Photographic Prints in the Still Picture Branch

Introduction

Our holdings consist of a substantial number of photographic print processes from the mid-19th century to early 21st century. The most prominent processes in our holdings are gelatin silver developing-out prints, followed by color chromogenic prints. Other processes include: salt prints, albumen prints, gelatin printing-out prints, collodion printing-out prints, matte collodion prints, platinum/palladium prints, cyanotypes, colotypes, and digital prints.

We do have a small number of positive photographic images on non-paper supports, such as daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and autochromes (glass support), as well as tintypes (lacquered iron support). This page focuses on photographic prints made on a paper support.

Processes

Salt Print

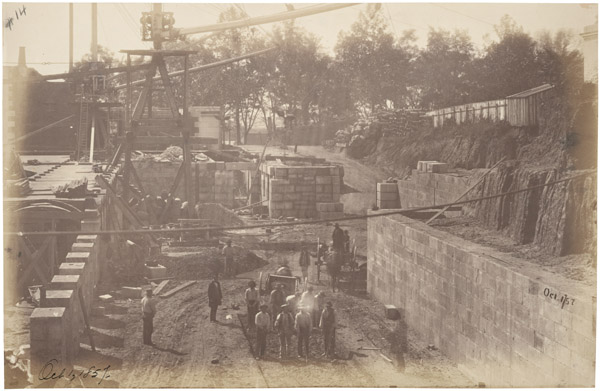

The salted paper process is the earliest photographic print process, invented by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1840. Salt prints were traditionally printed on high-quality paper without a baryta layer or binder, making the paper fibers completely visible. These prints are usually mounted and almost always have a matte surface. They can be identified by the warm image tone, with reddish brown or yellowish hues. Other common identifying characteristics are fading and image discoloration, with image tones often changing toward yellow-brown due to deterioration.

This form of photography was popular for a short period of time and remained in use until the mid-1860s.

