The Rediscovered Life of the 'Lost Soldier of Chickamauga'

By Dena Lombardo and Victoria Macchi | National Archives News

Editor’s note: This is part 1 of 2 on the Civil War pension file of Hugh Thompson. Read accounts from the National Archives staff who worked on the project in part 2, NARA Behind the Scenes: The Rediscovered Life of the “Lost Soldier of Chickamauga.”

WASHINGTON, April 17, 2020 — Henry Thomson was living on a farm in Pearlette, KS, when a Springfield, OH, newspaper published a one-column piece on May 3, 1887, about his relentless search to recover his identity.

The Civil War veteran wanted his memories back. He sought his family, his former comrades, any details to fill in the recent decades since he developed amnesia after a blow to the head in the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863. The Champion City Times article (National Archives Identifier: 165322564, p 86). would become a catalyst for Thomson to learn his given name—Hugh Thompson—and unfurl much of his past. His entire pension file is now digitized for the first time and available online in the National Archives Catalog; at more than 2,000 pages, the Thompson file is the largest Civil War pension record found in the National Archives to date.

Three boxes and nine folders of records told much of Hugh Thompson’s story: how he left his father’s farm to fight in the Civil War as a private in Company H, 15th Ohio Infantry Regiment; was identified as missing in action and presumed dead after his head injury; then disappeared for more than 20 years. When he resurfaced, he faced a bureaucratic fight with his one-time wife Jane for his pension, which his father was also trying to obtain.

“With its photographs, depositions, newspaper clippings, and other documents, this pension file is an amazing find for historians and genealogists,” said Catherine Brandsen, head of the National Archives Innovation Hub, where the digitization took place. “Getting this file online helps us share Hugh Thompson's story with everybody.”

The investigation to determine whether the veteran would be eligible for a pension—if he was even the real Hugh Thompson—took years. Skepticism surrounded his story. His uncertainty about life events, his varying stories of who his children were, and his numerous marriages made investigators leery.

"A remarkable story is told by the claimant," one investigator wrote in 1890. He described a man who roamed the Midwest in the early 1870s, working whatever jobs he could get, "all the time keeping up an effort to learn who he was" (National Archives Identifier: 165322564, pp. 94–95). The case, he added, was “loaded with doubts and suspicions. (p. 115).

Over the 35-page report, the agent comes to believe that Henry Thomson and Hugh Thompson were indeed the same person, "beyond a shadow of a doubt.” That assessment and granting the pension, however, took an arduous reconstruction of his life “from 1866 or 1867, down to the present time” (National Archives Identifier: 165322564, p. 115).

“This leaves a gap of four years, which I do not believe will ever be bridged," the investigator concluded.

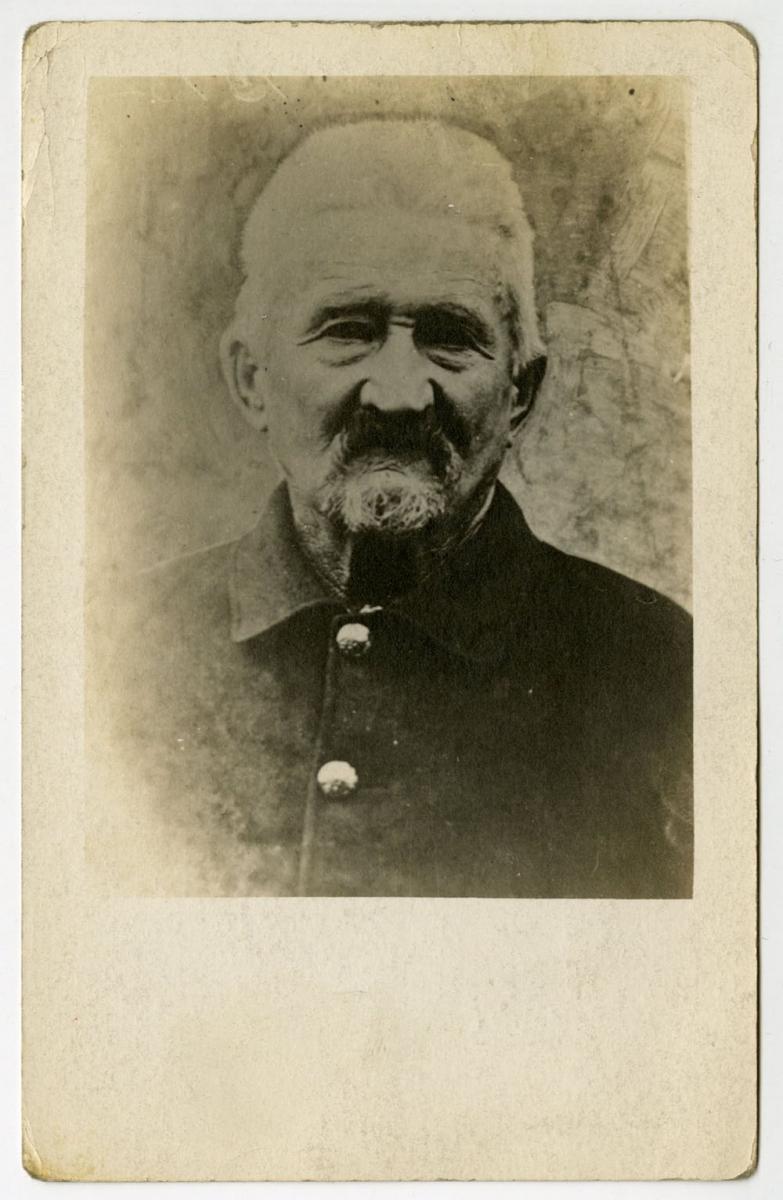

An analysis of photographs and a lengthy investigation solidified the proof that the soldier nicknamed ''Shorty” was indeed the same man as the Kansas resident.

The drama of the soldier’s story was not what first drew staff’s attention, however. It was the novelty of the file’s size. For archives technician Emily Zurlo, the project began as an assignment from a supervisor. A member of the public requested the pension file for an Ohioan named Hugh Thompson. The researcher knew the file was long, but she didn’t realize just how long it is—more than 2,000 pages. The average pension file is around 150 pages.

Incredulous, Zurlo said she went to the stacks to verify the size of the request. “I couldn't believe that a pension could be that long,” she said.

Zurlo carved time from her daily work over three months to digitize the pension records. Like nearly all National Archives employees, she is currently working from home full time amid the COVID-19 pandemic and is now focused on transcribing the documents.

The pension file remains in fragile condition at the National Archives Building in Washington, DC. Read more from the National Archives staff members about what can be learned from these records here. To view Hugh Thompson’s pension file, or help tag and transcribe the documents, visit the National Archives catalog.

See a selection of documents from Thompson's pension file in the gallery below: