Brother vs. Brother, Friend against Friend

A Story of Family, Friendship, Love, and War

Spring 2013, Vol. 45, No. 1

By Jay Bellamy

July 2013 marks the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg—the battle that many believe signaled the beginning of the end for the Confederacy.

It has often been said that the Civil War pitted “brother against brother and friend against friend.” This was never more true than in the case of Wesley Culp and Jack Skelly, two young men who grew up together in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, before the start of the war in 1861.

John Wesley Culp—born in 1839 and named for the founder of the Methodist Church—was the third of four children born to Easias “Jesse” Culp and Margaret Ann Sutherland Culp. Wesley was especially close to his two sisters, Barbara Ann and Julia, who probably felt protective of him since he was much smaller than most of the other boys and most likely endured a great deal of teasing and bullying.

Johnston “Jack” Hastings Skelly, Jr., was two years younger than Wesley and also a third child. There were 10 Skelly children in all, although two died before reaching the age of four. Skelly Sr., a tailor by trade, had moved to Gettysburg in 1836. The following year, he married Elizabeth Finnefrock, and the two then settled down to begin a family and start a tailoring business in Gettysburg. Skelly made sure that all the children were taught the trade, including the girls.

As boys growing up together, Wes Culp and Jack Skelly became fast friends. They would often go exploring on Culps Hill, a prime piece of Gettysburg real estate owned by Henry Culp, a family relative. In many of their excursions they included young Mary Virginia Wade, better known to her friends and family as Jennie.

The Wade family was not held in very high esteem in the Gettysburg community. James Wade, Jennie’s father, often found himself on the wrong side of the law. After being found guilty of larceny in November 1850, Wade spent two years in Eastern Penitentiary in Philadelphia. Mary Wade then asked that her husband be declared “very insane” and placed in the Adams County Alms House, where he remained until his death in 1872.

As the years passed and the three childhood friends grew into their teens, Jack and Jennie’s feelings for each other intensified. Wesley, however, had little time to feel neglected, as he had taken a job with C. William Hoffman, a local carriage shop owner. When Hoffman decided to move his business to Shepherdstown, Virginia (now West Virginia) in 1856, he asked Wesley and several other employees to go with him. Wesley’s brother William declined, but Wesley quickly agreed to relocate, as did Charles Edwin Skelly, Jack’s brother.

The War Begins, Choices Are Made

By the end of the 1850s, the country was in turmoil. Southern states threatened secession if a Republican was elected President in 1860, and John Brown’s failed raid on the Harper’s Ferry arsenal in 1859 clearly showed the division within the country.

While the South denounced Brown as a lunatic and murderer, many in the North mourned his execution and hailed him as a fallen martyr. When Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, was elected in 1860, Southern states began seceding, beginning with South Carolina and followed by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas.

On April 12, 1861, batteries of the new Confederate army opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. After 34 straight hours of bombardment, Sumter’s commander, Maj. Robert Anderson, reluctantly surrendered the fort. The first shots of the Civil War had been fired, and it was now time for allegiances to be made and sides taken. One of those forced to make a choice was Wesley Culp, formerly of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Before the war, Wesley had registered with the Hamtramck Guards, a social and military organization that many young men in Shepherdstown joined to meet and make new friends. When war broke out and the other Gettysburg natives prepared to head north, Wes informed Edwin Skelly that he would not be returning with them. He had made a new life for himself in Virginia, he explained, and was prepared to stay “come what may.”

When informed by the returning Gettysburg boys that Wesley had chosen to remain behind in Virginia, William Culp was furious. For the rest of his life, so the story goes, he would not allow his brother’s name to be mentioned in his presence. On April 20, 1861, just eight days after the attack on Fort Sumter, Wesley enlisted with the Confederate army at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. (Harper’s Ferry would not become a part of West Virginia until that state’s admittance to the Union in 1863.)

Soldiers Answer the Call, and a Letter Is Sent

When the call for Union soldiers was announced and four more Southern states had seceded, Jack quickly answered the call.

“My country needs me, Mother,” he explained when asking for permission to enlist. “May I go?”

“Yes, my boy,” she answered, “and may God bless and keep you.”

Having secured his mother’s permission, Jack, along with William Culp, enlisted with the Second Pennsylvania Volunteers and was mustered into service on April 29, 1861.

It didn’t take long for the three young men to fight on the same field of battle. On July 2, 1861, the Second Pennsylvania was engaged in action at Falling Waters in Berkeley County, Virginia, against Confederate forces commanded by Col. Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson.