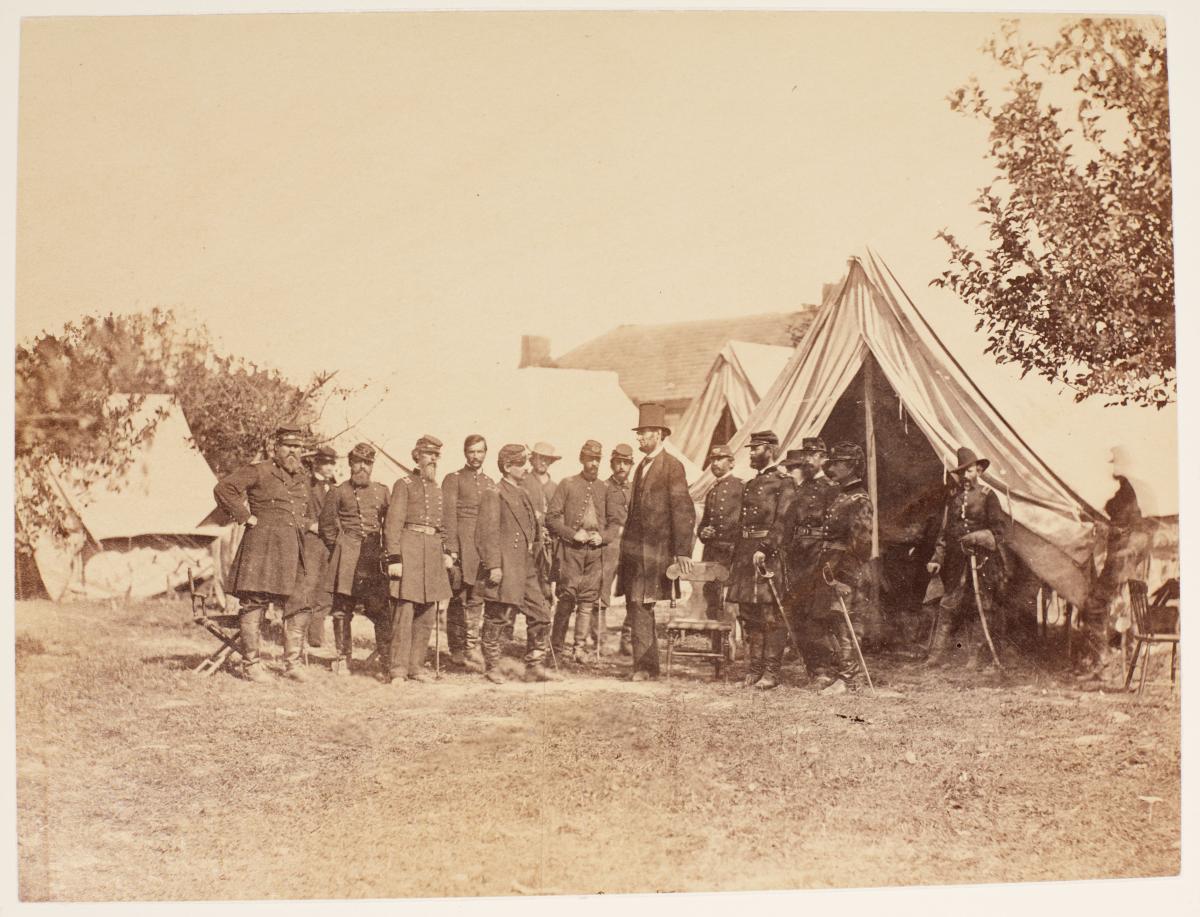

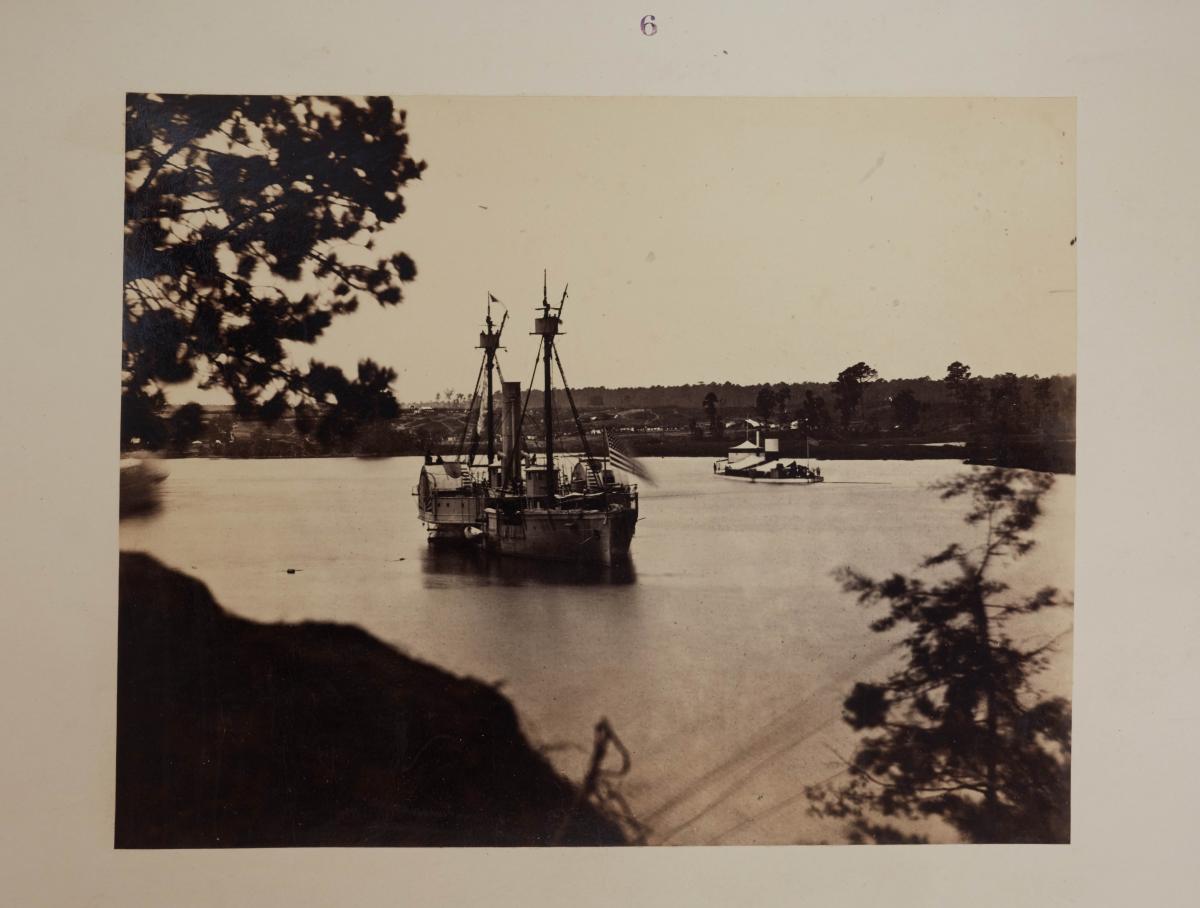

Albumen

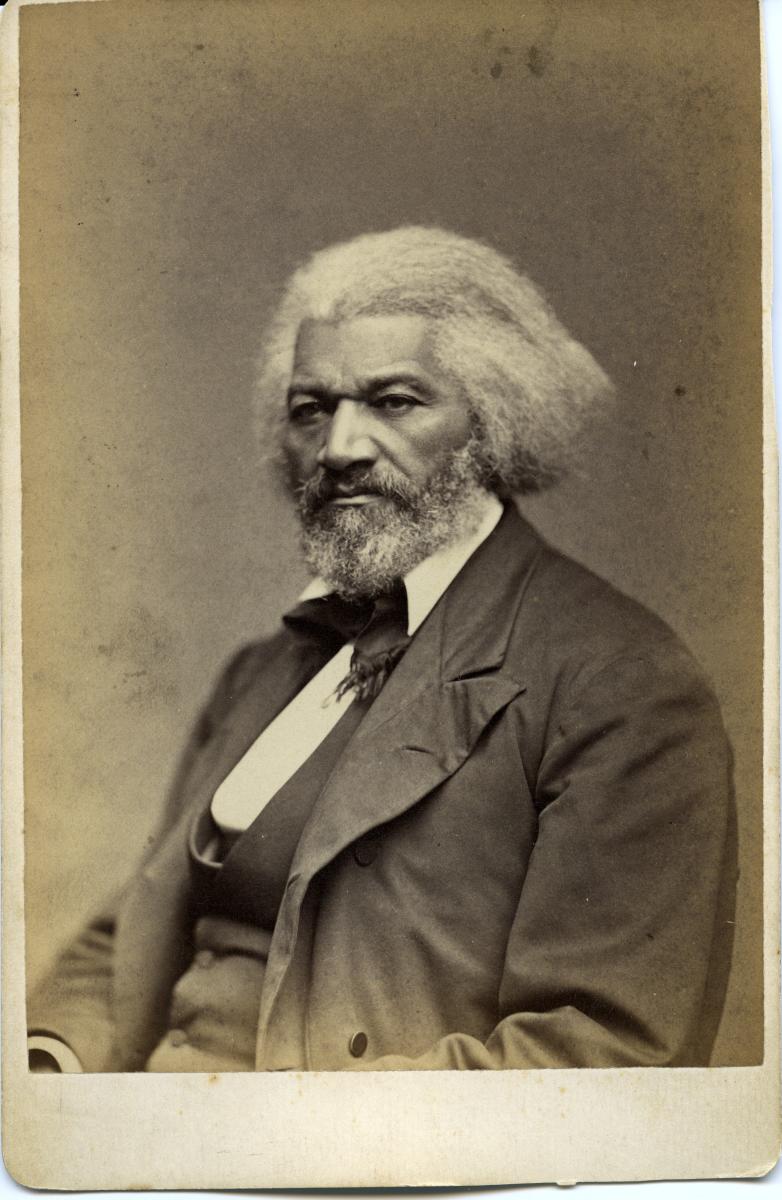

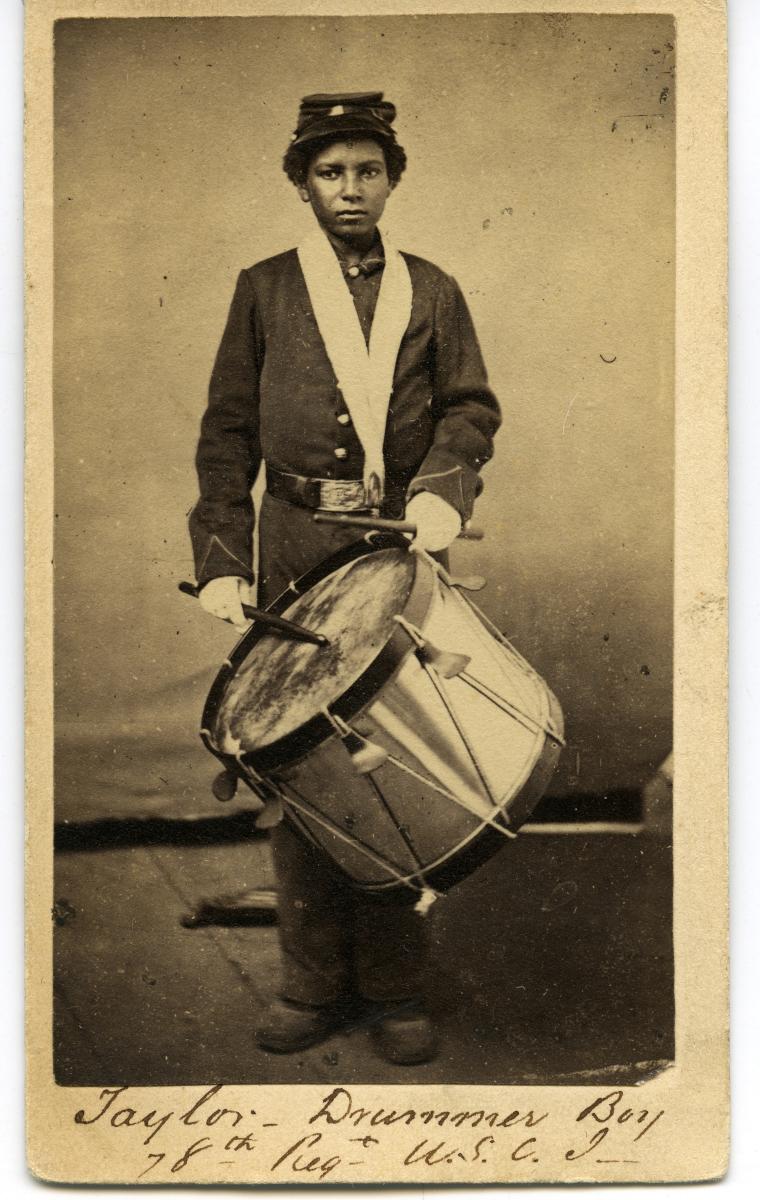

Introduced in 1850 by Louis-Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, albumen prints were the most common type of photographic print made during the 19th century. To create albumen prints, paper was floated in a mixture of fermented chloride and egg white, dried, and then floated on a solution of silver nitrate. The paper would then be placed in a frame in direct contact with the negative, where sunlight was used during the exposure process.

Albumen prints are usually mounted to a secondary support, as they are made on very thin paper stock and tend to curl severely due to the difference in absorption and desorption of moisture between the paper and the albumen binder. Often characterized by a smooth, shiny surface, albumen prints can vary in color from a warm image tone to purple-brown. Albumen prints tend to yellow over time, and in some cases, tiny cracks in the binder are visible. When placed under magnification, the paper fibers are visible.

Due to the dominance of the process, it was used for every application of photography and can be found in a wide variety of formats, such as cartes-de-visite, cabinet cards, and professional photographic albums.

Collodion Printing-Out and Gelatin Printing-Out

The collodion printing-out process (Collodion POP) and gelatin printing-out process (Gelatin POP) overtook albumen in the mid-1880s, and it can often be extremely difficult to distinguish between the two. Like the albumen print, these printing-out processes were contact printed under ultraviolet (sun) light. Unlike albumen prints, the paper fibers are not visible, as they are heavily obscured by a thick baryta layer. Reddish-brown or purplish-brown image tones and a smooth, glossy surface are characteristics that both of these processes share.

Deterioration characteristics are where these two differ, with Gelatin POPs being more susceptible to fading and discoloration, often with yellowed image tones. While Collodion POPs maintain a stable image with very little fading and discoloration, they are more susceptible to abrasions that can remove image material and expose the white baryta layer. Like all photographic processes, the levels of deterioration can be traced back to processing work performed by the photographer and environmental factors, such as storage conditions, humidity levels, and exposure to light.

