Saving Major Wolf

An 1864 Report of an Execution

Summer 2013, Vol. 45, No. 2

By Bruce I. Bustard

Room 200 in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. —the Archives’ Central Research Room—is probably not many people’s idea of an exciting place.

It is dimly lit, wood paneled, with a high, ornately carved ceiling. Visitors and staff speak in whispers, amid the hum of copiers and the clicking of laptop computers. For researchers, however, Room 200 is a special place where you go to solve mysteries and make discoveries. It is where you meet the past close up.

You may have read books and articles about your subject. You may have studied printed reports and memoirs. But in the Central Research Room you can open boxes or crack volumes and look at original documents—the evidence left by participants in historic events who were there.

You wait for your cart of records to arrive with a tingle of anticipation. When you open the boxes, you are often surprised by the stories you find inside. And the documents lead to new questions about the history you thought you knew.

Just such a moment happened to me in Room 200 one winter afternoon when I was conducting research for the National Archives exhibition “Discovering the Civil War.” I was reading letters received by the Union Provost Marshal’s office in Missouri from 1864.

The duties of the Office of the Provost Marshal were not very glamorous. During the Civil War it tracked down deserters, oversaw drafts, arrested citizens charged with disloyalty, issued passes, and worked with civilian authorities in occupied areas to control saloons, gambling houses, and bordellos.

Like many Civil War records, the letters in my box were wrapped by a sheet of paper that quickly gives tells you the subject of the correspondence. The records I was reading had headings such as “Reports on Enlistments,” “Letter regarding saloons,” and “Arrest for curfew violation.”

A Surprise Account of Six Executions

Then I came upon a heading that stopped me short. It read, “Reports the execution of the six rebel soldiers held as hostages for Major Wilson and men.” Opening the letter, I found this brief note, dated October 30, 1864, from Lt. Col. Gustav Heinrichs to Acting Provost Marshal Col. Joseph Darr. It read:

"I have the honor to report that the execution of the six rebel prisoners of war mentioned in Special Order Nos 279 and 280 current series from your Office took place near Fort No 4 in this City at the specified time, and was performed to my entire satisfaction by the detail of the Provost guard in command of Capt. Jones, consisting of 44 men of the 10th Kansas and 10 men of the 41st Mo. Inf.

"The men fired at a distance of fifteen paces and five of the six were shot through the heart, and they were all instantly killed. I desire to call your attention, Colonel to the good conduct of the officers and men detailed for this unpleasant duty, and remain your obedient serv’t."

What was this? Why had “six rebel prisoners of war” been held hostage and then executed? Who were these men? And who was Major Wilson?

The execution was at odds with the images of the Civil War I’d carried with me since childhood: images of huge epic battles fought by gallant soldiers who followed a strict code of principled, if old fashioned, morality. This report seemed to tell a very different story.

The War in Missouri Different from Other Places

And in fact, the war in Missouri was different—or was, perhaps, an extreme version of events that took place elsewhere around the country. The state’s population was badly split between supporters of the Union and the Confederacy. Confederates raised irregular or “partisan” units to resist the “occupation” of their state.

At first, these groups wore uniforms and followed a formal command structure designed to keep abuses in check, but soon the lines between authorized irregular warfare and criminal behavior blurred. Missouri’s Civil War devolved into a brutal guerrilla conflict.

U.S forces used increasingly harsh counterinsurgency tactics, and civilian Union supporters raised their own informal armed groups. By 1864 it was common for roving bandits of armed men to burn homes, murder civilians who supported the other side, and steal food, clothing, and horses. Neighbors turned on neighbors—often for reasons that had little to do with the war. And those who were captured by guerrillas, like Major Wilson, could reasonably expect the worst.

While the report in the Provost Marshal’s file was mysterious, it also gave me several leads. The first lead was the reference to “Major Wilson and men.” If I could work out who this Major Wilson was, I could probably find his military service record—and possibly his pension record—in the Archives. The second clue was Heinrich’s reference to Special Orders 279 and 280. Finally, knowing that Heinrichs wrote from St. Louis, Missouri, on October 30, 1864, helped to narrow things down.

I quickly located printed versions of Special Orders 279 and 280 in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. These and other nearby documents gave me the basic facts. In the fall of 1864, Maj. James Wilson and six of his men of the Third Missouri State Militia Cavalry were captured at Pilot Knob, Missouri. A Confederate officer handed the prisoners over to guerrilla fighter Tim Reeves near Union, Missouri. The “blood stained outlaw” then “brutally murdered” Wilson and his men. In retaliation, Provost Marshal Joseph Darr chose six Confederate enlisted prisoners of war to be “shot to death by musketry.” It is these men whose deaths were noted in Heinrichs’s October 30 report.