Wesley’s militia unit, the Hamtramck Guards, had been mustered into service as the Second Virginia Infantry (soon to become known as the famous “Stonewall Brigade”) and was part of the rebel force facing the Union divisions of Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson. Although the battle ultimately proved a Union victory, Patterson was relieved of his command after failing to block the rebel retreat to Winchester.

After their 90-day enlistment expired, William and Jack returned home to Gettysburg, where they were most likely treated as returning war heroes. By September, however, they had both decided to re-enlist for a three-year period with the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry. We can only assume that Jack was present for the next three months, as his service records at the National Archives in Washington, D.C, are not entirely clear on this matter. Under the question of absent or present, it simply reads: “not stated.” Wesley’s service records, however, show him as “absent on furlough” for the months of January and February 1862. The next report, dated June 13, shows him “taken prisoner while absent on furlough.”

With Wesley being held as a prisoner of war, William managed to put aside his ill feelings toward his brother just long enough to visit him in a Union prison camp. He wrote to Barbara Anne that Wesley was doing well under the circumstances and hoped to be released soon. On August 5 Wesley was released in a prisoner exchange. He rejoined his unit after walking back to Shepherdstown and first enjoying a brief period of rest and relaxation.

Meanwhile, Jack was receiving letters from his mother—who was concerned about her son’s relationship with Jennie—informing him that word on the street had Jennie keeping company with several gentlemen callers late into the night.

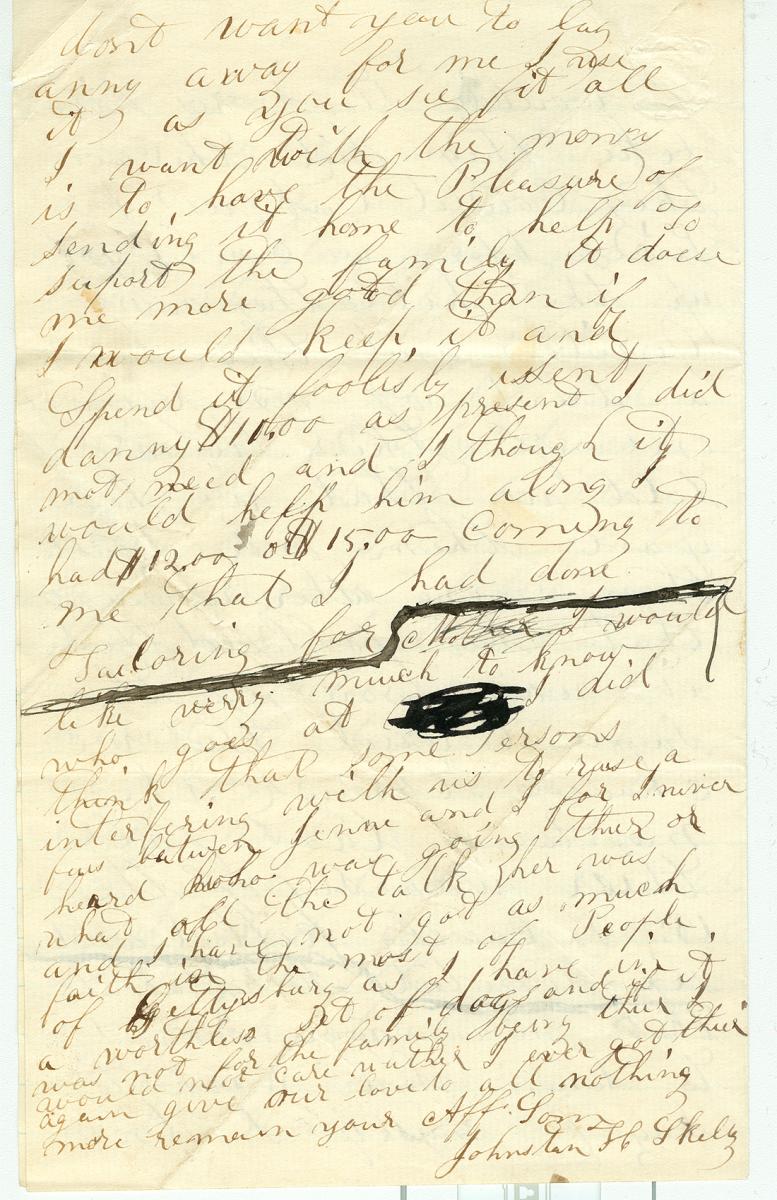

In reply to his mother, Jack mentioned that he would very much like to know who was supposedly visiting Jennie. He stated that he did not have as much faith in most of the people of Gettysburg as he did in a “worthless set of dogs” and that if it were not for family in Gettysburg, he wouldn’t care if he ever returned home again. He believed that these rumors were being spread by “some persons interfering with us to raise a fuss between Jennie and I.”