Gelatin POPs outsold Collodion POPs by the late 1890s, but both would be displaced in the 1910s and 1920s by gelatin developing-out papers.

Matte Collodion Print

Most commonly used from 1895 to 1910, matte collodion prints have excellent image stability and rarely show any deterioration. These prints have a thin baryta layer, allowing the paper fibers to be partially visible which gives the prints a matte textured surface and sheen. Typically mounted, these prints have image tones that range from neutral-black to olive-black and are susceptible to surface abrasions such as scratches or cracks.

Matte collodion prints were often toned with gold and platinum, which gave them an appearance that resembled those of platinum prints, but at a much lower cost. Prints that display more purple tones indicate the use of more gold in the bath, while browner tones indicate more platinum was used.

Platinum

Patented in 1873 by William Willis, the platinum process was common from 1880 to 1930, and uses high-quality paper coated with iron and platinum salts. Platinum prints have no binder layer and were coated directly onto the paper support, resulting in a matte surface and relatively soft image.

Image transfer onto adjacent paper housings is possible if platinum catalyzes with poor quality paper, resulting in what is known as a “ghost” image. Other identifying characteristics include visible paper fibers under magnification and image tones varying from neutral black to warm brown.

Platinum prints were eventually pushed out by photographers due to the scarce and expensive nature of platinum during World War I, though they would see a resurgence in the 1960s and 1970s among fine art photographers.

Cyanotypes

Cyanotypes are easily identified by their cyan image color, Prussian blue. Cyanotypes achieve this distinct color from an iron-salt solution that is directly applied to the paper, which turns blue when exposed to light. With a single layer structure, the Prussian blue pigments rest within the fibers of the paper support, giving it a matte surface and the texture the same as the paper it was printed on.

They are literally “blueprints” – and a very similar process is still used today to make copies of architectural prints by the same name. Though the intriguing cyanotype process itself was first developed in 1842 by astronomer and scientist Sir John F. W. Herschel, most cyanotypes didn’t really hit their peak until the 1880s when amateurs started making multiple prints from their negatives for a relatively inexpensive price.

