations composed mainly of persons with no fixed address or residence.

- Soldiers, sailors, and marines. Enumerate soldiers, sailors, and marines in the Army or Navy of the United States as residence of the place where they usually sleep in the area where they are stationed. If, therefore, any household in your district reports that one of its members is a soldier, sailor, marine stationed elsewhere, do not report him as a member of that household.

- Inmates of prisons, asylums, and institutions other than hospitals. Your district may include a prison, reformatory, or jail, a home for orphans, for aged, infirm or needy persons, for blind, deaf, or incurable persons, a soldier’s home, an asylum or hospital for the insane of the feeble-minded, or a similar institution in which the inmates usually remains for long periods of time. Note that in the case of jails you must enumerate the persons there, however short the sentence. [Theoretically a person could be enumerated both at home and in the jail where he or she had spent the night.] In most prisons, the inmate number is in the column for relationship to the head of the household, and the columns on employment are not completed.

Overseas

Although the census was taken overseas, the original schedules do not survive. Because of the war in Europe, it would have been difficult to track American citizens living there.

It is important to remember that mistakes could be and were made on the census schedules. This information was taken orally, and it was easy to misunderstand what someone said. Or the enumerator may have misunderstood the question. Regardless of the reason for the error, these census schedules are permanent records of the federal government and cannot be changed.

Every census adds new questions. Researchers need to look at each census with an understanding of what questions were asked and why they were asked. With that understanding, it is easier to interpret the answers given on the schedules.

For more information on the 1940 census, see the 1940 census website.

Constance Potter is a reference archivist specializing in federal records of genealogical interest held at the National Archives and Records Administration.