Lee’s Army Heads North Toward Historic Battle

Nearly a year later, Jack informed his mother that he had questioned Jennie about the allegations, and although she admitted to entertaining company on occasion, she denied keeping late hours with anyone.

This admission was apparently good enough for Jack, as he then went on to admonish his mother: “You should have said something to me when I first commenced going there [referring to his own visits with Jennie] if you did not like it.”

Jack further reiterated that it was his honest belief that someone was just trying to raise a fuss between him and Jennie and that as far as he was concerned, the matter “was all over for the Present and I hope for the future.”

After August 1862, the service records for Jack, William, and Wesley show them all present until the May–June 1863 report for the 87th Pennsylvania. Under remarks, it says for Jack: “Missing in action on June 13, 14 & 15, 1863.” In truth, Jack was lying in a Confederate hospital after being critically wounded during the Second Battle of Winchester, also known as the Battle of Carter’s Woods.

(Union newspapers traditionally named battles for landmarks near the actual battlefield locations, whereas Southern papers would use the name of the town closest to the battle.)

It was earlier that month, on June 3, that Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia departed Fredericksburg, Virginia, to begin their second invasion of the North. Lee and his army had attempted their first incursion into Union territory the previous year, when they were narrowly defeated at the Battle of Antietam in Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862.

Between June 12 and 15 of 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia and the Union Army of the Potomac were engaged in battle near Winchester, Virginia, with Confederate forces prevailing in the end. For the second time, Wesley and William Culp and their friend Jack Skelly were present on the same field of battle. A third Culp, William and Wesley’s cousin, David, was also fighting for the Union and was taken prisoner during the battle.

Another Union soldier taken prisoner that day was Edwin Skelly, who along with his younger brother Jack and neighbor William Culp had signed up with the 87th Pennsylvania almost two years earlier. Not to be outdone by his two sons, Johnston Skelly, Sr., whose unit was not present on this day, was fighting with the 101st Pennsylvania Infantry—truly making this war a Skelly family affair.

Jack Skelly Hurt in Retreat, Gives Letter to Wesley Culp

After being ordered to surrender, Jack was struck in the arm by a minié ball and severely injured while attempting to flee from advancing rebel troops. When Wesley learned of Jack’s injury, he visited his friend in a Confederate field hospital, where it is said that Jack gave Wesley a letter to deliver to Jennie Wade if he ever made it back home to Gettysburg.

Historians and everyday students of the Civil War have speculated on the contents of this letter for generations. Many claim it was an expression of devotion or even a marriage proposal, but no one can be sure. There is little doubt that Wesley was asked to deliver some kind of message to Jennie, and within just weeks, remarkably, he had the chance.

For nearly a month, Lee’s army marched through Virginia and Maryland, arriving in Pennsylvania at the end of June. Following close behind were Union troops under the command of Gen. Joseph Hooker, who would be replaced during the pursuit by Gen. George Meade. Having been informed by a spy that the Union army was close behind, Lee ordered all troops to converge at a central location. Because multiple roads led into town from all directions, Gettysburg seemed to be the logical meeting point.

The Second Virginia Infantry, including former Gettysburg resident Wesley Culp, was part of Lee’s invading force. Wes had finally come home, but he was now considered by many, including family, to be a traitor to his town and country. Several family members had even threatened to shoot him on sight if they ever saw him again. But Barbara Anne and Julia were still devoted to their brother, regardless of which side he chose in this terrible war. When Wesley showed up at Barbara Anne’s door on the night of July 1, she greeted him with open arms.

After spending several hours with his sisters, enjoying a nice meal and catching up on the local news, Wes bid them a good-night. Barbara Anne and Julia begged him to stay until morning, but he insisted on leaving. His commanding officer had graciously given him a pass to visit with his family, he explained, but he was still expected to return to camp that evening.

Before departing, however, he mentioned that he had a message to deliver to Jack Skelly’s mother and hoped to be able to visit again the following morning. Descendants of Jennie’s sister Georgia believe Jack’s message was to inform his mother of his intention to marry Jennie in September when he was eligible for furlough. When asked if he had a message for anyone else in Gettysburg, Wesley simply avoided the question.