Cyanotypes are extremely sensitive to light and will fade quickly, so viewing them in our research room is very limited.

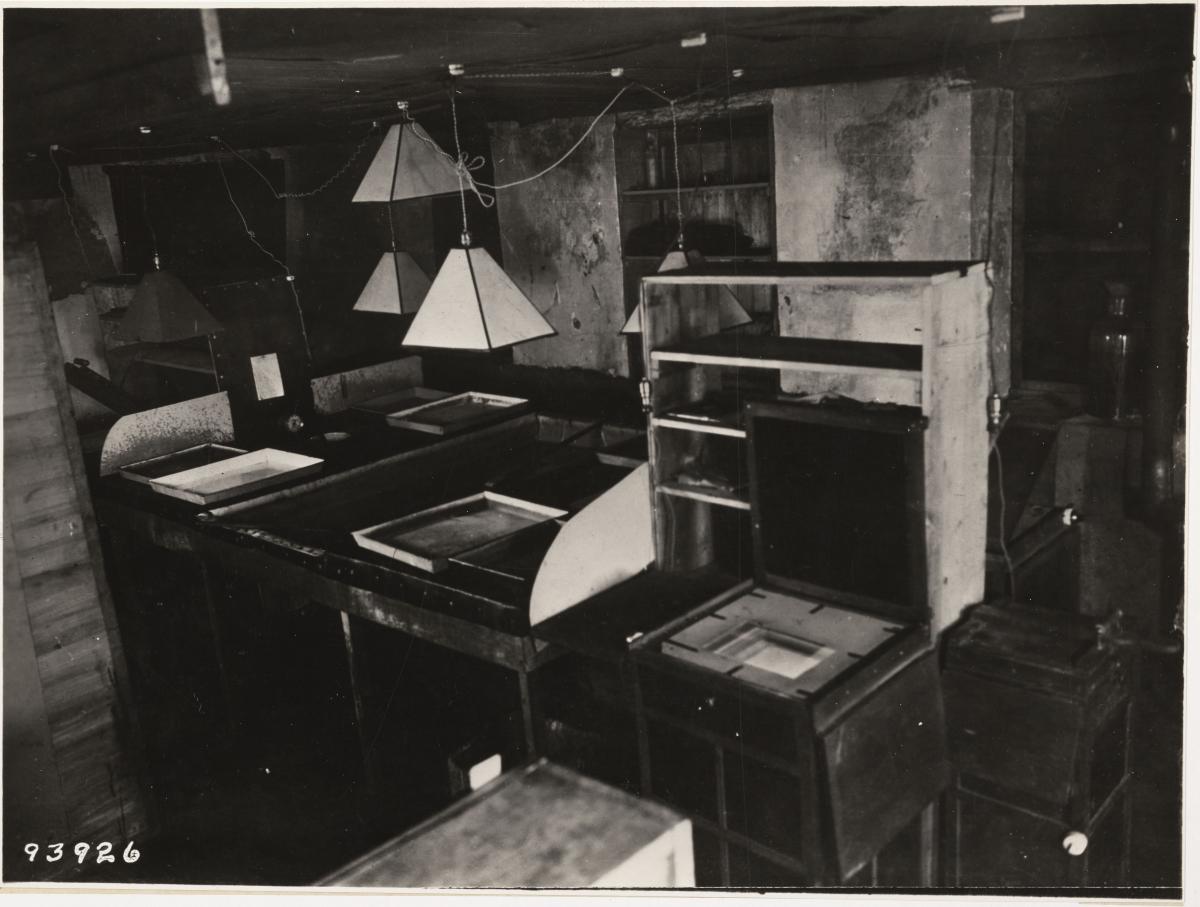

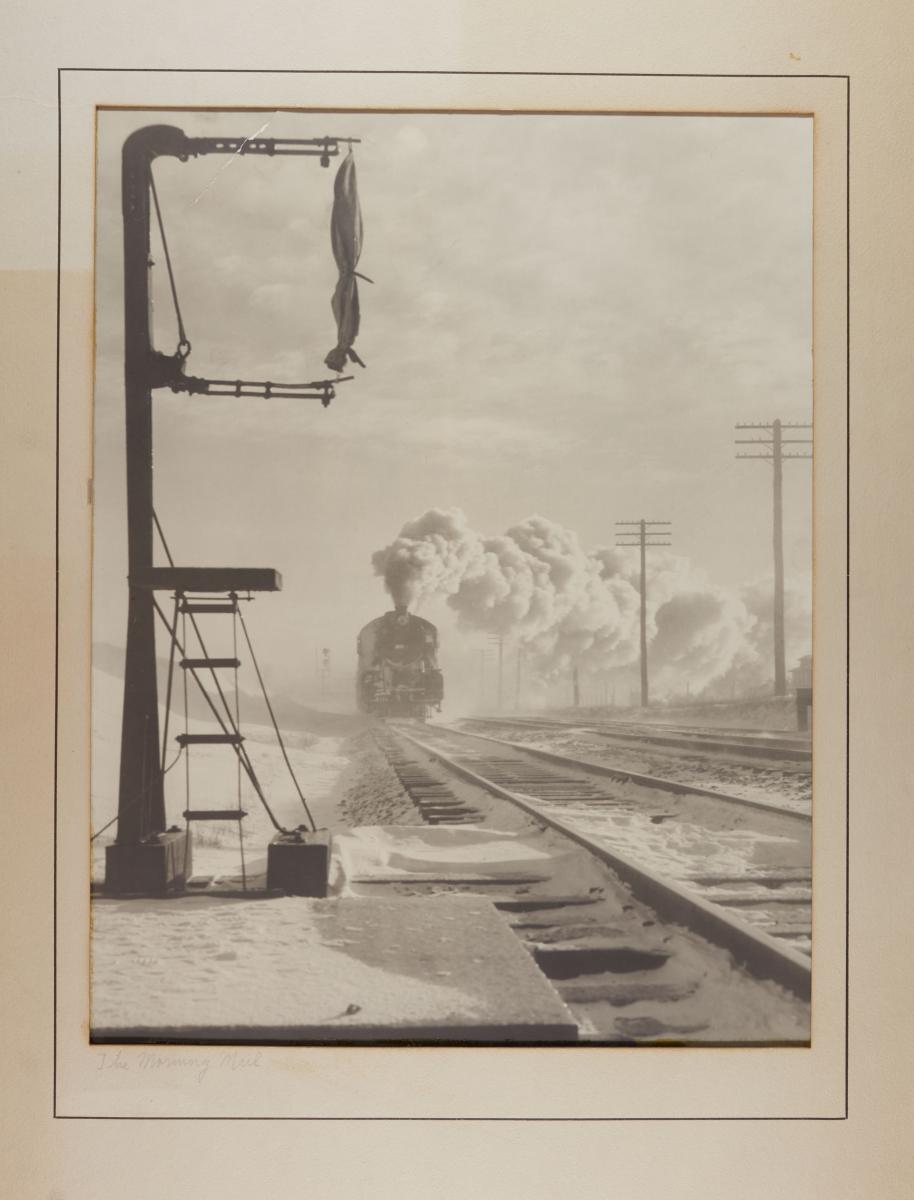

Silver Gelatin Developing-Out

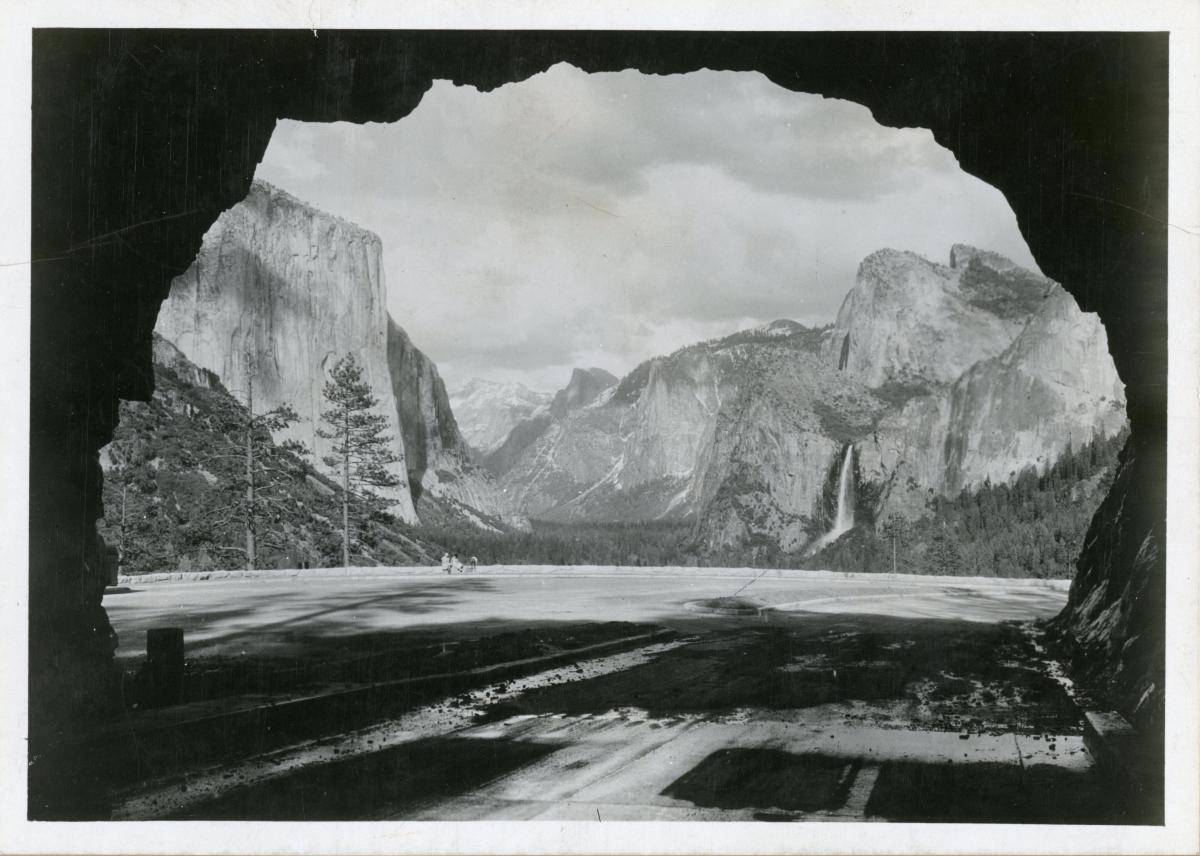

Silver Gelatin Developing-Out Papers (DOPs) made their first appearance in the mid-1880s and became the dominant printing process of the 20th century. Silver gelatin DOP is based on the light sensitivity of silver halides, which are suspended in a gelatin binder on a baryta paper support.

Due to the complexity of the process, silver gelatin papers have always been a manufactured product with a variety of paper thickness, tints, textures, and sheens. Photographic paper manufacturers could vary the thickness of the baryta layer to obscure the paper fibers giving a smooth surface. They also could include matting agents into the emulsion or overcoat, resulting in a matte surface. General aesthetic trends favored matte surfaces in the early 20th century and glossier surfaces toward the mid-20th century.

Untoned prints generally have a neutral black-and-white or warm white image tone that is continuous under low magnification. It is common to see silver gelatin DOP deterioration in the form of silver mirroring in visible areas of high density. This is due to silver oxidation and may also result in fading of the image and a yellow shift in tone.

Subtractive Color Chromogenic Print

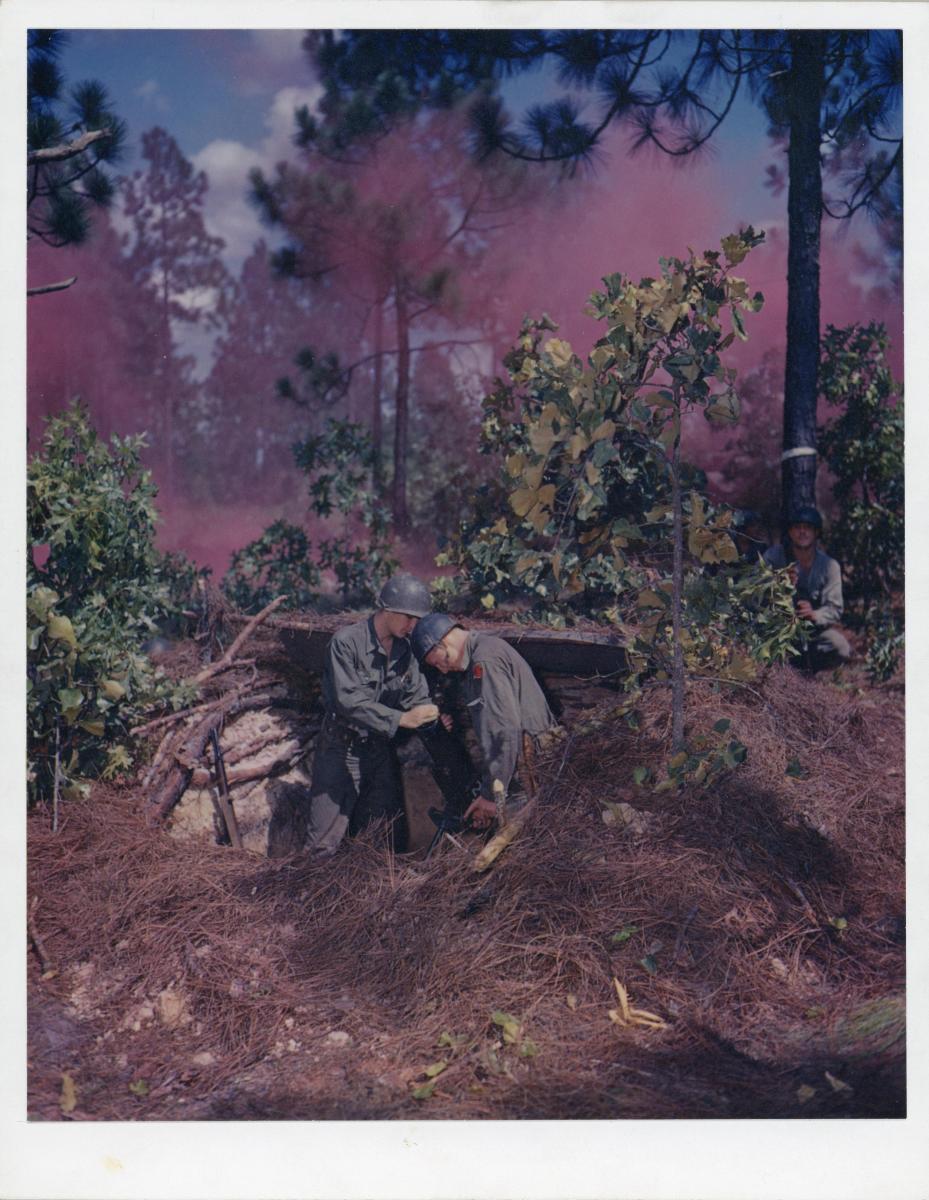

Chromogenic was the dominant color photographic process of the 20th century for prints, negatives, and transparencies. As a subtractive color process, it is based on dye couplers (chemical compounds) reacting with an oxidized developing agent to form cyan, magenta, or yellow dyes where silver is present. Subtractive color prints combine these subtractive colors (cyan, magenta, and yellow) to result in a full color image.

These subtractive dyes or pigments are present in every color print, usually in thin discrete layers. When viewed under magnification, the small cloud of color, otherwise known as dye clouds, can be seen. When first introduced in 1942, these papers had fiber-based supports consisting of a paper support, thick baryta layer, and the emulsion layers. Fiber-based papers would be discontinued shortly after resin coated (RC) color prints were introduced in 1968. RC color prints consist of a paper support sandwiched between polyethylene layers, allowing for faster processing.

Yellow borders and highlights, color shifting, and image fading are common for fiber-based prints made before the 1960s and resin coated prints made in the 1960s and 1970s. Prints that were made in the 1980s and later have little to no shift in color or fading, often showing good dye stability.

Our holdings of color prints are stored in cold storage to prevent/slow down chemical decay and deterioration, due to the dye couplers that are present in the prints. The cold storage differs by about 20 degrees from our cool storage, which is where records such as our black-and-white prints are stored.