But executing six enlisted men did not, in the minds of Union authorities, amount to “an eye for an eye.” James Wilson was an officer. Retribution for his execution demanded that a Confederate major die as well. An order was issued that “the first captured Confederate Major” be sent to the Union prison in St. Louis to face a firing squad. The unlucky Confederate was Maj, Enoch Wolf, of Major Ford’s Arkansas Battalion, who had been captured in Kansas on October 26, 1864. My next step was to read Wolf’s Confederate service record in the holdings of the War Department Collection of Confederate Records.

The uncomprehending Wolf was attached to an iron ball and anvil and told that he was to be “shot to death by musketry on Friday next between the hours of nine and eleven o’clock.” On November 8, the same day he had been informed of his execution, Major Wolf wrote to Gen. William S. Rosecrans, who commanded the Department of Missouri. Wolf asked Rosecrans to demand that his Confederate counterpart, Gen. Sterling Price, turn over “this [notorious] Bush Wacking Tim Reives [sic] to Be Executed.”

A Goodbye Letter from Major Wolf

Rosecrans did not reply. On November 10, the day before Wolf was to be executed, Wolf wrote to Rosecrans again. This time he requested a delay “of a few days” so he could “prepare for death.” The general agreed. Soon after, according to some accounts, Wolf seems to have been visited in prison by a minister to whom Wolf gave a last letter to his wife. The letter contained a line asking his wife to say good-bye to Wolf’s Masonic friends. When the minister read this line, he confirmed that the major was a Mason, rushed from his cell, and began to mobilize other Masons to assist Wolf.

Wolf’s fate became a public cause. Within less than a day, several groups—including the “Union ladies” of the City St. Louis and “faithful supporters of the Federal Government”—sent petitions and letters to Rosecrans asking that he stay the execution at least until he had determined that General Price was not going to turn over Reeves. At the same time, two St. Louis civilians telegrammed President Lincoln asking for presidential clemency, “in gratitude to Almighty God for our great victory”—probably a reference to Lincoln’s recent reelection.