“Never mind,” he told them, “you’ll get all the news from Mrs. Skelly.”

Barbara Anne and Julia offered to visit Mrs. Skelly on his behalf, probably out of concern that Wesley might be spotted in town, but he was adamant about delivering the message himself.

Wesley was unable to follow through on his plan to return. Before he could visit Mrs. Skelly or Jennie Wade, his short life tragically came to an end.

The Mysterious Death and Burial of Wesley Culp

There has been a great deal of controversy over the years as to where and when Wesley Culp was killed. While many believe he died on July 3 near the hill bearing his family name, others insist he was killed on July 2 after looking up from behind a large boulder to see what was happening around him. Although the July– August service record for Wes reads: “killed in battle at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863,” Confederate recordkeeping was notoriously haphazard.

Supporting the July 2 date is the report of Pvt. Benjamin Pendleton, who served in Wesley’s unit. Pendleton knew Wes from their days in Shepherdstown and had even met Julia on several occasions when she visited her brother before the war. Pendleton claimed he had helped Wesley obtain a pass into town that first night and then joined him on the skirmish line the next morning. As the line advanced, Pendleton stated, Wesley was shot and killed. When Pendleton delivered the news to Barbara Anne and Julia the next evening, he described Wes’s grave as being somewhere under “a crooked tree.” After a thorough search, however, the family never located his grave. All that was found was the stock of his gun, which had been modified to accommodate his 5´ 4´´ frame, with his initials carved into it.

Further evidence comes from a 1913 Pittsburg Gazette Times article written by George Fleming. Fleming had spoken to a number of individuals who claimed to have been with Wes at the time of his death. He wrote:

“When Geary’s division of the Twelfth Corps had entrenched the line, the right of the Union army on Culps Hill, at 8 o’clock on the morning of July 2, Gen. Geary advanced a strong skirmish line to the foot of the hill along Rock Creek. From the Twenty-eighth Pennsylvania the whole of Company G of Sewickley, under First Sergeant Thomas J. Hamilton, was on the line, and they had a hot day of it, being driven in at dusk by the advance of Johnson’s whole division, but Wes Culp had been killed in the morning’s skirmishing in their front and was buried by his comrades where he fell ” [emphasis added].

The last piece of evidence comes from Barbara Anne herself, who supposedly confirmed the July 2 date to her daughter Margaret years after her brother’s death.

While it may be romantic to think that Wesley Culp died at Culps Hill on July 3, the most compelling evidence points to his death occurring on the morning of July 2 somewhere east of Rock Creek, on or near the farm of Christian Benner. We will probably never know what happened to his earthly remains.

Rumors have spread over generations that Barbara Anne and Julia either found his body and had him secretly buried at Evergreen Cemetery or put to rest somewhere near the family farm. Another story claimed that, after finding him, they chose to leave him where he was, afraid that any proper gravesite might be vandalized by those who still harbored ill feelings toward him.

Others claim that his body was found and buried in a Confederate cemetery in Virginia, but there is no convincing evidence, and no family member has ever spoken about this possibility. There is a grave marker for a Pvt. John Wesley Culp in the Hollywood cemetery in Richmond, but it is most likely a misidentified Confederate soldier who was moved to Richmond in 1872, when many of the Confederate dead originally buried at Gettysburg were returned to the South.

Jennie Shot in Her Sister’s Home, and Jack Skelly Dies of Injuries

With much of the battle’s first day’s action taking place near the center of town—where the Wade home was located—Jennie’s family took refuge at the home of her sister, Georgia Wade McClellan, which was south of town. Mrs. Wade and Jennie helped take care of Georgia’s newborn baby boy while her husband fought for the Union. Also moving to the McClellan house were Jennie’s younger brother Harry and Isaac Brinkerhoff, a six-year-old crippled child the family looked after during the day.

For the first two days of the battle, Jennie baked bread and biscuits for the tired Union soldiers. She also made numerous trips to the well to fill the never-ending procession of empty canteens. Although others in the neighborhood were charging for goods, Jennie refused to do so.

The McClellan home was not the safe haven the family hoped for. To the left was Cemetery Hill, where fighting had been hot and heavy on the night of July 2. The small brick house now sat between Union and Confederate lines.