Formats

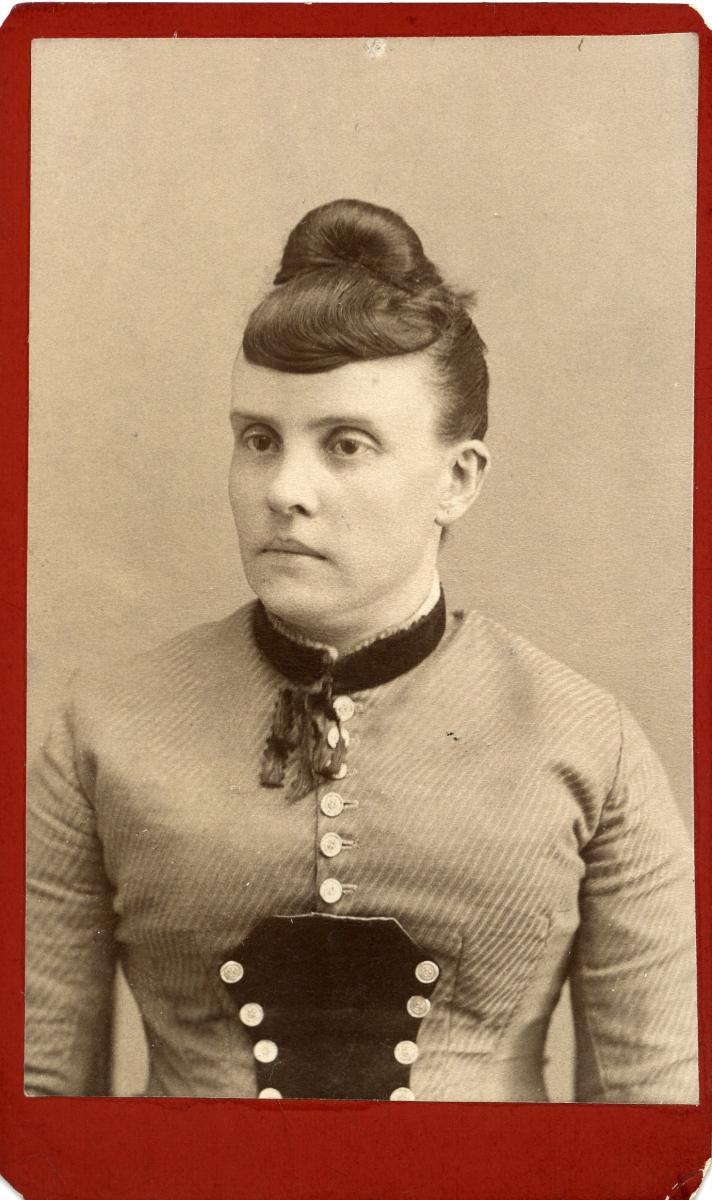

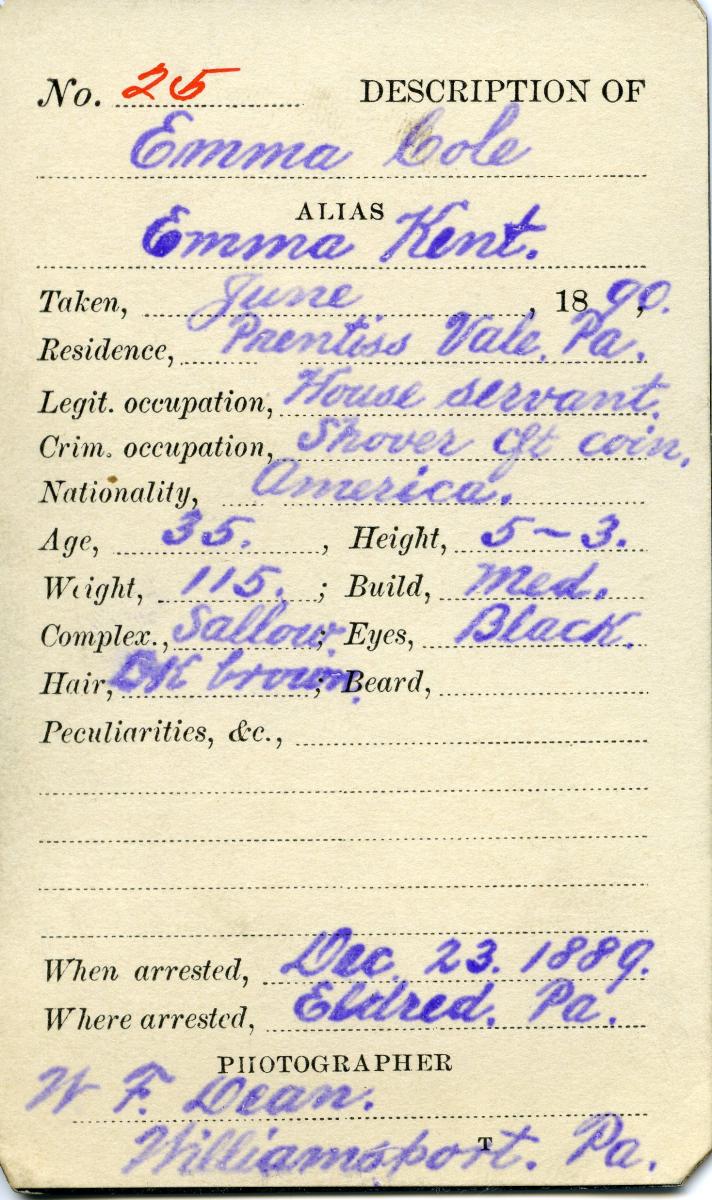

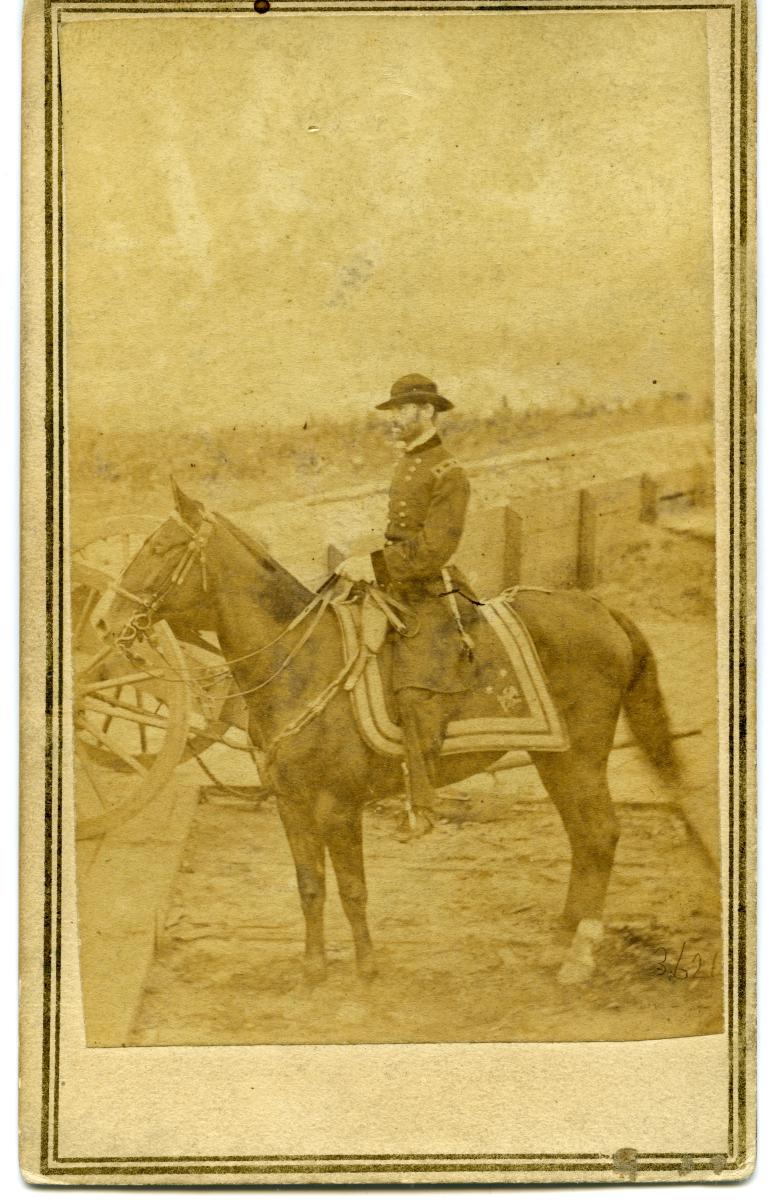

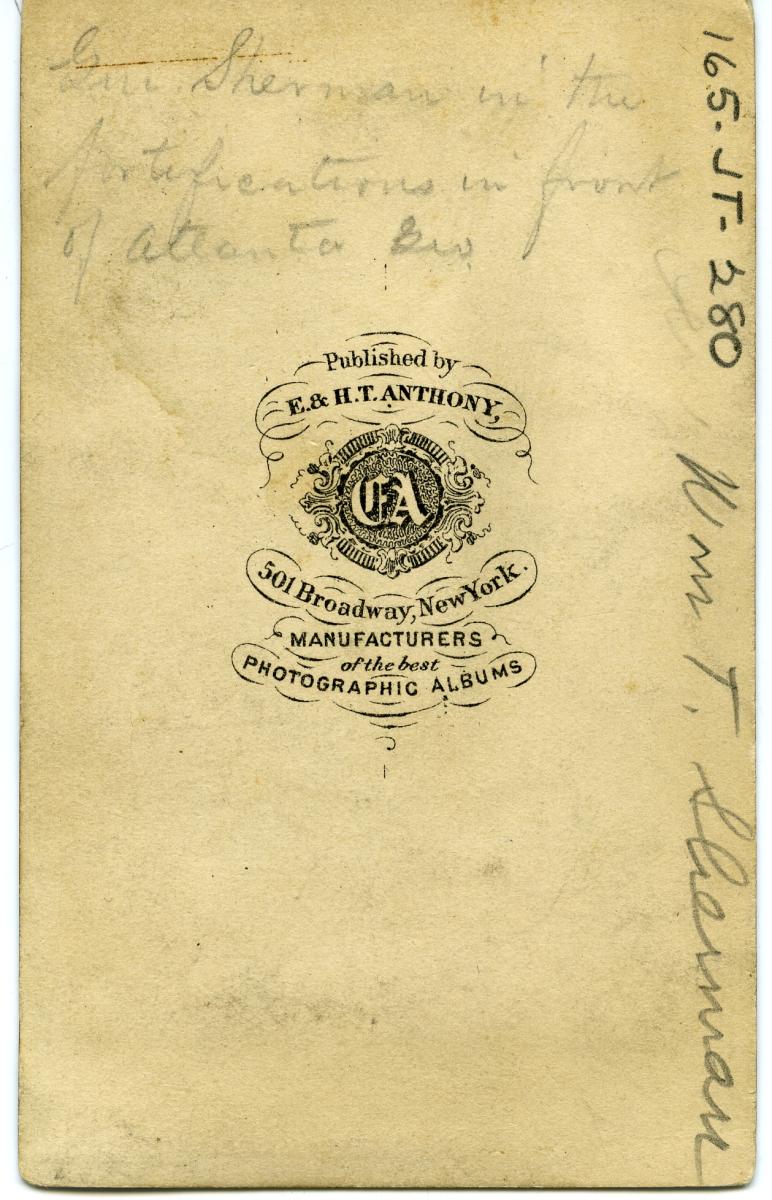

Cartes de Visite and Cabinet Cards

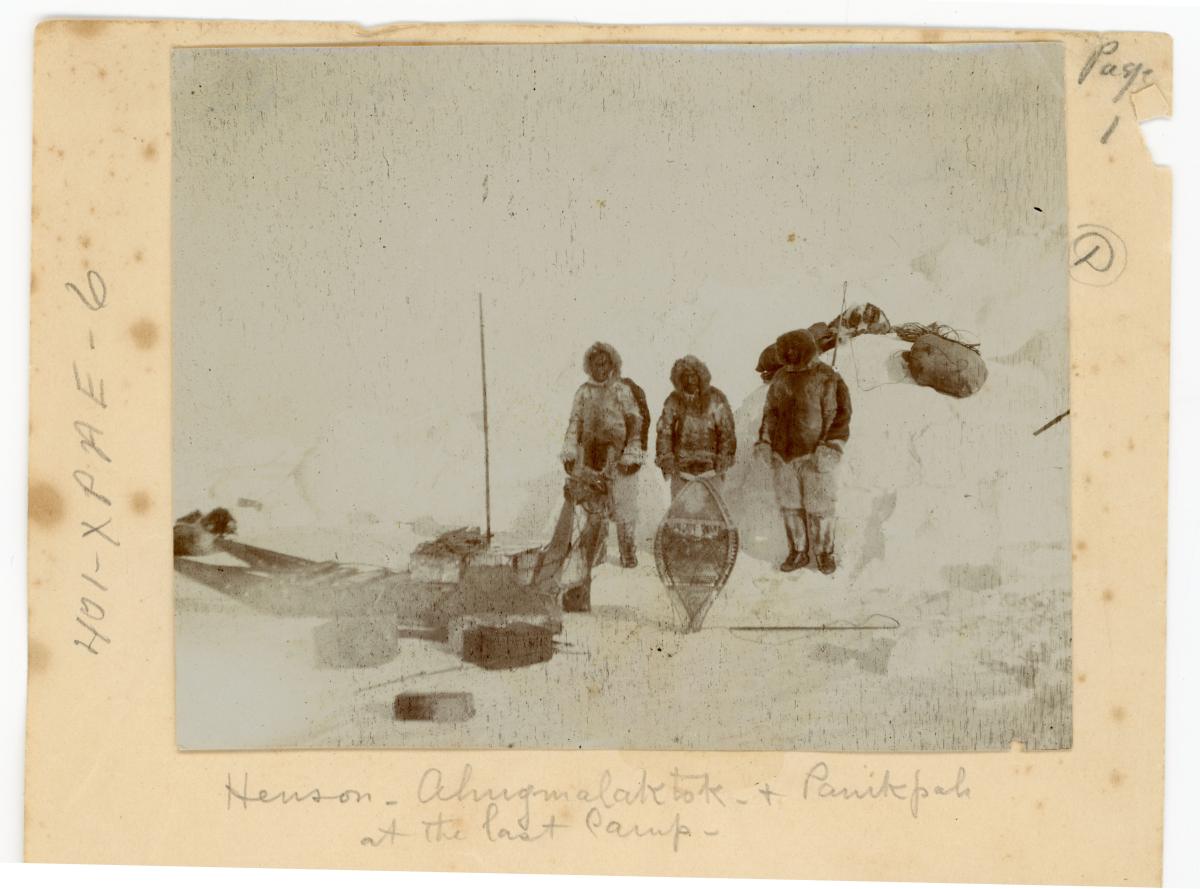

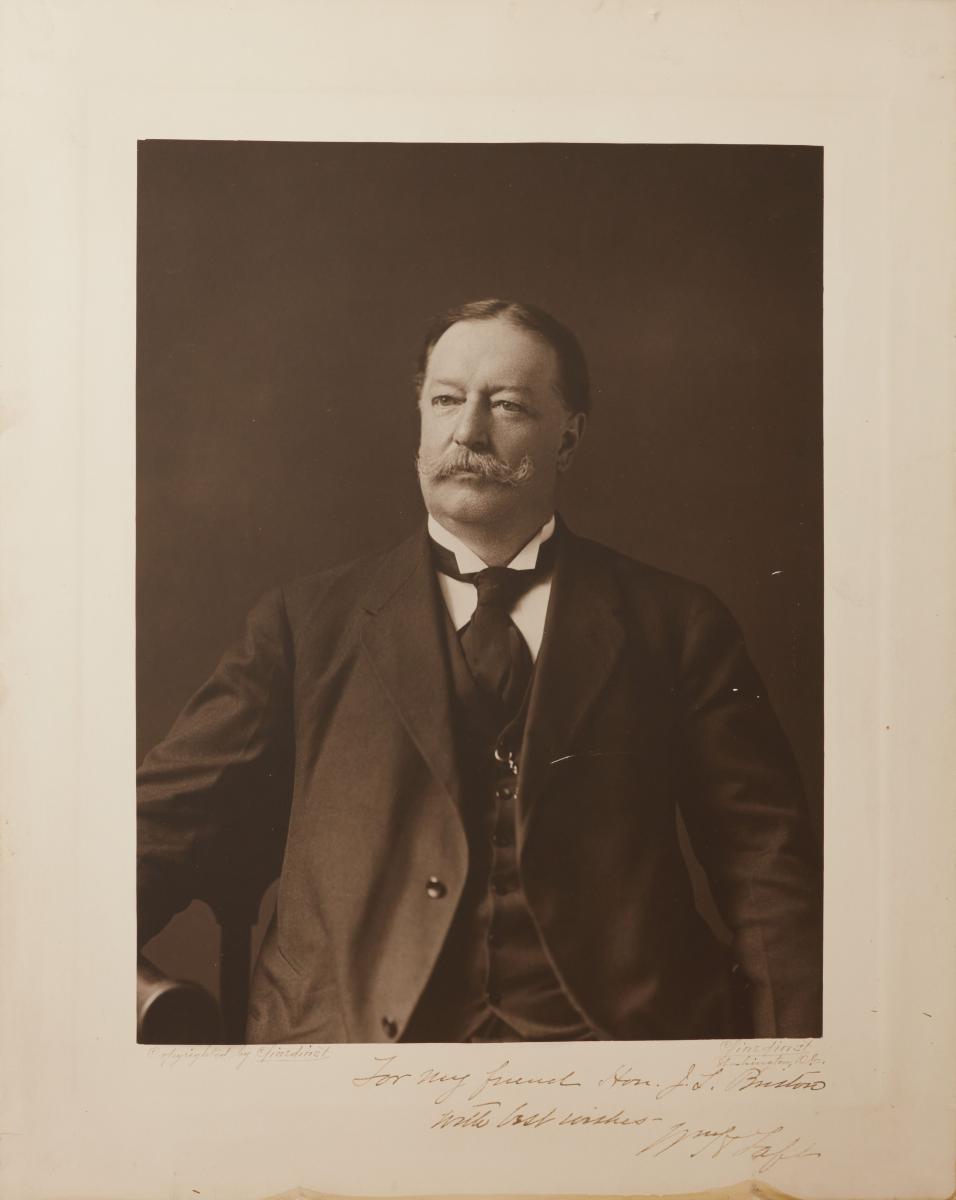

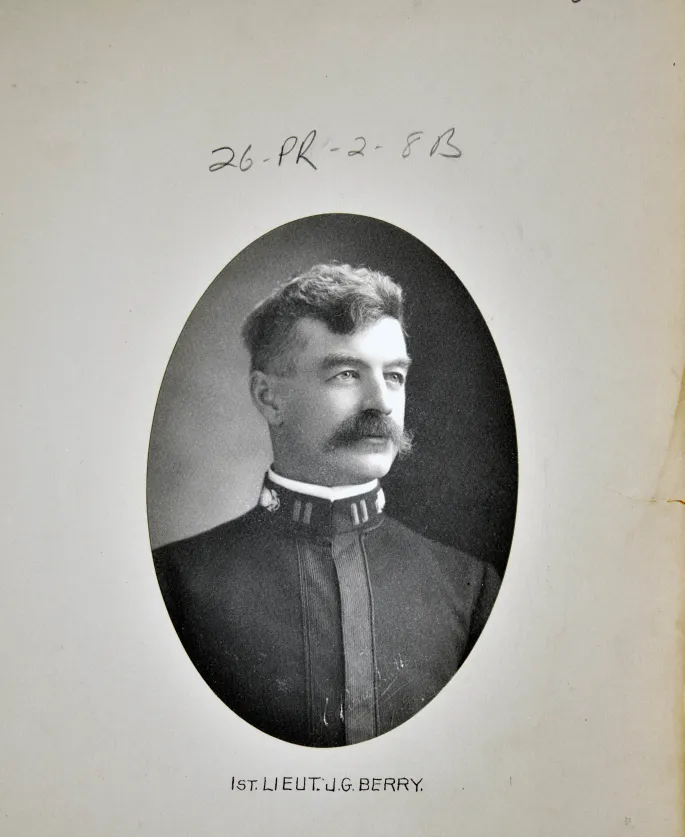

The carte de visite, the most popular format for portrait photography in the 19th century, is a photograph mounted on a thin card measuring approximately 2½ x 4 inches. Named for the French custom of leaving a "visiting card" (or calling card), photographic cartes de visite were usually produced as albumen prints, but most paper print processes could also be used. A special camera with multiple lenses and a movable plate holder was used to make as many images as possible on a single plate. A contact print was then made, and the individual photographs were cut apart and mounted onto cards.