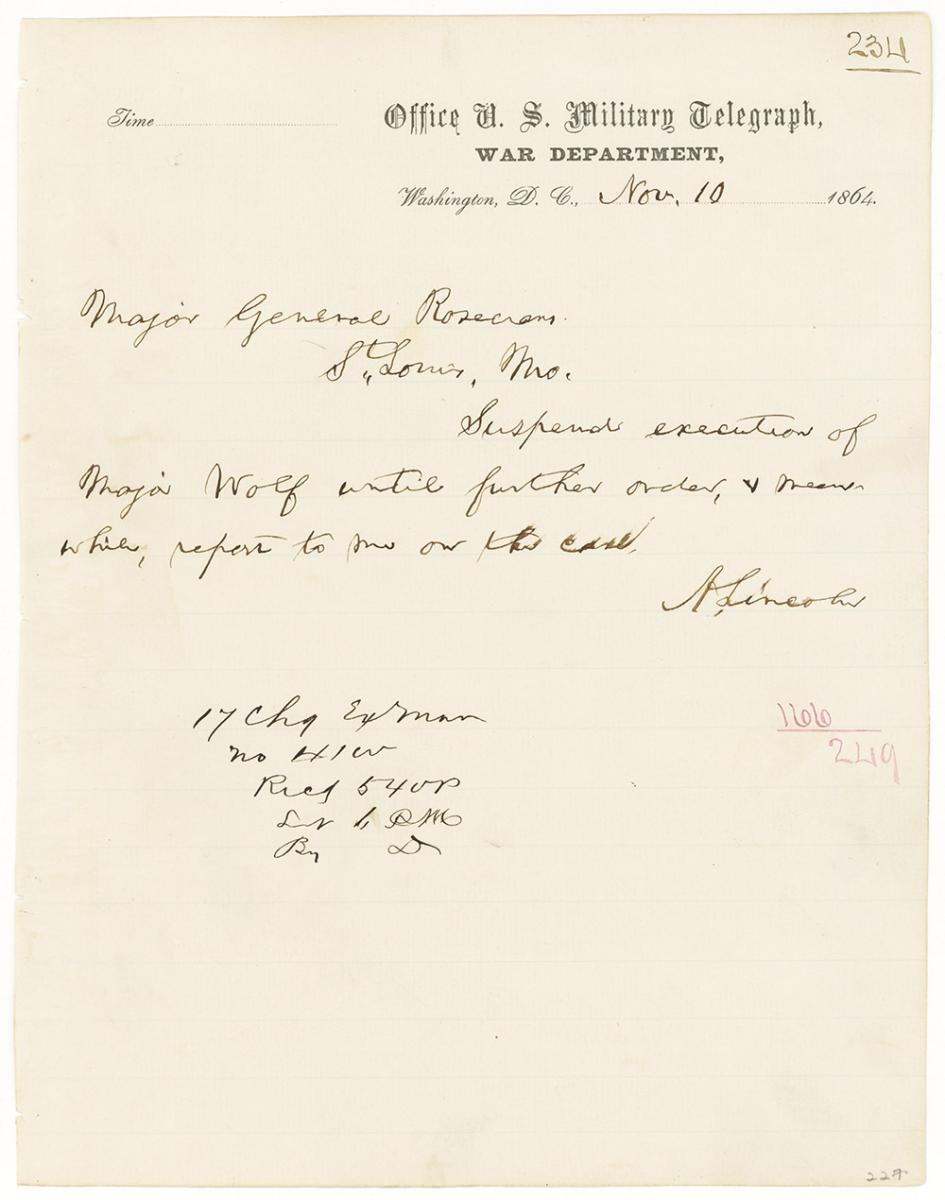

Later on November 10, in response to the petitions, Rosecrans again delayed the execution until November 25. That same day, Lincoln telegrammed Rosecrans, “Suspend execution of Major Wolf until further order.” Lincoln also asked the general to explain his actions.

As ordered, Rosecrans suspended Wolf’s execution. But he wrote the President a long letter defending his actions and chafing at being contradicted by someone almost 900 miles away who did not understand the war in Missouri. His order to execute Wolf had one goal: “to secure our prisoners from murder.” Wilson’s death had been “cold blooded murder,” and it was Rosecrans’s “right, and even duty” to “hold any organized body of men responsible for the actions of their organization.” War, he reminded his commander in chief, required the deaths of “men who have done no wrong.” Price had not prevented the “official murder” of U.S. soldiers. Only a threatened “sense of personal security” would make the point that Confederates would be held “individually responsible for the treatment of my troops while prisoners in their hands.”

Lots of Loose Ends about Major Wolf

We do not know what Lincoln made of Rosecrans’s justification, but the President’s telegram did save Major Wolf. Although it stopped Wolf’s execution only temporarily, Wolf never faced a firing squad—probably because Rosecrans was relieved of his command in January 1865. The new general, Grenville Dodge, took no further action. Wolf was eventually transferred to the Union prisoner-of-war camp on Johnson’s Island, Ohio. On February 24, 1865, he was exchanged for other prisoners at City Point, Virginia. There is no record that Tim Reeves was ever held responsible for the deaths of Major Wilson and his men. Enoch Wolf died on October 20, 1910, at age 83 in Myrone, Arkansas.

The murder of Major Wilson and his men, the execution of six innocent Confederate enlisted men, and the saving of Major Wolf, raise several weighty questions:

- Was Major Wolf simply the lucky beneficiary of Lincoln’s compassion?

- What role did Wolf’s status as an officer play in how Union’s military justice played out?

- Was the vicious guerrilla war in Missouri exceptional, or does it point to new directions for Civil War historians?

Whatever the answers to these questions, the records brought to Room 200 in the National Archives Building will undoubtedly be essential to discovering them in the future.

Bruce I. Bustard is senior curator at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. He was curator for “Searching for the Seventies” and for “Attachments: Faces and Stories from America’s Gates” in 2012. He was lead researcher for the “Discovering the Civil War” exhibition in 2010.

Learn more about . . .

Note on Sources

The initial report of the execution of the six Confederate prisoners may be found in entry 2786, Letters Received, Department of the Missouri, part 1, Records of U.S. Army Continental Commands, 1821–1920, Record Group (RG) 393.

Major Wilson’s compiled military service record is held in the Records of the Adjutant General’s Office 1780’s–1917, RG 94. Wilson served with the Third Missouri State Militia Cavalry. Enoch Wolf’s career with Ford’s Battalion of the Arkansas Cavalry as well as the campaign to save him is detailed in the service records in the War Department Collection of Confederate Records, RG 109.

The telegrams to President Lincoln asking him to save Wolf are in War Department records, Telegrams Received by the Office of the Secretary of War, Telegrams addressed to the President. Lincoln’s order suspending Wolf’s execution is also among War Department records, but in the series Telegrams sent by the President, RG 107.

General Rosecrans’s letter to Lincoln is among the Letters Sent by the Department of Missouri in the Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, Department of the Missouri, November 1864, RG 94. Enoch Wolf’s son, E Knox Wolf, published an account of his father’s story in the August 1910 issue of Confederate Veteran.

The most comprehensive study on the war in Missouri remains Michael Fellman’s Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War (1989). It should be supplemented by the more recent book by Daniel E. Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (2009).