On the morning of July 3, Jennie was preparing hot biscuits for Union soldiers camped in front of the house. Earlier that morning, a bullet had crashed through the window of Georgia’s room, struck a bedpost, and came to rest on the pillow where Georgia lay sleeping with her baby.

Jennie declared just moments later that if anybody was to die in the house that day, “I hope it is me, as George [Georgia’s nickname] has a baby.”

Shortly after 8:30 a.m., as she stood in front of the stove, a stray Confederate bullet smashed through the outside door, pierced the door that opened from Georgia’s bedroom into the kitchen, and struck Jennie just below the shoulder blade before entering her heart and killing her instantly. Found inside her apron pocket was a photograph of Jack Skelly.

Back in Virginia, after lying in the Confederate hospital for nearly 30 days, Jack died on July 12. Friends and family in Gettysburg learned of his fate months later. After being reported missing in action on the May–June and July–August reports, his service record for September–October reads: “Died at hosp. [hospital] Winchester Va. July 12, 63 of wounds received in action near that place June 15, 63.” The deaths of Gettysburg boys Wesley Culp on July 2 and Jack Skelly on July 12 epitomized the notion of “friend against friend” during America’s four years of Civil War.

The Battle of Gettysburg: A Postscript

The Battle of Gettysburg was fought over the first three days in July of 1863. This single confrontation would result in over 51,000 dead, wounded, or missing in action, clearly making it the most costly engagement of the Civil War. Lee lost a third of his entire army at Gettysburg, yet through sheer resolve the rebels continued to fight another two years.

On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln traveled to Gettysburg to dedicate a new national cemetery in honor of those who had given “the last full measure of devotion.” His Gettysburg Address is widely considered to be one of the finest literary works in American history.

Wesley Culp’s brother William, whose regiment was not involved at Gettysburg, remained with the Union army until war’s end, reaching the rank of first lieutenant before being mustered out of service in 1865. David Culp and Edwin Skelly—who were both released from Confederate captivity within months of their capture at the battle of Carter’s Woods—officially ended their military service in 1864, mustering out on October 13.

A card in David Culp’s file dated October 29, 1889, shows that when he was at Camp Parole in Maryland—one of three camps designated to hold paroled Union prisoners until they could be exchanged for Confederate prisoners—he was charged with desertion after leaving camp from July 28 to October 7, 1863. The charge was later removed and changed to “absent without proper authorization” under an act of Congress dated March of 1889.

Jennie Wade was first buried in the garden just outside her sister’s house on July 4, 1863. Her body was reinterred in the graveyard of a German Reform Church in January 1864. In November 1865 her remains were relocated to her permanent resting place in the Evergreen Cemetery at Gettysburg. A monument to Jennie’s memory at her gravesite, built in 1900, is one of the most visited tourist spots in Gettysburg. It depicts a solemn Jennie rising above the many tombstones that dot the Evergreen landscape.

A mere 70 yards from where Jennie lies is the grave of Jack Skelly. Jack’s younger brother, Daniel, traveled to Winchester, Virginia, in November of 1864 to retrieve his brother’s remains for burial in his hometown. While the Civil War may have separated Jack and Jennie in life, they now rest near one another for all eternity.

Jay Bellamy is in the Research Support Branch at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland. He is a student of the Civil War, with special emphasis on the Battle of Gettysburg as well as the life of Abraham Lincoln. In 2008, he published Dear Jennie, a mystery novel based on the lives of Jennie Wade, Jack Skelly, and Wesley Culp.

Note on Sources

Service records for Wesley Culp are in National Archives Microfilm Publication M324, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served from Virginia (roll 374), War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Record Group 109 (also available online through Fold3.com). The military service records of Jack Skelly, William Culp, and David Culp are in Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s–1917, Record Group 94, National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.

The letters between Jack Skelly and his mother are in Jack’s pension file in the Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Additional information about Jennie Wade and Jack Skelly is in Cindy Small’s book, The Jennie Wade Story: A True and Complete Account of the Only Civilian Killed During the Battle of Gettysburg (Gettysburg, Pa.: Thomas Publications, 1991) and Enrica D’Alessandro’s “My Country Needs Me”: The Story of Corporal Johnston Hastings Skelly, Jr. (Lynchburg, Va.: Schroeder Publications, 2012).

My special thanks go to Bob O’Connor, author of A House Divided Against Itself and other books on the Civil War, for his many email communications with me regarding the death of Wesley Culp. I thank him for helping me to put aside old beliefs just long enough to see things from a different perspective.