Cabinet cards were introduced shortly after. These were mounted on heavier card stock and measured approximately 6½ x 4¼ inches. The popularity of card photographs as a format continued into the 20th century, and they were often exchanged and collected between friends and family.

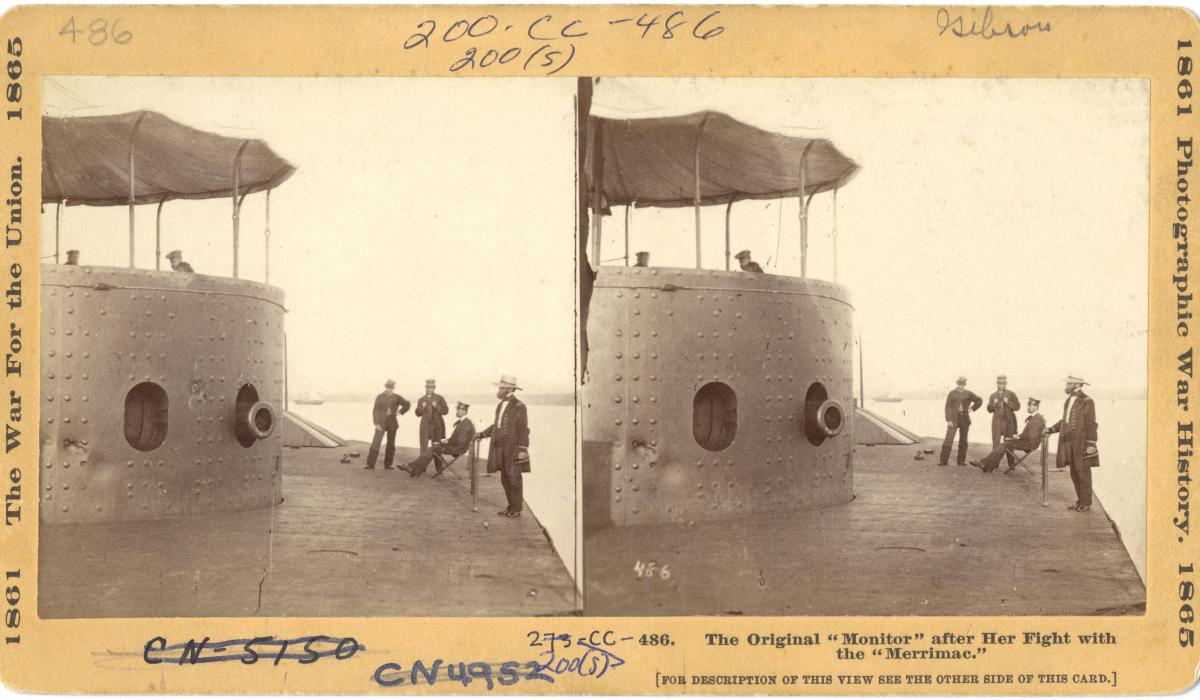

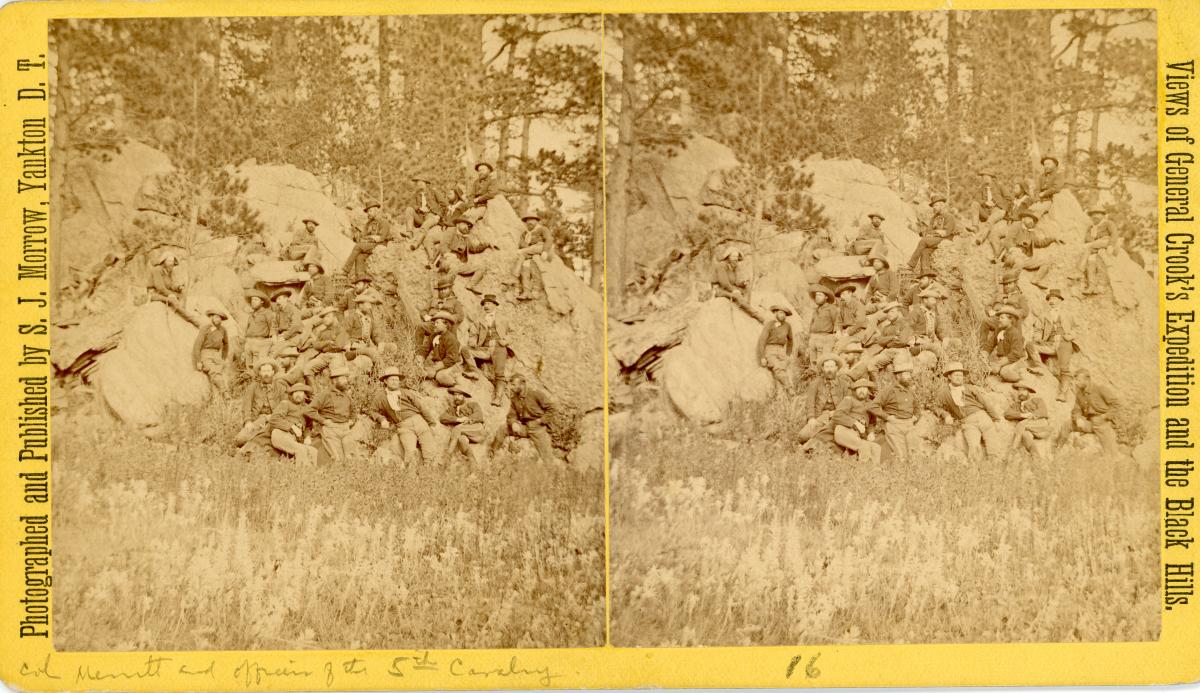

Stereographs

Similar to card photographs, “stereograph” refers to a format, not a technical process. Stereographs are 19th century photographs that are two almost identical photographs, placed side by side, that appear three dimensional when viewed through a stereoscope. These were most commonly produced with cameras that had two lenses side by side, so that two exposures were made simultaneously. Stereographs enjoyed popularity from the late 1860s until after the turn of the 20th century.

Panoramas

Panoramic imagery long pre-dates the invention of photography, but it didn't take long for innovators to begin trying different approaches to creating this type of view using the new and evolving technology. For example, early photographic panoramas were made by assembling two or more daguerreotype plates side by side to create a wide view. By the late 19th century, cameras specifically designed to produce panoramas were being manufactured to rotate the lens so an image could encompass almost 180 degrees.

Advancements in modern technology have evolved panoramic photography significantly, allowing for wider-angle photos, software stitching on multiple images, and longer focal lengths than ever before.

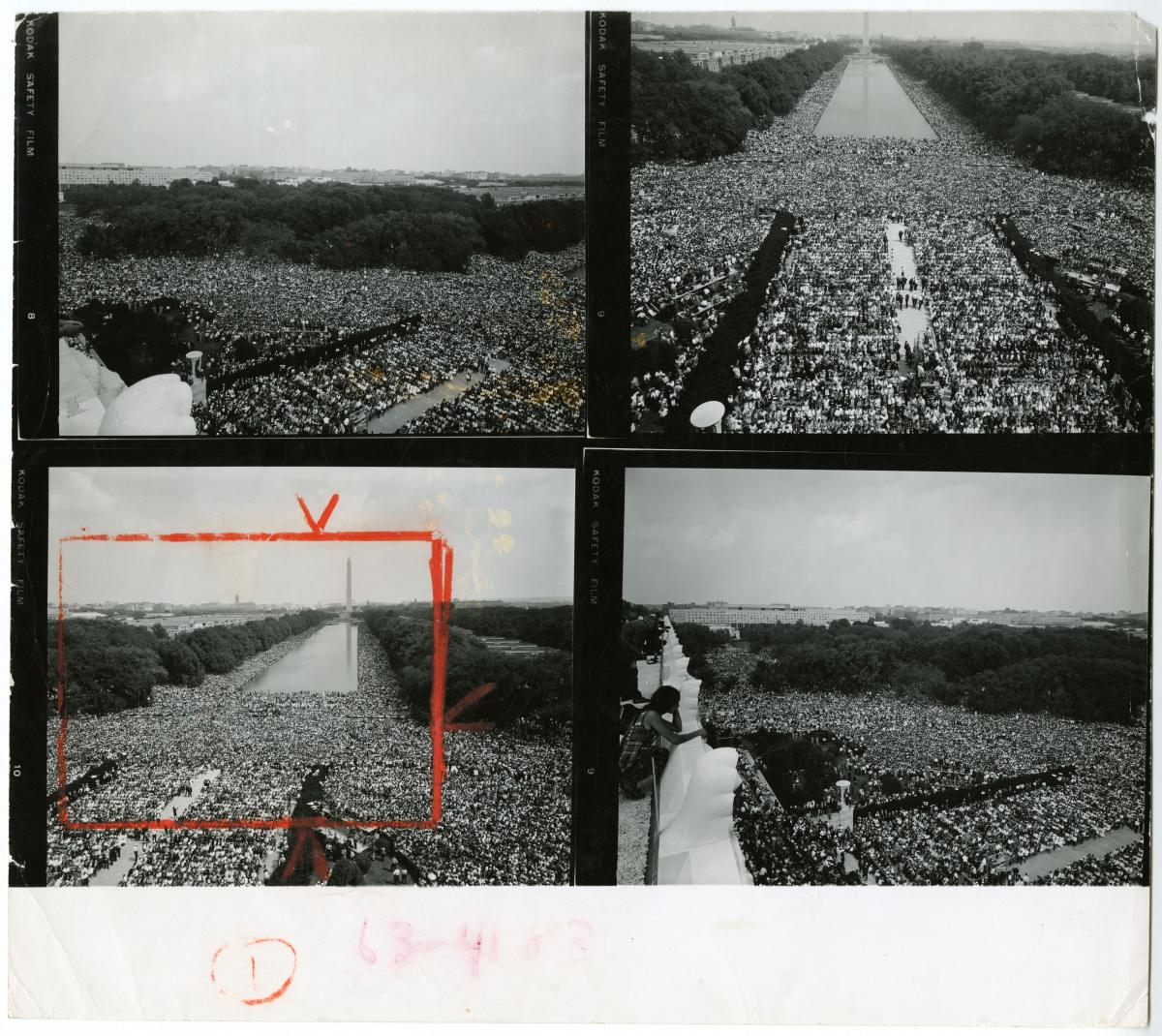

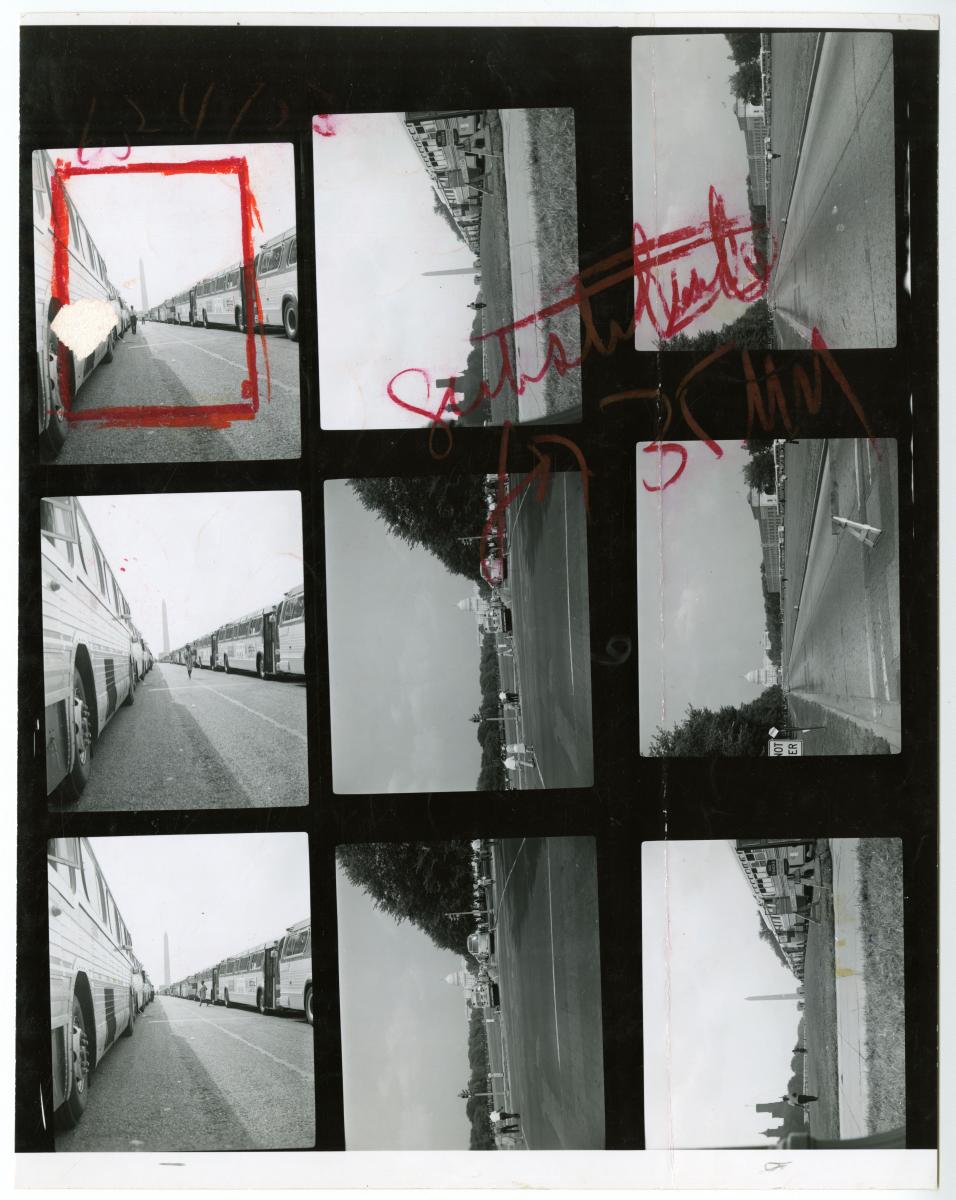

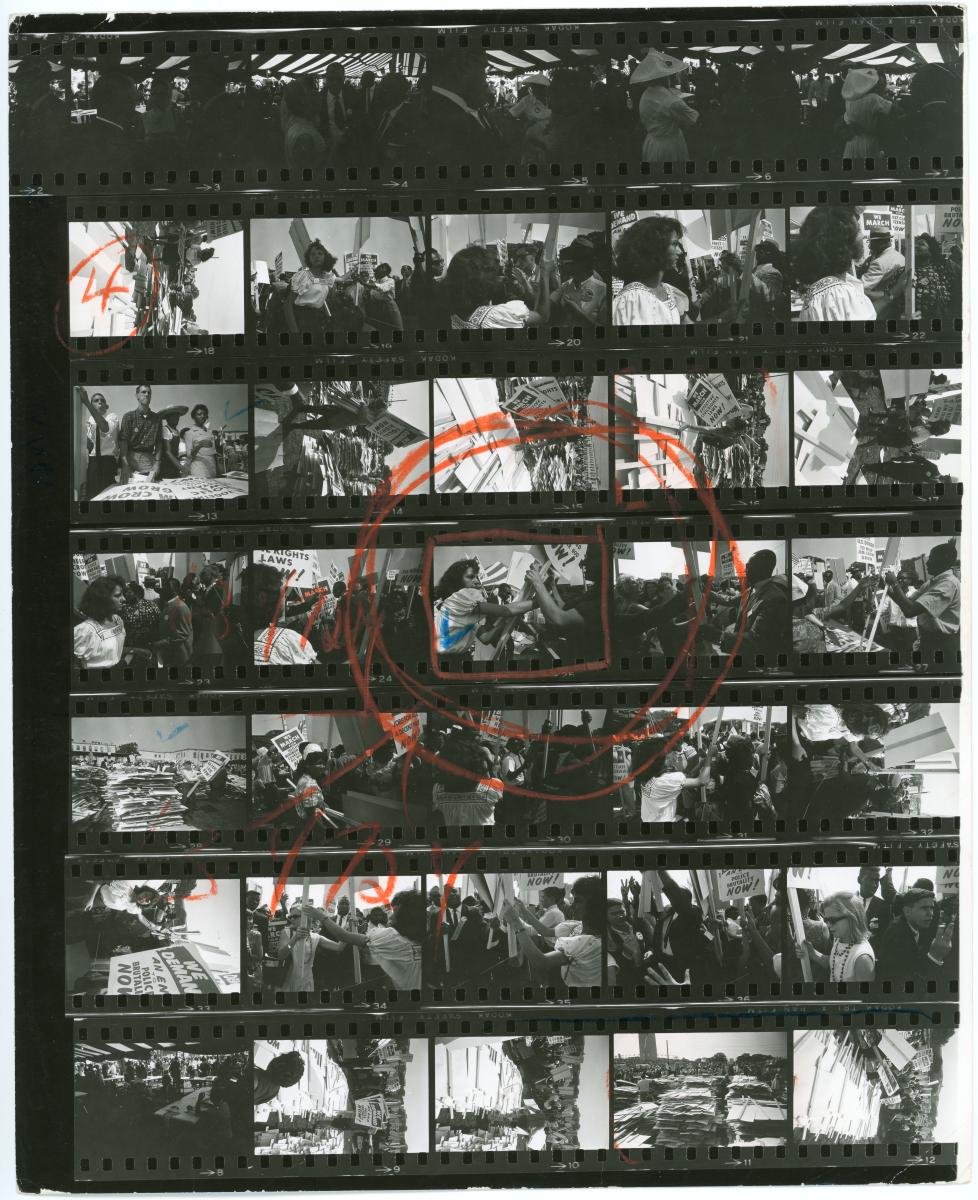

Contact Prints

Contact sheets provided a convenient way to preview all the images on a roll of film at once, optimizing the photographer's workflow and reducing time spent developing unnecessary images. These sheets were a photographer’s first opportunity to see a positive image of each exposure and to choose which frame(s) to enlarge, develop further, or discard. Contact prints also give insight into the photographer's approach to a scene or thought process and vision for the sequence of shots.

Contact Sheets from the series 306-SSM: Miscellaneous Subjects, Staff and Stringer Photographs, , National Archives Identifier: 541992